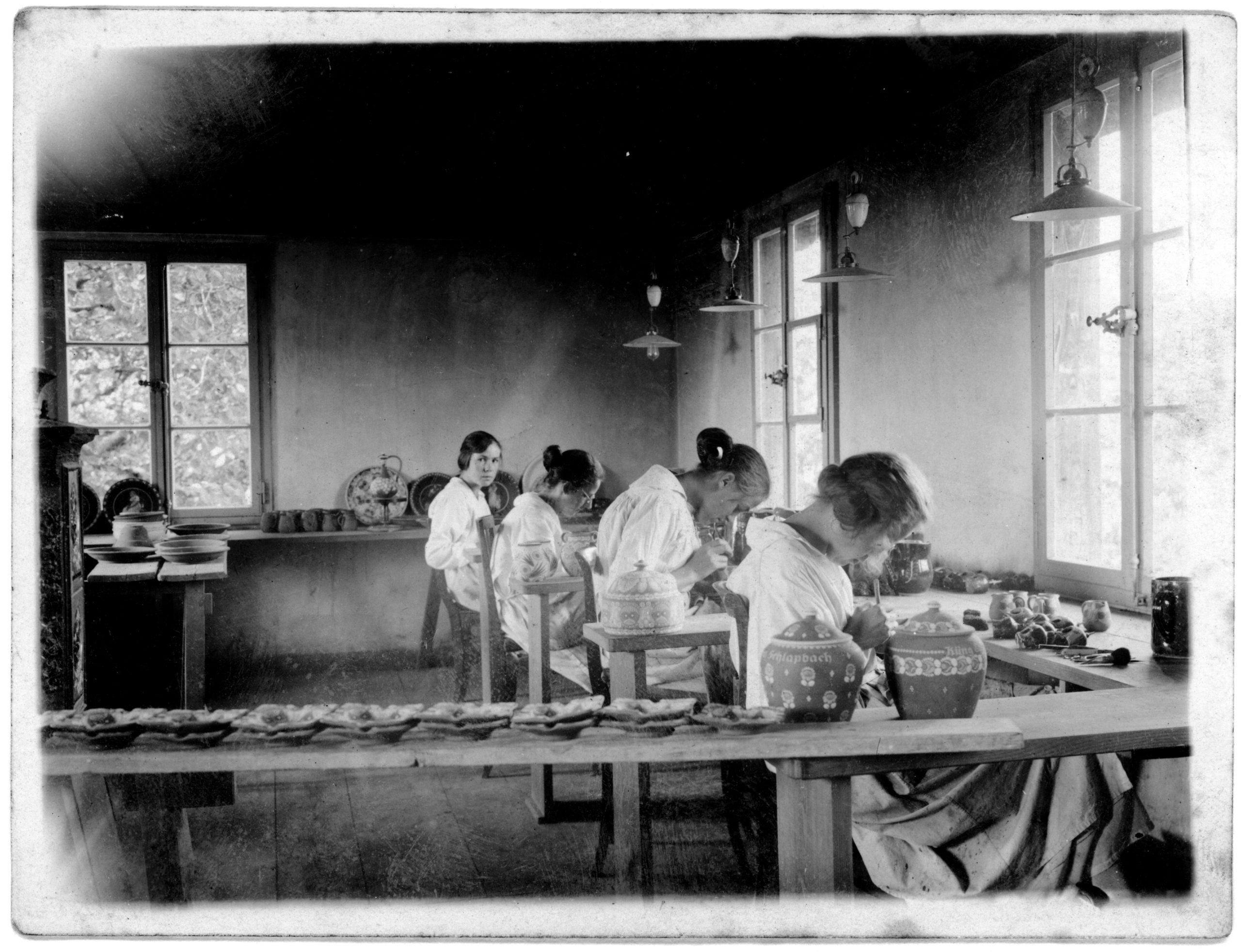

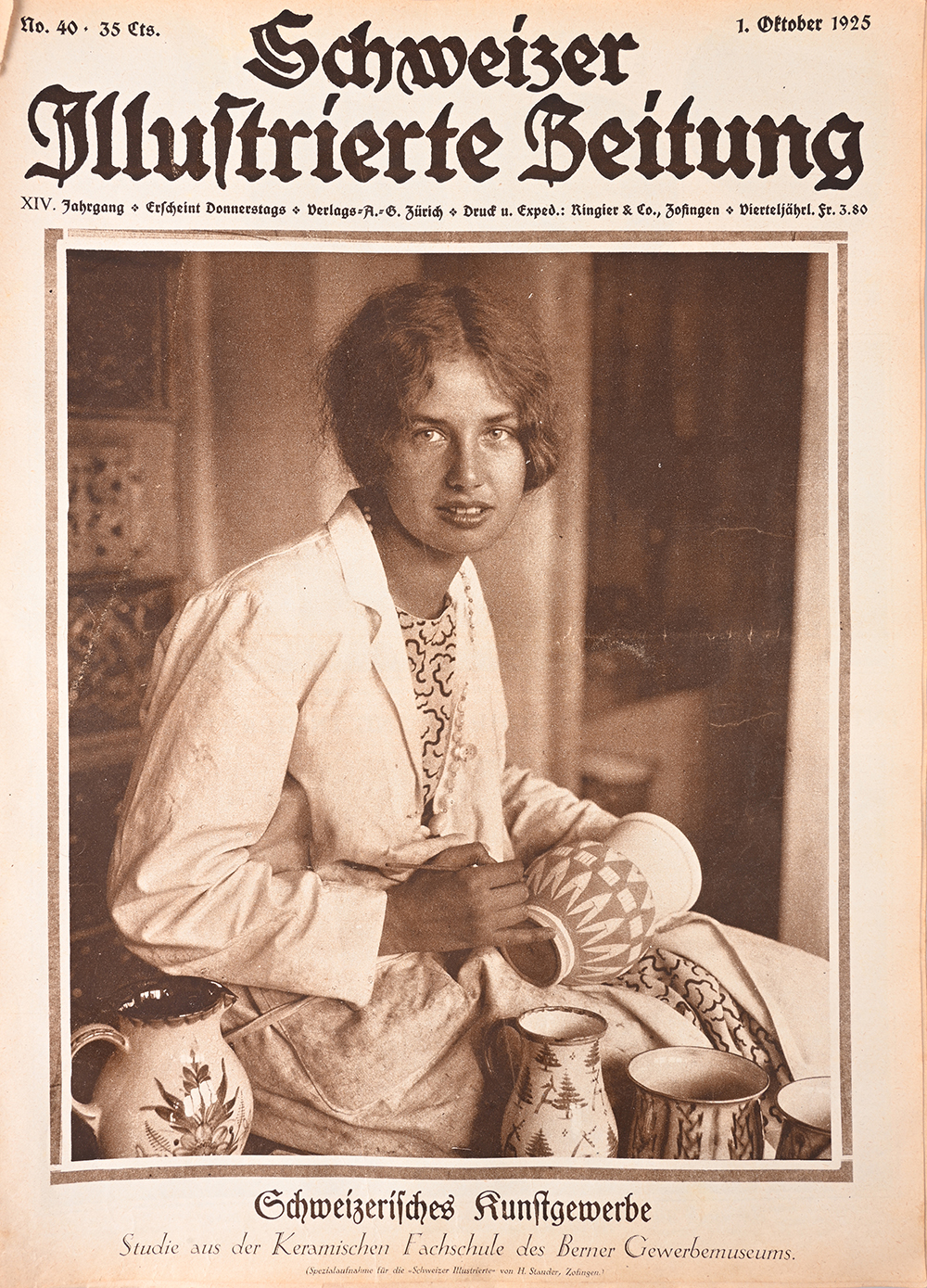

Pottery paintress, Heimberg-Steffisburg 1917 (photographer: Hermann Stauder).

Andreas Heege, Andreas Kistler, 2023

The term “Ausmacherin” can occasionally be found in church records (death registers etc.) in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region and refers to pottery paintresses. It derived from the verb “ausmachen”, which translates as “colouring in/painting”. The term appears to have been restricted to the local area around Heimberg-Steffisburg and does not even feature in the Dictionary of Swiss German.

As we are informed by a source from 1819, these “Ausmacherinnen” or paintresses were employed to decorate “Heimberg-type” pottery. In his 1819 report to the Bernese Economic Commission on a dispute that had arisen in Steffisburg over the installation of a potter’s kiln, Thun District Magistrate Steiger described a typical potter’s workshop. He stated that there were 34 pottery kilns in the parish of Steffisburg at the time. A master potter usually employed one or two journeymen, some also had an apprentice boy and an unskilled worker or handyman. He goes on to say that “Usually, females and children are used for drying the pots, while painting is exclusively undertaken by females.” (StAB B IV 15, Volume XI, 45–46).

Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), Director of the porcelain manufactory in Sèvres from 1800 to 1847, and his seminal 1844 book (source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandre_Brongniart).

In 1836, Alexandre Brongniart, director of the porcelain manufactory in Sèvres, France, visited Heimberg. Eight years later he published a brief description of the local pottery and how it was made. As an eyewitness account by an experienced ceramicist, it is of considerable value (Brongniart 1844, Vol. 2, 14–15):

“The small district of Heimberg, little more than a kilometre from Thun, on the road to Bern, has more than 50 potters. The clay body of their ceramics is composed of two types of clay from the local area: one is reddish and comes from Merlingen [Merligen, to be correct, on Lake Thun; Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 19], the other is from Steffisburg in Heimberg. Before firing, the mixture is a smoky grey in colour; natural earthenware slips or manmade slips dyed using a variety of metal oxides are then applied to colour the vessels. Red ochre is added to produce red vessels, manganese for brown and ferrous white earth is used to make them white. The unfired but well-dried objects are usually coated with these slips, which are then decorated with crude but extremely varied ornaments, using suspensions of clay dyed with adhesive oxides, including antimony, copper, cobalt and also manganese. The colours are put into small containers similar to lamps with quills in the spouts; using these containers, women add coloured dots, lines and other motifs to the vases; the variety of ornaments the potters use to decorate their products in such a simple manner is astonishing. The glaze simply consists of lead minium, which is added in the form of a powder to the unfired but well-dried pieces. The clay body, the coat of slip, the decorative patterns and the glaze are all fired together in a kiln that is shaped like a horizontal cylinder with a sunken firing chamber.”

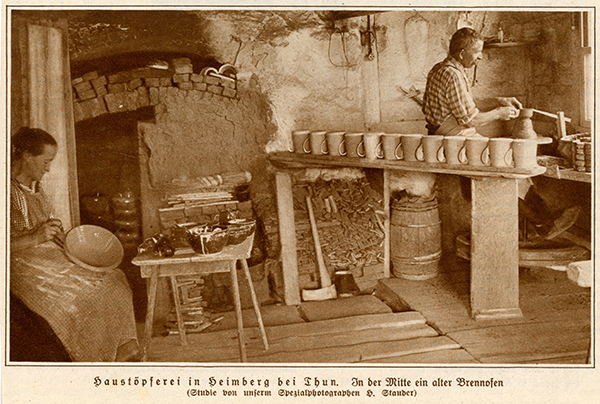

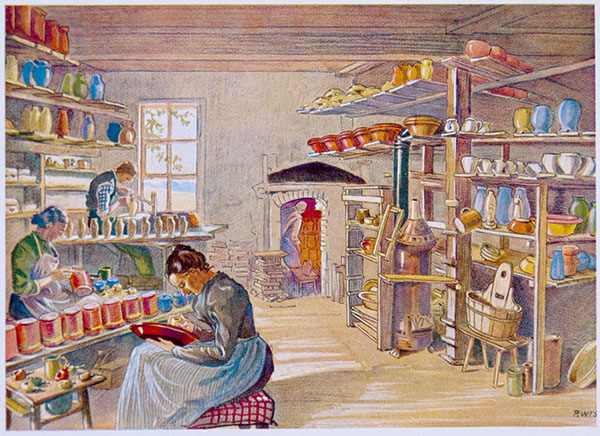

The division of labour that existed in the potters’ workshops of the Heimberg-Steffisburg region between women (paintresses) and men (clay preparation, throwing, loading the kiln and firing the vessels) probably also existed in most other areas of the German-speaking part of Switzerland (though not in Langnau in the Canton of Bern between c. 1700 and 1850). This is supported by various pictorial sources from the early 20th century. While it does not mean that potters (or journeymen) were not capable of doing the painting themselves or never did any of the painting, decorating their products was not usually part of their job.

Heimberg-Steffisburg 1917 (photographer: Hermann Stauder), the classic division of labour.

Loder&Schweizer pottery factory, c. 1920-1924, the paintresses’ workshop (unknown photographer).

Heimberg-Steffisburg 1926 (photographer: Hermann Stauder), the classic division of labour.

Heimberg-Steffisburg 1934 (drawing by Paul Wyss in Wyss 1934), the classic division of labour.

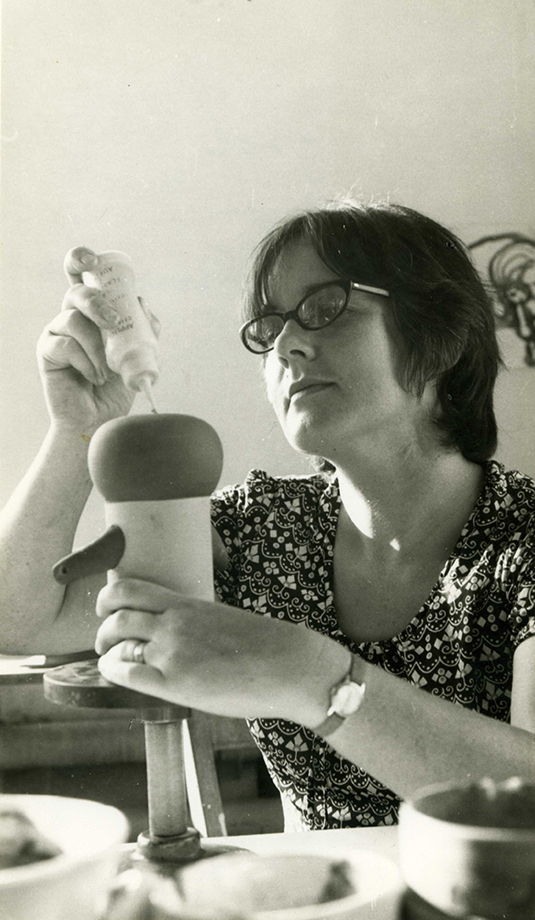

1949, Erna Kohler (later Erna Schröter-Kohler) painting a tureen with incised preparatory lines in the Alt-Langnau style using a slip-trailer. Various brushes and slips for painting or slip-trailing can be seen on the table in front of her (unknown photographer). Erna Kohler attended the pottery college in Bern for a short period of time, but mainly trained in her family’s workshop. The decorating in the Kohler workshops too was mainly done by women.

Influenced by the factory work and the fact that specific training courses were now being offered to pottery paintresses (learning to design and paint their own patterns), for example at the pottery college in Bern, the term “Ausmacherin” and the occupation itself experienced more and more changes. Today, the German word for pottery paintress (“Keramikmalerin”) is more commonly used.

To mark “Swiss Week” in October 1925, the Schweizer Illustrierte newspaper ran a one-page piece on the pottery college and the craft. The front cover had a photo of a pottery paintress.

Both the training and the work itself, however, generally remained segregated by sex until after the Second World War. The occupation of “female potter/ceramicist” (with a complete training course from throwing to firing pottery) was not part of the curriculum initially. This did not change until the mid-1960s.

Margret Loder-Rettenmund (1932– ), trained as a pottery paintress at the pottery college in Bern in the early 1950s; Kunstkeramik A.G. Ebikon, c. 1960 (unknown photographer).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

German: Ausmacherin, Keramikmalerin

French: Finisseuse