“Heimberg-type” pottery in the image database

Determining the origin of “Heimberg-type” pottery

or

Did all “Heimberg-type” pottery originate from Heimberg/Steffisburg in the Canton of Bern?

Andreas Heege, 2019

The range of pottery shapes and decorations in the German-speaking part of Switzerland from the late 18th to the 20th century with coats of black, white or red slip and slip-trailing, incised motifs and chattered decoration, e.g. from Hohenklingen Castle near Stein am Rhein in the Canton of Schaffhausen, from the Cantons of Graubünden and St. Gallen and from the Austrian State of Vorarlberg suggest that there must have been at least one, if not several other centres of production for wares decorated in the “Heimberg style”. The question of whether this was in fact Berneck in the Canton of St. Gallen, Steckborn in the Canton of Thurgau or perhaps the Hanhart pottery factory (1878-1887) in Winterthur (Schnyder/Felber/Keller et al. 1997, 38: “Malen auf Ton nach Heimberger Manier”, Frascoli 2004, Pl. 34-38), or whether there was an influx of wares into eastern Switzerland from Kandern in the Black Forest of Germany or from Lustenau in Vorarlberg, Austria, cannot be ascertained, due on the one hand to a lack of scientific analyses and on the other to the fact that there are not enough vessels that can be linked beyond doubt to these areas. In any case, the Historical Museum of St. Gallen simply assigns its numerous tureens to producers in Berneck in the St. Gallen Rhine Valley, where the pottery industry can be traced back to the 17th century. In the 19th century, up to 17 workshops operated in Berneck and in the neighbouring parishes or districts of Au, Balgach, Altstätten, Eichberg, Lüchingen and Marbach.

In 1921, 1955 and 1975, various authors attributed the typological links between Berneck and Heimberg/Steffisburg to “Heimberg women” marrying potters from Berneck, although neither Fernand Schwab nor Leo Broder nor Hermann Buchs provided any genealogical evidence for their assertions. The fact that from as early as 1819 and 1836, the women in Heimberg generally worked as pottery paintresses could perhaps explain the close typological and decorative similarities between Heimberg/Steffisburg and Berneck, which had existed since the first third of the 19th century. The argument does not hold up, however. A survey of the origins of the spouses of known 19th century Berneck potters in the church registers did not uncover any such intermarriages. Leondus Federer, a Catholic potter from Berneck, was the only person for whom the Steffisburg church registers showed that he had moved to Heimberg in 1819. However, he later returned to Berneck. The Berneck potter Franz Joseph Kurer acted as godfather to a boy born in Steffisburg in 1824. If the stylistic similarities were not due to the presence in Berneck of pottery-painting wives from Heimberg, the only other possible explanation would be that travelling journeymen transferred their typological and stylistic knowledge from one place to the other. Between Joseph Anton Kurer, the first journeyman whom we can identify in the region of Heimberg in 1832 and Joseph Anton Ritz, the last one in 1879, another 18 journeymen from Berneck and its surroundings can be found in the Bernese registry of foreign citizens. Several journeymen from Berneck worked in the region of Heimberg for one or two years.

A chance find sheds further light on “Heimberg-type” pottery. A typical shallow bowl with a coat of black slip and a bevelled rim in the collection of the Swiss National Museum (SNM LM-72744) bears an inscription that reads “This bowl was made from earth and if it breaks, the potter laughs. Ch. Dürringer, potter”. Interestingly, the bowl also bears the inscription “Steckborn, Canton of Thurgau”.

Besides earlier fundamental research by Karl Frei, the potters from Steckborn were also the subject of a more comprehensive study by Margrit Früh, which included genealogical information, but which focused on tiled stoves and stove fitters. We know very little about how much crockery the Steckborn potters produced or what shapes they preferred to create. The works of pottery painter Georg Hausmann (possibly 13/8/1826–13/8/1882), who may have worked as a journeyman for Christoph Düringer (1794–1851), are the only ones to have found their way into museum collections or to have been mentioned in the literature because his wall-mounted plates bore political motifs from the period of the Freischarenzüge (1845) [military campaigns by Swiss volunteer detachments], which are of cultural and historical interest. Hausmann is known to have spent some time in Heimberg, at least in 1846.

Karl Frei related information given to him by potter August Düringer (1841–1928) with respect to the middle of the 19th century. According to Düringer, Steckborn potters produced milk jugs, coffee bowls, sugar boxes, soup bowls, rounded bowls, shallow dishes, flowerpots as well as cider and wine jugs. The vessels were covered in coats of red, white or black slip and then decorated with slip-trailed motifs (dots, spirals and floral patterns). Using the same method as the Heimberg potters, they were then covered in a powdered lead-glaze. The reference to black slip is particularly noteworthy, as this seems to attest to important typological and stylistic links or similarities between the regions of Lake Constance and Bern, which can also be seen in the dish made by potter Christoph Düringer mentioned above.

The similarities become more obvious and natural when we look at the activities and sales of various Steckborn potters in Heimberg and Steffisburg. They include Hans Jakob Düringer II (1775–1841), who married Anna Mühlemann (1775–1848) from Lotzwil in the Canton of Bern in 1806. He worked in Heimberg and was buried in Steffisburg on 6th April 1841. His wife died seven years later. In 1813, his brother, Hans Conrad Düringer (1791–1849, teacher and stove painter), is known to have traded in Bernese crockery (made by his brother?). Between 1850 and 1855, the two potters David and Johann Heinrich Baldin (1817–1855 and 1829–1876 respectively) worked for potters in Oppligen and Heimberg. As mentioned above, the potter August Düringer (1841–1928) worked as a journeyman for the Heimberg potters Jenny and Knecht and the Steckborn potter Conrad Schiegg in 1861. According to the journeymen’s lists, Schiegg had a workshop adjacent to the Rotachen Bridge in Opplingen from 1849 to 1854 and is known to have worked in Heimberg from 1855 to 1866. The multi-branched Füllemann family from Steckborn produced at least four journeymen between 1812 and 1867: Hans Caspar Füllemann (1787–1826, worked in Opplingen for four months in 1812), Caspar Füllemann (dates of birth and death unknown, did several stints in Opplingen and Kiesen between 1860 and 1865), Cezar Füllemann (dates of birth and death unknown, worked in Heimberg in 1864/65) and Johann Melchior Füllemann (dates of birth and death unknown, did several stints in Kiesen, Heimberg and Münsingen between 1864 and 1867).

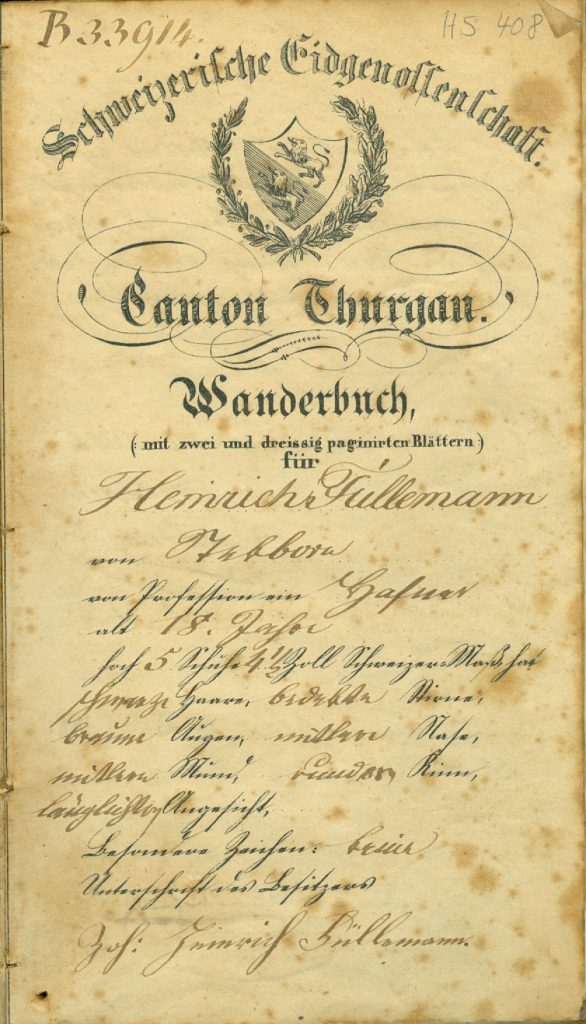

The journeyman’s book of potter Heinrich Füllemann II from Steckborn (housed in the Museum im Turmhof, Steckborn, Inv. no. HS 408, photo and pdf Steckborn Museum).

According to his journeyman’s book, potter Heinrich Füllemann II travelled around the region of Bern, and to Lausanne, Basel, Liestal, Hamburg, Lübeck, Schwerin and Lindau. In 1862/63, the potter Daniel Gräflein (1810–1882) spent 17 months working in Heimberg. From 1844 to 1849, Johann Martin Guhl (probably 1825–1892) worked as a journeyman in Hasle near Burgdorf, in Diessbach and in Kiesen. Two other journeymen that shared the same surname (Johannes and Johann Daniel) worked in Heimberg from 1873 to 1876 and from 1879 to 1881 respectively. Other journeymen with surnames like Kauf, Konf, Schär, Schneider, Wilhelm and Wüger are known to have worked in Kiesen and Heimberg between 1857 and 1867, but do not appear on any of the Steckborn lists of potters.

As a consequence, we can state that by the end of the 19th century, the Heimberg decorative style and its derivatives had spread throughout large parts of German-speaking Switzerland and possibly even the French-speaking areas (see MAHN AA 1247, MAHN AA 1249) thanks to travelling journeymen and their close associations with local potters. Therefore, we must refrain from speaking about “Heimberg pottery”, particularly when it comes to pieces in museum collections, most of which were acquired on the open market by or donated to the museums in question, but should only use the term “Heimberg-type pottery”. This slip-trailed ware, which was so typical of the late 18th and 19th centuries, was clearly produced by several different centres of manufacture in the German-speaking part of Switzerland (i.e. the Heimberg/Steffisburg, the Berneck and Steckborn regions, in the Canton of Schaffhausen and in Winterthur), and possibly also in some French-speaking areas (Cornol region, Moudon and Poliez-Pittet), in Baden-Württemberg (Staufen, Kandern) and, in the 1870s, even in France. In the absence of scientific analyses or excavation finds, it does not appear possible, given the current state of research, to associate individual products with specific places of production.

French: Céramiques de « style Heimberg » or Céramiques « à la manière de Heimberg »

German: Keramik «Heimberger Art»

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Babey 2016

Ursule Babey, Archéologie et histoire de la terre cuite en Ajoie, Jura Suisse (1750-1900). Les exemples de la manufacture de faïence de Cornol et du centre potier de Bonfol (Cahier d’archéologie jurassienne 37), Porrentruy 2016, besonders 174, 201-203.

Frascoli 2004

Lotti Frascoli, Keramikentwicklung im Gebiet der Stadt Winterthur vom 14. -20. Jahrhundert: Ein erster Überblick, in: Berichte der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 18, 2004, 127-218.

Heege/Kistler 2017

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Poteries décorées de Suisse alémanique, 17e-19e siècles – Collections du Musée Ariana, Genève – Keramik der Deutschschweiz, 17.-19. Jahrhundert – Die Sammlung des Musée Ariana, Genf, Mailand 2017, 369-375.