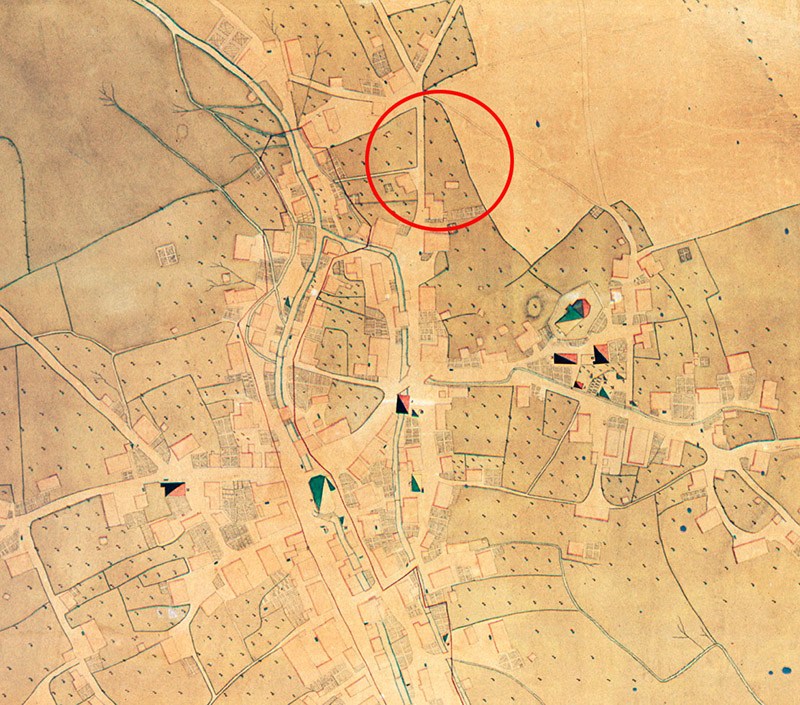

Langenthal, section of a local historical map by J. Oppikofer dated 1814. The site of the present-day property at 40–44 St. Urbanstrasse (formerly Badgasse) is circled in red. North-oriented map. (reproduced by ADB, graphic additions by Andreas Heege)

Andreas Heege, 2025

The parcel of land at 40–44 St. Urbanstrasse in Langenthal was examined by the Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern as part of a watching brief in 2010. Besides Roman and some high medieval remains, the main features uncovered belonged to a potter’s workshop. Archival records allowed the archaeologists to reconstruct the plot’s history of ownership. From the mid-18th century at the latest (perhaps from 1730?), four generations of potters from the Staub family had their workshops on the property (family tree). Pottery production ceased in 1870 at the latest.

Apart from sparse evidence of a workshop building as well as numerous wasters and a large variety of kiln props, the remains of two potter’s kilns and a secondary furnace were the most interesting finds from a history of technology point of view.

Overview of the working pit from the second phase and the kiln during the final phase. The remnants of the lining (68/78) of a working pit (97) that belonged to a kiln (46) and the lining (68) of a working pit (60) of another kiln (47) (Foto ADB, Leta Büchi).

The kilns had rectangular floor plans and were vertical potter’s kilns of the “Piccolpasso” type, the most commonly used kiln in post-medieval Switzerland. Judging by the wasters, the kilns were used to produce both crockery and stove tiles. During the late phase of the workshop, i.e. between c. 1840 and 1870, production was probably limited to stove tiles. The function of the small secondary kiln could not be determined beyond doubt, though the rubble provided some evidence that it may have been used to produce the lead-tin calx that was necessary to make faience glaze. The glaze itself was melted on the floor of the firing chamber in the kiln. The Staubs sourced their lead and tin from metal traders in Basel.

The oldest wasters found at the site dated from the late 18th century. As a consequence, it is not known what the wares may have looked like that were produced by the first potter named Staub. The product range of his son Daniel (1744-1802) is slightly better known, thanks to a number of wasters with high-quality Late Baroque Rocaille decoration. Unfortunately, it was not possible to identify the stove painter who worked for the Staub pottery at that time, though his work appears to have been closely related stylistically to some of the stove tiles from Aarau. It is possible that the workshop changed its range of shapes and decorations to the Louis XVI or Empire styles in the late 1790s, though again it is not known what these products may have looked like. What we do know, however, is that they must have been of a very high standard, as between August 1798 and May 1799, Daniel Staub supplied five stoves to be installed in the “National Palace of the Grand Council”, the legislative body of the Helvetic Republic, which at the time was under construction in Lucerne.

According to archival records and some surviving stoves and individual tiles, we can say that Daniel’s son Johannes (1767-1824), who ran the workshop from 1803 to 1824, worked with the stove painter Johann Heinrich Egli (1776–1852). This collaboration survived an economic crisis in 1819 and continued under Johannes Staub junior (1801–1865) until at least the 1830s. It was then that Johannes’ brother Johann David Staub (1809-1864), who had trained as a stove painter, took over Egli’s role.

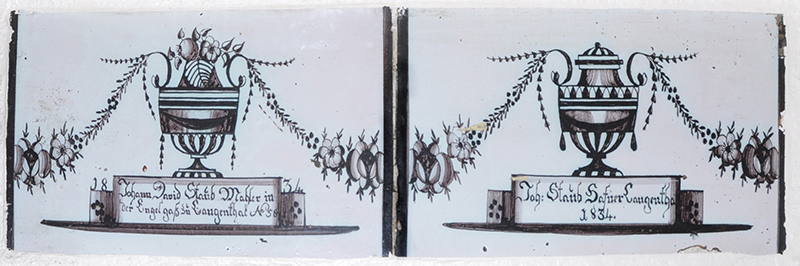

Grossdietwil, Canton of Lucerne, 1 Sandgrubenstrasse, Löwen inn. Preserved tiles from a stove made by Johannes Staub in 1834 and painted by Johann David Staub.

Health problems and a workshop fire (albeit not evidenced archaeologically) in 1845 eventually led to Johannes filing for bankruptcy in 1847, though Johann David Staub was able to acquire some of the assets and continued to run the business until his death in 1864.

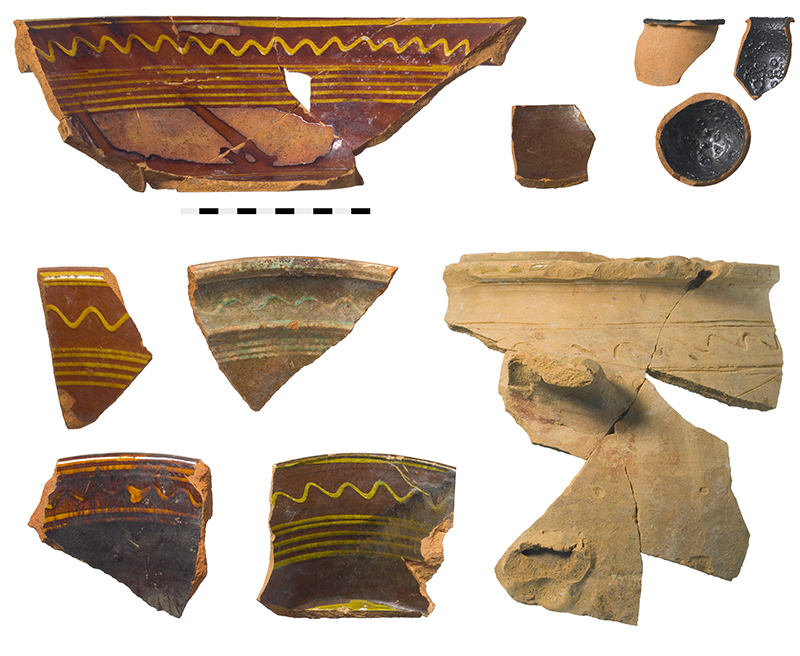

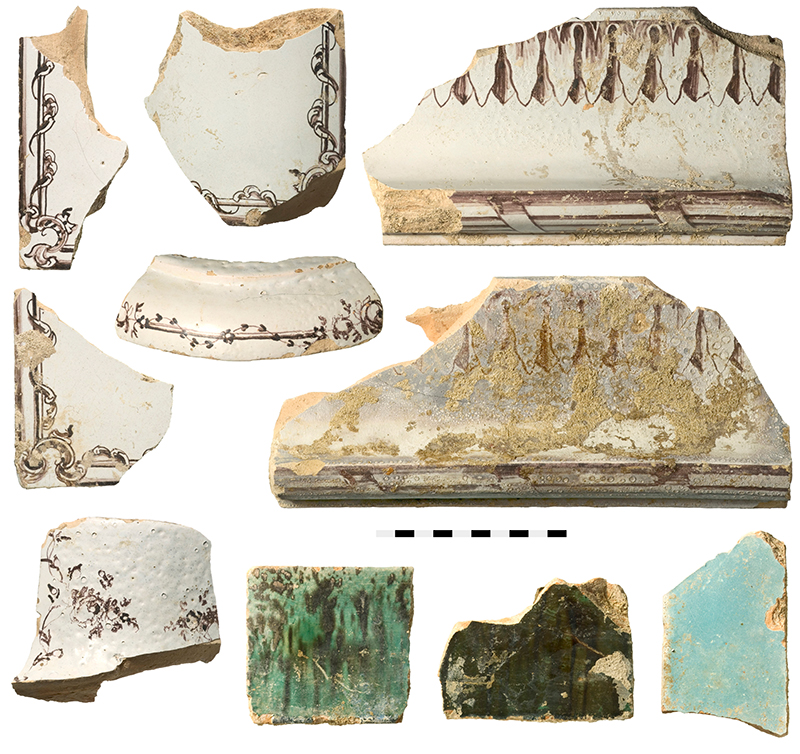

Langenthal, 40–44 St. Urbanstrasse. Ceramic finds from feature 45 (photo by Badri Redha, ADB).

The known range of crockery made by the Staub potters in the late 18th and first third of the 19th century mainly consisted of bowls with monochrome slipped decoration on a red coat of slip, poured slip and combed decorations as well as chamber pots and apothecary wares. In terms of the vessel shapes, it is not possible to distinguish between the Staubs’ wares and those made by other rural Bernese potteries.

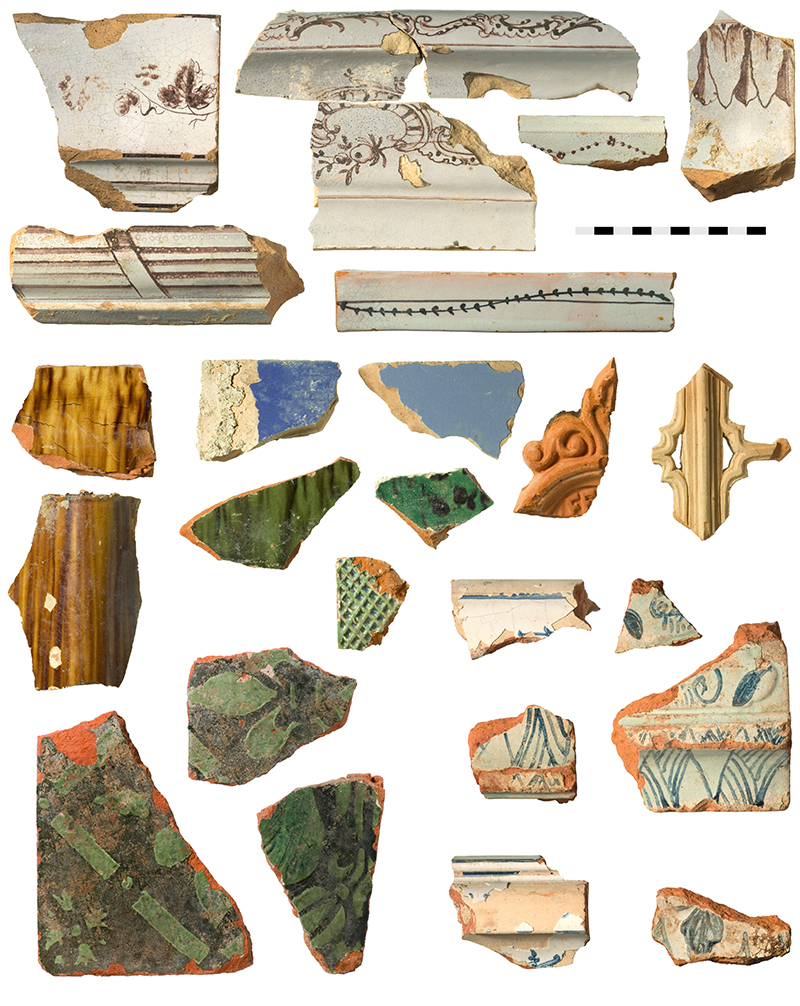

Langenthal, 40–44 St. Urbanstrasse. Stove tiles from features 85 and 49 (photo Badri Redha, ADB).

Some of the tiles bore a green and yellow-brown lead glaze with splashed decoration, while others had a faience glaze in white, blue or sea green. The only tiles with stencilled decoration were used residual pieces found among the workshop waste, but local production would certainly have been possible.

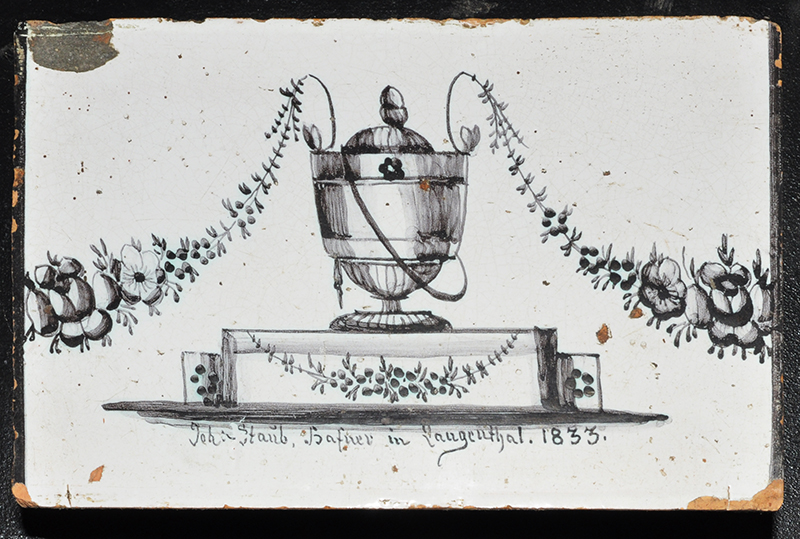

Panel tiles marked by master potter Johannes Staub (1801– 1865) from Langenthal. Dated 1831 and 1833, the tiles bear no painter’s marks but were probably decorated by Johann Heinrich Egli..

Panel tiles marked by master potter Johannes Staub (1801– 1865) from Langenthal. Dated 1831 and 1833, the tiles bear no painter’s marks but were probably decorated by Johann Heinrich Egli..

In keeping with the ever-changing decorative styles, the white faience tiles from the Staub workshop were mainly painted in manganese purple, a choice, which was probably influenced by tile painter Johann Heinrich Egli from Nussberg near Winterthur. Having worked in Aarau since at least 1813, his stylistic endeavours, which ranged from classicist landscape medallions deriving from close ties with potters’ workshops in Elgg, Canton of Zurich, and perhaps with the stove painter Conrad Kuhn from Rieden also in the Canton of Zurich, to mottos within shield-shaped frames, scrolls and Biedermeier-style vases or urns, left their mark not just on the stove tile production in Langenthal but also on the wares of numerous other potters whom he worked with. Tile stoves painted by Johann Heinrich Egli became significant elements of the Biedermeier-period stove landscape of the Bernese Aargau, the neighbouring Canton of Lucerne, eastern Aargau, the Fricktal valley and parts of the Cantons of Basel-Land and Zurich. Egli’s tiles were clearly very popular and became “style-defining”.

More in-depth research on Johann Heinrich Egli and the tiled stoves of the late 18th to the first half of the 19th centuries in the German-speaking part of Switzerland would be very welcome. Given the speed at which the stoves that still survive from the period are disappearing due, on the one hand, to the fact that the storage units of local heritage protection offices are crammed with architectural components and because there is a distinct lack of appropriate museum collections policies on the other, the time in which this work can be undertaken, is running out fast. Only when we have compiled a basic foundation of knowledge will we be able to make informed decisions as to what is worth recording and preserving.

Translation: Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Heege 2011

Andreas Heege, Langenthal, St. Urbanstrasse 40–44. Die Hafnerei Staub und ihre Werkstatt, in: Archäologie Bern/Archéologie bernoise. Jahrbuch des Archäologischen Dienstes des Kantons Bern, 2011, 209-287.

Heege 2015

Andreas Heege, Die Hafnerei Staub in Langenthal, Kanton Bern, 1730 bis 1870, in: Silvia Glaser, Keramik im Spannungsfeld zwischen Handwerk und Kunst. Beiträge des 44. Internationalen Symposiums Keramikforschung im Germanischen Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg, 19.-23. September 2011 (Wissenschaftliche Beibände zum Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums 40), Nürnberg 2015, 125-145.