Thin-glazed faience in CERAMICA CH

Jonathan Frey, 2019

Definition, characteristics, manufacture

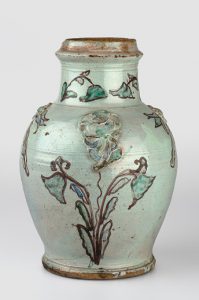

The main difference between thin-glazed and “real” faience is that the glaze is considerably thinner and rilling marks can often be seen under the glaze in thin-glazed ware. Vessels are covered in a white faience glaze, usually either inside or outside, and decorated with in-glaze motifs in manganese purple, green and blue, or more rarely in yellow. The other side is left unglazed or has a greenish lead glaze. In some cases, vessels are covered on both sides in a plain white or sea-green faience glaze. The bases of the vessels are almost always unglazed on the outside.

The fabric of the finely tempered body ranges from light beige-white to pale brick red to bright brick red. Archaeometric analyses have shown that the clay used to produce thin-glazed faience vessels had a lime content of 7 to 20 percent and that the tin content in the glaze was the same as in 18th century thick-glazed faience vessels. Judging by limepops filled with glaze and other macroscopic observations, thin-glazed faience was fired twice; the leather-hard pottery was biscuit-fired, covered in faience and lead glaze, painted and then fired a second time at a maximum temperature of 950°C. From a chemical and technological point of view, thin-glazed faience is therefore on a par with thick-glazed ware. In a few rare cases, i.e. less than one percent of the vessels that have been recorded so far, a white slip can be seen under the faience glaze. These vessels should have been glazed with a lead glaze but were faience-glazed due to a mix up in the workshop after biscuit firing (Frey 2015, 55–56; 241–244; Frey 2019, 71; Heege/Kistler 2017, 107–108; Thierrin-Michael 2015, 313, 324–326).

Vessel shapes

The range of vessel shapes includes jugs, tankards, tureens with cap lids and ledge handles, dishes or bowls with inverted rims and pairs of opposed ledge handles, large bowls with straight-edged rims, large bowls with flanged rims, plates with lips and thickened rims and plates with flat lips. Another group includes flanged and cap lids. Represented only by one example each are apothecary jars, flower vases, double-handled pots, “stegkanne” spouted flagons, wall fountains, wash-bowls, shaving bowls, bowls with handles, puzzle jugs and salt cellars (MAG G37; MAG R225; MAHN AA 1173; MAHN AA 1174; MAHN AA 1570; MAHN AA 1572; MAHN AA 1573; MAHN AA 1574; MAHN AA 1575; MAHN AA 1576; MAHN AA 1577; MAHN AA 1578; MAHN AA 1579; MAHN AA 1580; MAHN AA 1811; MAHN AA 1820; MAHN AA 1827). The shapes of the rims and bases are the same as those on 17th and 18th century lead-glazed earthenware vessels from north-western Switzerland and the Canton of Bern. Typical faience shapes such as lobed platters and other characteristic elements such as footrings, on the other hand, do not occur. From the point of view of vessel shapes, thin-glazed faience was therefore more closely related to lead-glazed earthenware than to traditional faience vessels (Frey 2015, 221; Heege/Kistler 2017, 107).

Glazes, colours and motifs

Tall vessels such as jugs, tankards and flower vases sometimes have applied decorations in the shape of angels, women’s heads, cherubs, flowers, acorns or coats of arms. Known only from archaeological excavations so far are tureens with cap lids, white faience glaze on both sides and opposed ledge handles as well as relief decorations in the form of winged cherubs and, more rarely, palmettes.

Tulips are the most frequently used motifs on jugs, stegkanne spouted flagons and tankards, either in the form of an axisymmetric bunch of tulips or a single tulip with its own stem wound around it like the frame of a medallion. The petals and leaves can be round or pointed, in manganese purple, blue and green, or – very rarely – yellow. The outlines and internal lines in the manganese-green-blue painted motifs are always manganese purple, while in blue painting, both the lines and the shapes are various shades of blue. Besides tulips, there are also rare occurrences of bellflowers, flowers with onion-shaped leaves, garlands of leaves and flowers, birds on branches, and stars.

Tulip medallions and posies are also often found on open forms such as bowls with flanged rims, plates with lips and thickened rims and plates with flat lips, usually as a central motif on the well. Standing tulips with straight stems and symmetrically applied leaves can be found on the wells of these vessel forms. The three different types of tulip are often accompanied on the lip by three tulips with s-shaped stems springing either from the rim or from the edge of the lip. In manganese-blue-green painting the colours of the tulip petals alternate from manganese purple to green to blue. They were obviously intended to depict the variegated and feathered tulips that were so popular in the 17th century. The vessel lips are also decorated with rows of arcs separated by green, narrow, cudgel-like ovals, radial long and narrow petals that together look like the corolla of a sunflower, or star patterns. The smaller lips on bowls with flanged rims are almost always decorated with rows of arcs filled with green or blue semi-circles. The blue-painted vessels can also have purely ornamental motifs such as zigzag or running-dog patterns.

Besides tulips, the wells of plates are decorated with birds on branches, stars and, more rarely, architectural motifs such as churches or castles (Frey 2015, 224–236; Heege/Kistler 2017, 107–108).

The chronology and development of the colours

Thin-glazed faience was first produced shortly after the middle of the 17th century, as attested to by a jug with manganese-green-blue-yellow painting from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, which is dated 1657 (FWMC C.2966-1928). A jug from the Musée Ariana dated 1663 and archaeological finds from Rötteln Castle in Lörrach near Basel, which was destroyed by fire in 1678, date from slightly later.

Judging by a plate dated 1669 from the Blumenstein Museum in Solothurn (MBS 1905.174) and archaeological finds from Court, Sous les Roches (1673–1699), Solothurn, Palais Besenval (pre 1705), Court, Pâturage de l’Envers (1699–1714) and Solothurn, Stadttheater (pre 1729), thin-glazed faience was widely available in the area around Solothurn in the final quarter of the 18th century at the latest. At Court, Sous les Roches, thin-glazed faience vessels made up 13% of the tableware, while at Solothurn, Stadttheater they accounted for 16%. At the glassworks of Court, Pâturage de l’Envers in the first decade of the 18th century, thin-glazed faience accounted for a quarter of all vessels. Thin-glazed faience was therefore the predominant type of prestigious tableware in the greater Solothurn region at the time. The assemblage from Burgdorf, Kornhaus (pre 1715) in the Bernese midlands, on the other hand, only contained a few fragments of blue painted thin-glazed faience, and while it was completely absent from Burgdorf, Kronenplatz (pre 1734), thin-glazed faience in the assemblage from Bern, Waisenhausplatz (circa 1700-1740) made up only 0.5 % of the pottery. Because there are no vessels with exact dates in museums from after 1730, except for one plate bearing the date of 1750 in the museum of Laufen, Canton of Basel-Land, we can say that production of thin-glazed faience appears to have gradually declined from the 1730s onwards. It is probably no coincidence that it was during that particular decade that several new faience workshops opened up in Germany, France and elsewhere in Switzerland, which would have competed against local manufacturers of thin-glazed faience.

The vessels with dates and the assemblages of firmly dated archaeological finds from Court, Sous les Roches (1673-1699), Solothurn, Palais Besenval (pre 1705), Court, Pâturage de l’Envers (1699–1714) and Solothurn, Stadttheater (pre 1729) all show that manganese-green-blue painted vessels dominated until around 1700. Yellow was only rarely used and had fallen out of favour completely by the first quarter of the 18th century at the latest.

The first blue-painted thin-glazed faience vessels, on the other hand, began to appear just before 1700, as attested to by archaeological finds from Court, Sous les Roches and a jug dated 1699 from the Burgdorf Castle Museum. During the first third of the 18th century, the blue-painted vessels gradually replaced those with manganese-green-blue motifs, as the finds from Court, Pâturage de l’Envers clearly show. However, the fact that the assemblages from Burgdorf, Kornhaus (pre 1715) and Burgdorf, Kronenplatz (pre 1734) only yielded thin-glazed faience vessels with blue painting was probably due both to the chronology and to regional preferences (Frey 2015, 244–248).

Besides vessels with manganese-green-blue painting, undecorated tureens with cap lids and white glaze on both sides were also found at the glassworks of Court, Sous les Roches. Similar vessels were also used at the glassworks of Court, Pâturage de l’Envers. This type of tableware is probably only absent from museum inventories because it was not painted and therefore bore no date. The glassworks of Court, Sous les Roches yielded one sea-green thin-glazed faience bowl with an inturned rim. Several other pieces were found at the glassworks of Court, Pâturage de l’Envers and in a latrine beneath the city theatre of Solothurn. The fact that sea-green thin-glazed faience was produced is noteworthy because sea-green faience was made in France as early as the 1630s to imitate highly prized celadon ware from Asia.

Area of distribution and development over time

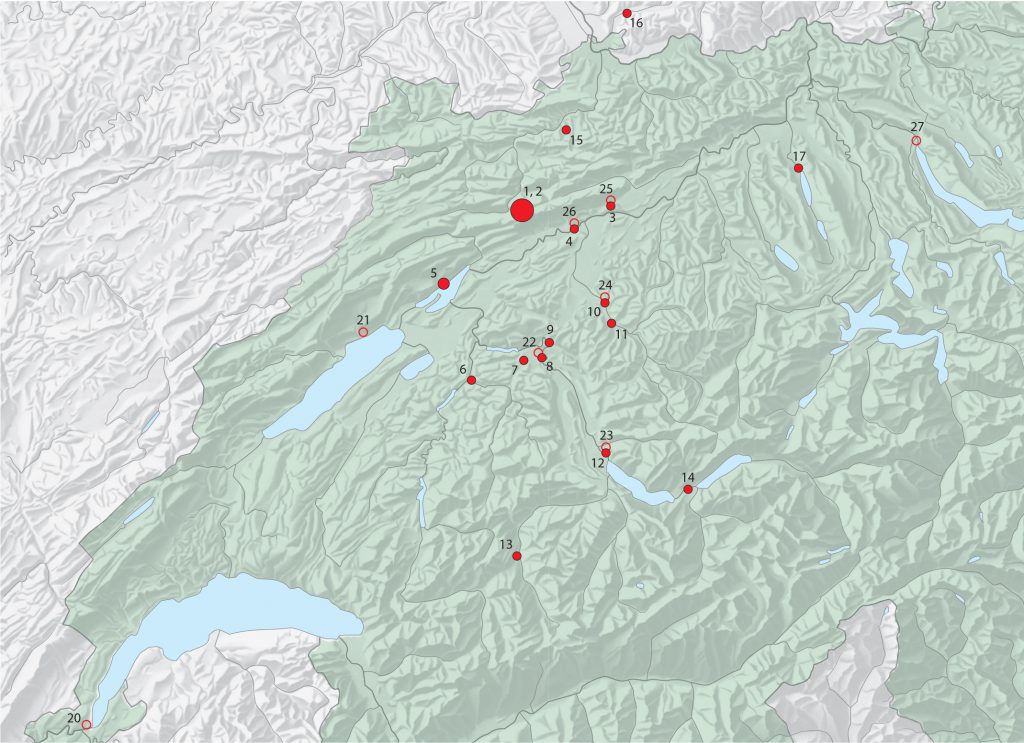

Thin-glazed faience has been found at various sites in the southern Jura region, at the southern foot of the Jura Mountains, in the Bernese midlands and Oberland regions and some pieces have also come to light in the Canton of Aargau and in the Basel region (solid dots).

(For a list of the sites on the map see Frey 2015, Figs. 189 and 217, state of research 2015)

The area of distribution of the museum pieces (empty dots) is larger but confirms that of the archaeological finds in that it encompasses them. The archaeological finds are distributed across a far greater area than the trading areas of most 18th century workshops, which rarely exceeded 30 kilometres or a day’s journey on foot. This means that thin-glazed faience must have been produced by several workshops, which may have been in operation simultaneously. A plate dated 1664 from the Blumenstein Museum and archaeological finds from Court, Sous les Roches (1673–1699), Solothurn, Palais Besenval (pre 1705), Court, Pâturage de l’Envers (1699–1714) and Solothurn, Stadttheater (pre 1729) point to Solothurn as a possible place of production. This is consistent with the fact that the Wysswald workshop known from written sources to have existed from no later than 1697 in Solothurn began to produce high-quality faience from 1734 at the latest. A plate with blue painting made in 1726 by potter Christen von Allmen possibly for his own use (BHM 20778) attests to the fact that thin-glazed faience was also produced in the Bernese Oberland from no later than the first third of the 18th century. However, further discoveries of potters’ waste will have to be made before we can firmly identify the manufacturers of thin-glazed faience in Switzerland (Frey 2015, 248; Heege/Kistler 2017, 107).

Tulip mania in the Baroque period

Native to Central Asia, the tulip came to Europe in the first half of the 16th century, where it quickly spread to all major capital cities thanks to the busy exchange networks maintained by botanists. By the second half of the century, wealthy city dwellers had already begun to enrich their ostentatious gardens with these new flowers. Specially designed tulip gardens became status symbols for an upper class that hired specialist flower painters to record their gardens in books. Particularly popular were tulips with petals that had two-tone patterns in flame-shaped lines. Known as flames or feathering, these variegated colours were particularly interesting because their occurrence was unpredictable and tulip growers never managed to reproduce them. As a consequence, the price of certain varieties of tulip bulbs in the Netherlands rose to exorbitant levels during the first third of the 17th century and led to the first speculative bubble ever recorded. Although the bubble eventually burst in 1637, the tulip’s popularity never waned, and those who could not afford the flowers themselves bought paintings of tulips at least. An even cheaper commodity were everyday items decorated with tulips, which is why tulip ornaments can be found on Dutch ceramic tiles, Bern pulpits and prestigious pewter vessels from no later than the mid-17th century onwards. Unsurprisingly, tulips as decorative motifs on prestigious tableware were soon adopted by local potters too, who used them to decorate their thin-glazed faience vessels (Frey 2015, 236–240).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

German: Dünnglasierte Fayence

French: Faïence à revêtement mince

References:

Frey 2015

Jonathan Frey, Court, Pâturage de l’Envers. Une verrerie forestière jurassienne du début du 18e siècle. Band 3: Die Kühl- und Haushaltskeramik, Bern 2015.

Frey 2019

Jonathan Frey, Die Haushaltskeramik aus der Latrine unter dem Stadttheater von Solothurn, datiert vor 1729, in: Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Kanton Solothurn 24, 2019, 55-76.

Heege/Kistler 2017

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Poteries décorées de Suisse alémanique, 17e-19e siècles – Collections du Musée Ariana, Genève – Keramik der Deutschschweiz, 17.-19. Jahrhundert – Die Sammlung des Musée Ariana, Genf, Mailand 2017.

Thierrin-Michael 2015

Gisela Thierrin-Michael, Archäometrische Untersuchung ausgewählter Grosswarenarten, in: Jonathan Frey, Court, Pâturage de l’Envers. Une verrerie forestière jurassienne du début du 18e siècle. Band 3: Die Kühl- und Haushaltskeramik, Bern 2015, 299–326.