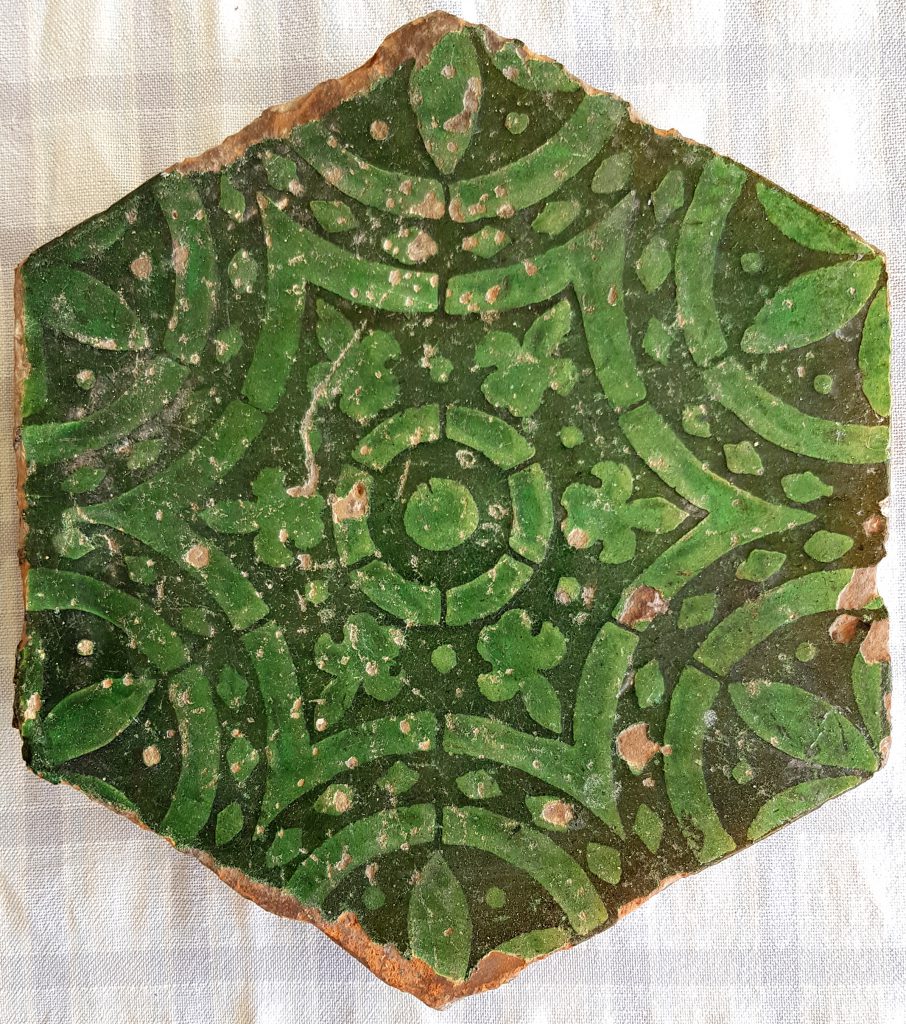

Bowl with stencilled decoration from the infill of the city moat in Bern, Bundesplatz, prior to 1579 (photograph by Andreas Heege, Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern).

Stencilled decoration in CERAMICA CH

Andreas Heege und Eva Roth Heege, 2020

Stencilled decoration on crockery was developed in the German-speaking part of Switzerland in the second half of the 16th century and has been found in relatively modest numbers in archaeological excavations, e.g. in Bern, Zug and Zurich (for more on the topic see: Roth Heege/Thierrin-Michael 2016, 64-66; Frey 2018, 298 and Pl. 1,3). Larger amounts have so far only been recovered from the moat at Hallwil Castle in the Canton of Aargau (Lithberg 1932, Pl. 228-238, 255-257, 278-281; Roth Heege/Thierrin-Michael 2016, Fig. 77; Stephan 1987, 39 Fig. 27).

A bowl and the lid of a box, waster and biscuit-fired piece, both with stencilled decoration from a potter’s workshop at 3/4 Oberaltstadt in Zug, second half of the 16th century (photographs by Res Eichenberger, Amt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Zug).

Evidence of the production of pottery with stencilled decoration has come to light at a potter’s workshop at 3/4 Oberaltstadt in Zug (Roth Heege/Thierrin-Michael 2016, Figs 75 and 76) and at another one in Schaffhausen, at 2 Vordersteig (Bänteli/Bürgin 2017, Figs 306 and 958).

Box with slip-trailed and incised decoration from the Swiss National Museum (HA-3001), Thomann 1962, Fig. 20.

Both sites yielded lids from boxes typical of the period, with stencilled decoration and faience glazing, as did Hallwil Castle (Lithberg 1932, Pl. 255, 281). The Swiss National Museum’s collection also includes a similar, slip-trailed piece bearing the date 1586 (SNM HA-3001; Thomann 1962, Fig. 20). The History Museum in Strasbourg houses a box with slip trailing and stencilled decoration bearing the date 1568, which is the oldest example that has come to light so far (Klein 1989, Pl. 51).

Spice box with slip trailing and stencilled decoration bearing the “pairing number” 43 inside and on its lid. Probably from the Schickler-Pourtalès family, Martinvast Castle near Cherbourg (sold at auction in 2019 by Boscher Enchères, Cherbourg, today in private ownership in Switzerland).

Boxes or objects decorated using this technique are otherwise very rare and almost completely absent from museum collections. A large spice box in a Swiss private collection is the only known exception.

A waster and a biscuit-fired stove tile, both with stencilled decoration from the potter’s workshop at 3/4 Oberaltstadt in Zug, second half of the 16th century (photographs by Res Eichenberger, Amt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Zug).

On stove tiles, however, stencilled decoration became rather widely used from the mid-16th century onwards. Examples have also come to light in Zug (Roth Heege/Thierrin-Michael 2016, 64-66). The earliest pieces with absolute dates known so far are the tiles and plates from the seat of a stove bearing the date 1566 that came from the Rosenburg estate in Stans, Canton of Nidwalden, and are now in the Swiss National Museum (Heege 2012, 92-96, Fig. 12).

Floor tile from the period around 1600 from the Winkelriedhaus in Stans, Canton of Nidwalden, Swiss private ownership.

Floor tiles with similar decorations have been found beneath a tiled stove dated 1577 from Altishofen Castle in the Canton of Lucerne and also covering a floor from the period around 1600 in the Winkelriedhaus in Stans, Canton of Nidwalden (Schnyder 1993).

Stencil and finished stove tile made by Christian Lötscher from St. Antönien, Canton of Graubünden, c. 1840-1850.

The stencils were usually made from parchment, goatskin or oiled paper with cut-out patterns (for a description of the technique dating from 1549 see Boltz 1913). They were placed on the surface of the vessel or tile, which was often coated with slip, and the tile was then covered in a layer of clay that turned a lighter colour when fired. This layer was then covered with a glaze, which could be colourless or coloured (in the case of stove-tiles usually green). After firing, the cut-out pattern was lighter in colour than the areas covered by the stencil. The technique was widely used to decorate stove tiles in Switzerland, south-western Germany and Vorarlberg, Austria, up to the late 20th century (Schatz 2005; Matter 2007; Leib 2013).

Industrial stencilled decoration

In the 19th and 20th centuries, stencilled decoration was also used in the industrial manufacture of faience, refined white earthenware and porcelain.

Plate and metal stencils used to decorate it, Varages, South of France.

From as early as the late 19th century, thin sheet metal stencils were used by almost all European industrial manufacturers of pottery. The coloured patterns were applied either by paintbrush or by air-brushing (on this technique see Gauvin/Becker 2007, 29).

The technique of applying colour using an air-brush and compressed air was patented in the United States of America in 1886 and publicised that same year in an article that appeared in the German journal “Der Sprechsaal”. The porcelain manufactory in Sèvres exhibited air-brushed pieces from as early as the 1889 world exhibition in Paris, and other, German manufacturers followed suit around the turn of the century. By 1910, as many as 93 German manufacturers were using the technique.

Wash jugs and basins with abstract stencilled, air-brushed decoration from the 1920s and 1930s (Klostermuseum Disentis).

Abstract air-brushed, stencilled decoration was only developed between c. 1925 and 1928 and was considered the height of fashion during the period of the Weimar Republic and in the context of Art Deco design (Anthonioz 2019; Figiel 2006).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

German: Schablonendekor, patronierter Dekor, Patronierung

French: décor au pochoir

References:

Anthonioz 2019

Stanislas Anthonioz, À la table de l’art moderne. Céramiques de la République de Weimar (1919-1933), Genf 2019.

Bänteli/Bürgin 2017

Kurt Bänteli/Katharina Bürgin, Schaffhausen im Mittelalter – Baugeschichte 1045-1550 und archäologisch-historischer Stadtkataster des baulichen Erbes 1045-1900 (Schaffhauser Archäologie 11), Schaffhausen 2017.

Blondel 2001

Nicole Blondel, Céramique, vocabulaire technique, Paris 2014, 292.

Boltz 1913

Valentin Boltz, Illuminierbuch. Wie man allerlei Farben bereiten, mischen und auftragen soll, allen jungen angehenden Malern und Illuministen nützlich und fürderlich, durch Valentinum Boltz von Ruffach, Nach der ersten Auflage von 1549 herausgegeben, mit Einleitung und Register versehen von Carl. J. Benzinger (Sammlung maltechnischer Schriften 4), München 1913.

Figiel 2006

Joanna Flawia Figiel, Revolution der Muster. Spritzdekor-Keramik um 1930, Ostfildern-Ruit 2006.

Frey 2018

Jonathan Frey, Alles im grünen Bereich. Die Haushaltskeramik vom Bauschänzli in Zürich, datiert vor 1662, in: AS – Archäologie Schweiz/SAM – Schweizerische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Archäologie des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit/SBV – Schweizerischer Burgenverein, Die Schweiz von 1350 bis 1850 im Spiegel archäologischer Quellen. Akten des Kolloquiums/Actes du Colloque Bern, 25.–26.1.2018, Basel 2018, 297-308.

Gauvin/Becker 2007

Henri Gauvin/Jean-Jacques Becker, Cent ans de faïences populaires peintes à Sarreguemines et à Digoin, Sarreguemines 2007.

Heege 2012

Andreas Heege, Dekortechniken auf Ofenkeramik, in: Eva Roth Heege, Ofenkeramik und Kachelofen. Typologie, Terminologie und Rekonstruktion im deutschsprachigen Raum (CH, D, A, FL) mit einem Glossar in siebzehn Sprachen (Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters 39), Basel 2012, 68-99.

Klein 1989

Georges Klein, Poteries populaires d’Alsace, Strassburg 1989.

Leib 2013

Sarah Leib, Ausgewählte Aspekte der Kachelofenforschung in Tirol und Vorarlberg, in: Harald Siebenmorgen, Blick nach Westen. Keramik in Baden und im Elsass. 45. Internationales Symposium Keramikforschung Badisches Landesmuseum Karlsruhe 24.8.-28.9.2012, Karlsruhe 2013, 191-197.

Lithberg 1932

Nils Lithberg, Schloss Hallwil Bd. 3. Die Funde, Stockholm 1932.

Matter 2007

Annamaria Matter, Dällikon, Mühlestraße 12, Hafnerei Gisler, Kanton Zürich CH, in: Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen-Pottery kilns-Fours de potiers. Die Erforschung frühmittelalterlicher bis neuzeitlicher Töpferöfen (6.-20. Jh.) in Belgien, den Niederlanden, Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (Basler Hefte zur Archäologie 4), 2007, 321-328.

Roth Heege/Thierrin-Michael 2016

Eva Roth Heege/Gisela Thierrin-Michael, Oberaltstadt 3/4, eine Töpferei des 16. Jahrhunderts und die Geschichte der Häuser, in: Eva Roth Heege, Archäologie der Stadt Zug, Band 2 (Kunstgeschichte und Archäologie im Kanton Zug 8.2), Zug 2016, 10-154.

Schatz 2005

Rolf H. Schatz, Südbadische Ofenkeramik des 16. bis 20. Jahrhunderts mit Berücksichtigung der Nordschweiz und des Oberelsass. Bestandskatalog der Sammlung Rolf H. Schatz. Kacheln aus Museen und Privatbesitz, Kachelöfen, Lörrach 2005.

Schnyder 1993

Rudolf Schnyder, Kachelöfen und Fliesenböden, in: Hansjakob Achermann/Heinz Horat, Das Winkelriedhaus. Geschichte. Restaurierung. Museum, Stans 1993, 135-154.

Stephan 1987

Hans-Georg Stephan, Die bemalte Irdenware der Renaissance in Mitteleuropa (Forschungshefte herausgegeben vom Bayerischen Nationalmuseum 12), München 1987.

Thomann 1962

Hans E. Thomann, Die “Roche”-Apotheken-Fayencen-Sammlung, in: Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz Mitteilungsblatt 58/59, 1962, 11-79.