Roland Blaettler 2019

Pottery from the Manufacture de poteries fines in CERAMICA CH

Jules Michaud died in February 1917 – according to his obituary in the Courrier de la Côte on 13th February (p. 1), he was “unexpectedly snatched away […] from his duties”. His son Louis (1874–1954) took over the running of the manufactory. He had been working in the business since at least 1910, as there is a record in the communal archive of Nyon that shows him to have been in contact with the authorities in relation to the company (communal archive of Nyon [ACN], Bleu A-72, meeting on 17th January 1910). The following year, Louis, a “faience manufacturer in Nyon” was voted onto the board of directors of the Swiss School of Ceramics (École suisse de céramique) at its founding assembly on 10th July 1911 (Tribune de Lausanne dated 13th July 1911, 2). That same year, he signed a letter to the municipality, where he described himself as a “junior employee at the manufactory” (personal communication from Madame Bourban-Mayor, Nyon city archivist). On 14th March 1917, just short of a month after his father’s death, Louis was appointed managing director by the shareholders’ general assembly. This shows that he had proven himself to be a valuable asset to the company (Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce [SOGC], Vol. 35, 1917, 498).

The name of the company was in a state of flux for a long time. A document on water rights dated September 1880 (see the chapter “Nyon – the refined white earthenware manufactories (2)”) mentions both the “Manufacture de poterie de Nyon, société anonyme” and the “Manufacture de poterie fine de Nyon”. Subsequently, both variations appear to have been used side by side. In the first volume of the SOGC, which was published in 1883, the business appears as the “Manufacture de poteries de Nyon”, whereas a sheet of writing paper with a printed letterhead from 1897 has the name “Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon”. When Louis Michaud took over the company, this was fairly quickly rectified: in June 1917, the shareholders agreed to a new company name: “Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon S. A.” (SOGC, Vol. 36, 1918, 1044).

The communal archive of Nyon houses an illustrated catalogue from the manufactory. Consisting of unbound photographic plates and a title page with the heading “Album – Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon S. A. – Louis Michaud, directeur”, it is clearly incomplete (ACN, R 1224, labelled as “Album Michaud” in the inventory notes). We would assume that the document dates from around 1917/18, i.e. shortly after Louis Michaud took over the business and changed the company name. The shapes are very much characterised by the eclectic tastes that prevailed around the turn of the century.

The decorated objects mainly have printed floral motifs. Examples include the shape of the vessel labelled MHPN MH-2013-46, though it has a non-floral printed pattern; the tureen MHPN MH-2015-532, which is undecorated; the old sauce boat model MHPN MH-2003-118 and the white dish MHPN MH-2000-125. Some decorative pieces, vases and flowerpots, have relatively elaborate applied decorations.

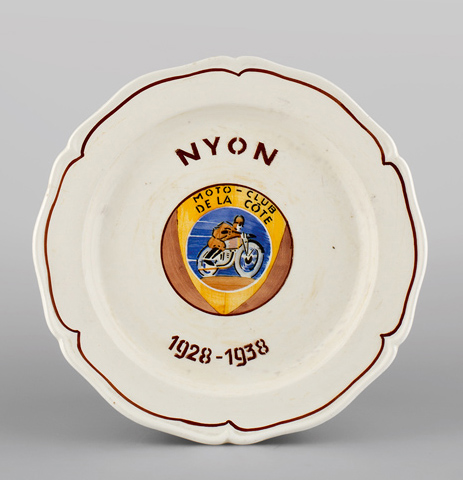

Over the course of the 1920s, the products changed quite considerably, first with regard to their designs. The transfer-printed motifs became increasingly colourful, particularly on pieces to commemorate anniversaries or other events (MHPN MH-2000-91; MHPN MH-FA-4656).

Most importantly, however, painted patterns reappeared on pieces from the everyday production for the first time in over half a century; these were made by painters and paintresses employed by the manufactory (MHPN MH-FA-4538B; MHPN MH-1993-341; MHPN MH-FA-4531; MHPN MH-FA-4577; MHPN MH-FA-4566; MHPN MH-2015-410; MHPN MH-2006-3; MHPN MH-2015-407; MHPN MH-2015-406).

This resurgence of painted objects has been associated in the literature with Henri Terribilini (1898–1982) (see the chapter on “Henri Terribilini”). He decorated some of the refined white earthenware objects from Nyon in 1917, probably as a freelance decorator, when his tutor, Nora Gross, was collaborating with the factory (MHPN MH-FA-10010; MHPN MH-1998-140).

In May 1920, the young artist moved to Nyon for a year and worked with Georges Vallotton (see the chapter on “Vallotton, Georges”). It is quite possible that he occasionally worked for the manufactory during that time. In 1925, Terribilini made Nyon his permanent home when he was hired by Michaud to run the painting shop. He remained in the job until 1928 and was very obviously responsible for some of the manufactory’s most popular brushwork decorations during the period between 1925 and 1935 (MHPN MH-FA-10006; MHPN MH-FA-4037; MHPN MH-FA-4039; MHPN MH-FA-4648; MHPN MH-2014-18; MHPN MH-2000-75; MHPN MH-FA-10005; MHPN MH-FA-4400A; MHPN MH-2003-110; MHPN MH-FA-4398; MHPN MH-205-389; MHPN MH-FA-4564).

When he moved to Nyon temporarily in 1920, the residents’ registration office listed Terribilini as hailing from Langenthal, where he had worked as a porcelain painter (ACN, resident’s registration office dossier). The products from Langenthal include several examples of painted floral designs on polychrome backgrounds that are reminiscent of certain motifs from Nyon. The Swiss National Museum in Zurich has in its collection a cup from 1918 (SNM LM-59169) and a vase from 1924 (SNM LM-158592); the Musée Ariana has two vases from the period around 1920 (MAG AR 2002-309; AR 2007-113 – Schumacher and Quintero 2012, Fig. p. 67).

When comparing these designs with the object from Nyon (MHPN MH-FA-4564), it seems plausible that Terribilini could have introduced this type of decoration to the Nyon manufactory when he began working there in 1925. What we cannot say, however, is if he created the designs in Langenthal. As he was only working there as an “assistant decorator”, it is rather doubtful.

The manufactory’s shapes were also constantly being updated – beginning with the vessels for holding liquids, where we find rather bold conical profiles (MHPN MH-2015-408; MHPN MH-2000-69).

The vessels that were made to contain food, like tureens, tended to be made in the more traditional shapes, some of which continued to be made up until the 1940s (MHPN MH-1999-78; MHPN MH-2015-532; MHPN MH-FA-4549).

The communal archive of Nyon houses a sales catalogue printed for the market in the German-speaking part of Switzerland entitled “Steingutfabrik Nyon A.-G.” (ACN, R 1224, cited in the notes accompanying the inventory concerned as “Steingutfabrik Nyon”). In our opinion, this document, which very clearly attests to brushwork decoration dominating the range of products, dates from the period between 1920 and 1925. It includes a number of services, wash jug and basin sets and vases, all adorned mainly with brushwork motifs.

Specifically, the catalogue includes a dish of the same type as MHPN MH-2014-18, lidded containers similar to MHPN MH-2015-410 and a vase that is highly reminiscent of MHPN MH-FA-4037.

A page that includes the pricelist also shows the new factory mark, which consisted of a round medallion with the traditional Nyon fish and the initials “MN” (Manufacture – Nyon). The word “Nyon” was added below the medallion. This mark was stamped on the objects using a blue underglaze paint (e.g. MHPN MH-2006-4). A specific variant of the mark was used on the hand-painted pieces (MHPN MH-FA-4400H). So far the earliest use of this new mark dates from 1925, the latest from 1931. It was probably introduced between 1920 and 1925.

It was replaced in 1933 by a new stamped mark consisting of the Nyon coat of arms and the name “Nyon” in green underglaze paint (MHPN MH-1993-47; MHPN MH-2015-368). As far as we are aware, this green mark was used exclusively on pieces commemorating anniversaries and events in 1933.

In 1934 it was replaced by a blue mark (MHPN MH-2000-170; MHPN MH-FA-10033A to -C). These blue marks are extremely rare.

They appear to have been replaced quickly, probably in the same year, by a brown-black variant (MHPN MH-1997-39; MHPN MH-FA-4438), the latest use of which has been found on a piece from 1939.

Another variant in brown-black can be found on the commemorative pieces and promotional wares from 1937–1939; the addition of the word “Pinx’ Man” (MHPN MH-2015-422) is rather unusual and appears to be pointing to a hand-painted design that is always combined with a stencilled motif (see also Ethenoz-Damond 2008, 62).

In the 1930s, the company experienced quite a few changes, both from an aesthetic and from a technological point of view, as three eminent personalities joined the business. The first to join in 1930 was Josué Rieben (born in 1907), who was hired as the manufactory foreman. He had trained as a modeller at the Swiss School of Ceramics. The residents’ registration office records noted that he had come to Nyon from Château-d’Œx. After a few years of working for the company, he also became the manufactory’s travelling salesman (Ethenoz-Damond 2008).

Another important person was Henri Crétenet (1905–1999), a clockmaker and engraver from the Jura region, who was forced by the economic downturn to make a career change. Crétenet was hired in 1933. The residents’ registration office listed him as a “ceramic worker” from Monthey. Thanks to his fine-motor skills he quickly climbed the ladder and became head of the decorating shop (Pelichet 1985/2, 37; Desponds 1999, 81; Ethenoz-Damond 2008, 52). His speciality was the making of stencils which were used to create polychrome designs either by air-brushing or by manually paint brushing motifs cut out of sheets of aluminium. The technique was used until the 1970s, mainly on commemorative and anniversary objects (MHPN MH-2015-415; MHPN MH-2015-416; MHPN MH-2015-436; MHPN MH-2015-417; MHPN MH-FA-4598; MHPN MH-2015-365; MHPN MH-FA-4491; MHPN MH-1993-78; MHPN MH-2000-54; MHPN MH-2000-170; MHPN MH-FA-4650; MHPN MH-1997-39; MHPN MH-2003-6; MHPN MH-2005-6; MHPN MH-FA-4658; MHPN MH-2015-409; MHPN MH-2015-52; MHPN MH-FA-4732C; MHPN MH-2015-422; MHPN MH-1993-4; MHPN MH-2015-447; MHPN MH-FA-4399; MHPN MH-2010-55; MHPN MH-FA-10025A; MHPN MH-2000-89; MHPN MH-FA-4586; MHPN MH-2015-420; MHPN MH-2015-369).

Crétenet not only made the stencils but also designed some of the motifs, as attested to by the initials “HC” alongside some of them (MHPN MH-FA-4518; MHPN MH-2000-47).

His initials are only rarely found on classic transfer-printed designs (MHPN MH-2015-437).

In 1947, Crétenet moved to Prangins, but returned to Nyon in 1950 to move into a flat in the manufactory building. At that time, he was registered by the residents’ office as “head of production”. It is quite possible, of course, that he had already taken on this new role before he ever moved to Prangins.

The third new arrival was responsible for some innovative shapes. In 1932, Josué Rieben hired Louis Guex (1910–1988) as a modeller (see the chapter “Louis Guex, art pottery”). The records of the residents’ registration office list Guex as a “ceramic modeller”. His role at the manufactory involved the creation of new shapes as well as – and perhaps more importantly – the supervision, enhancement and production of plaster of Paris moulds. Guex had honed his skills in this particular field when he worked for Paul Bonifas in Ferney-Voltaire.

The pedestal jug with flattened circular body is a characteristic shape that can be attributed to Louis Guex (MHPN MH-2003-6; MHPN MH-2005-6; MHPN MH-FA-4399; MHPN MH-FA-4499B; MHPN MH-FA-10037). Many such jugs have the initials “LG” (MHPN MH-2015-375).

Guex also redesigned some of the more classical shapes like plates with indented rims (e.g. MHPN MH-1997-39). With regard to the vessels presented here, these innovations can be seen in the commemorative objects from 1938 onwards, but it is indeed possible, that they were introduced before that.

In the 1920s, the manufactory produced the first all-over brushwork decorations that showed a new sense of style which was characterised by the fact that the actual essence of the pottery was concealed in a way (e.g. MHPN MH-2015-406; MHPN MH-2006-3; MHPN MH-FA-4039). The idea was to make refined white earthenware, most of which was industrially produced, to look like faience, which was considered to be more elegant and more “artful”. This tendency only intensified over time, and by the early 1940s, opaque or matt glazes had replaced the customary transparent glazes.

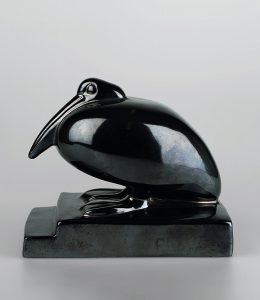

The main glazes, which were known as “matt” glazes at the workshop (Ethenoz-Damond 2008, 58–60), were a beige with a slightly pinkish hue (“pink” glaze – MHPN MH-FA-4553; MHPN MH-FA-10037; MHPN MH-FA-4557; MHPN MH-FA-4529) and a glossy black, which was reminiscent of the slip used by Paul Bonifas in Ferney-Voltaire to make his famous “terres lustrées noires” (MHPN MH-2000-116; MHPN MH-FA-4457; MHPN MH-FA-4499B; MHPN MH-FA-4455).

This particular glaze was probably created in 1932 after Louis Guex had joined the manufactory and can be explained by the fact that Guex had worked as a modeller at the Bonifas workshop in 1931/1932.

Louis Guex’s creative style can also be seen in a vase with a dancer, which was designed to look like a late Art Deco object (MHPN MH-2015-387; MHPN MH-1994-1), and in the animal figurines which were newly added to the manufactory’s product range.

During the Art Deco period, many ceramic studios in Europe began to create animal figurines, often from refined white earthenware. Paul Bonifas in Ferney-Voltaire brought out various Swiss artists’ sculptures (see below). The manufactory in Nyon took the same path, albeit somewhat belatedly. According to Pelichet (Pelichet 1992), the first experiments with this art form in Nyon were made at the request of the famous animal sculptor, Édouard Marcel Sandoz, for his own use (MHPN MH-2015-354; MHPN MH-2015-352; MHPN MH-2015-355 and -356).

Pelichet attributed the first original pieces to Josué Rieben and dated them to 1936 (MHPN MH-2015-340; MHPN MH-2015-376; MHPN MH-2015-341; MHPN MH-2015-361).

This particular product line very clearly hit its stride when Louis Guex joined the company in 1932. He had trained as a ceramic modeller with Bonifas and adopted several shapes that had been created by the famous potter from Ferney-Voltaire a few years previously. This is very obvious when we compare the original figure of a pelican made by the Bonifas workshop modelled on a sculpture by Hélène Wyss-Pilet (MHPN MH-1994-3) to the version from the factory in Nyon which was slightly reworked by Guex (MHPN MH-2015-362; MHPN MH-1994-2).

The fact that another object modelled on a Wyss-Pilet piece, a chinchilla figurine, was also made by Bonifas originally, did not stop Guex from marking it with his own monogram (MHPN MH-2015-375). Even though Guex probably made the plaster of Paris mould for this figurine, the use of his own monogram appears a little impertinent. The monogram did, in fact, prompt Pelichet to attribute the chinchilla to Guex.

The same phenomenon can be observed on a figurine modelled on an Édouard Marcel Sandoz sculpture (MHPN MH-2015-434).

Other figurines bear the name or the initials of their original creators, for example those by Juliette Mayor (1896-1979): MHPN MH-2015-442; MHPN MH-2015-378; MHPN MH-2015-367; MHPN MH-2015-385; MHPN MH-2015-360; MHPN MH-2015-363.

As we have seen, Louis Guex probably did not just rework models created by other artists, but because he used his own monogram in a somewhat dubious manner in some cases, it is not easy to identify his own original creations (perhaps MHPN MH-1994-6 or MHPN MH-2015-377). Louis Guex left the manufactory in 1946 to set up his own business (see the chapter Louis Guex, art pottery).

In the mid-1930s, during the world economic crisis, the manufactory went through a number of upheavals as attested to by various records in the communal archive (ACN, R 810). A report written by Josué Rieben in May 1935 came to an alarming conclusion: the quality of the production had taken a nosedive. “Too much second-rate ware, and even worse, too much third-rate ware”. According to Rieben, it was impossible to obtain “decent and saleable works” from the existing staff. The workplace atmosphere had become toxic and any attempts to introduce innovations were scuppered. He believed that the entire workforce should be fired and only the best members of staff rehired. The company board of directors, who were also worried about the future of the manufactory, had already approached Albert Jaccard (1897–1965), a trained engineer who, they hoped, would lead the company out of the crisis.

In a letter dated 5th December 1935, banker Alfred Baup, who was chairman of the board from 1917 to 1926 and again from 1936 until 1955, informed his fellow directors that Jaccard was willing to invest his reserved capital of 50,000 Swiss francs and called this an “unexpected offer and an opportunity that will not arise again!”. An undated letter by Jaccard confirms the offer “provided the conditions stipulated in [my] correspondence of 5th March concerning the potential takeover of the majority of the company’s joint capital are upheld”. On 27th March 1936, he provided two draft contracts concerning the collaboration to reorganise the manufactory (not included in the dossier). The municipal council meeting on 20th April 1936 was informed by “Monsieur Albert Jaccard, the new director of the manufactory”, that he had been tasked with examining the possibility of reorganising the company and that the board of directors was contemplating closing down the manufactory. In a bid to avoid staff redundancies, he was asking for a considerable discount on the price of electricity the council was charging. On 18th May, the council recorded that, according to Jaccard, only one staff member had been dismissed, while the police commissioner recorded five dismissals (ACN, Bleu A-88).

The reorganisation of the company management was sanctioned by the general assembly of shareholders on 22nd April 1936 (SOGC, Vol. 54, 1939, 1343): Article 23 of the statutes was changed and now stipulated that the company management would be “conferred on a director or on a delegate selected by the board of directors. Both the director and the delegate of the board of directors will be authorised sole signatories”. At the annual general meeting, which took place that same day, the shareholders voted for Louis Michaud and Albert Jaccard to become new members of the board of directors. Alfred Baup was its president, Louis Michaud the secretary. Albert Jaccard was selected as the delegate of the board. Louis Michaud would no longer hold the position of managing director.

Jaccard thus effectively became the new managing director of the company, even though he was officially a delegate of the board. The local press regularly identified him as the “director” of the manufactory. The appointment of Michaud as an ordinary board member – a function, which he would hold until his death – pushed him into the background, while Albert Jaccard certainly added new momentum to the company. He had high-ranking positions in various businesses throughout the region, including the railway company Nyon–Saint-Cergue–Morez, the Gland–Begnins and Rolle–Gimel tramlines and the La Côte electricity works. He was also active in politics, as a member of the municipal council and as a Grand Councillor (Tribune de Lausanne dated 22nd August 1965, 13).

When looking at the objects in the collections, we can generally see an improvement and more consistency in the production starting in 1937/38. The basic fabric had a warmer colour, and the cool white had been replaced by a white with an ivory hue. The shapes were better worked overall and more consistent. In Henri Crétenet and Louis Guex, the manufactory had clearly won two highly skilled technicians who also expected the work to be of a higher standard.

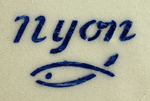

Several new factory marks were introduced from 1939/40 onwards, all of which were stencilled in blue underglaze paint. Unfortunately, there are not enough dated pieces to ascertain the exact timelines for the individual marks. Moreover, some variants appear to have been used concurrently. Some of the marks simply consist of the placename “Nyon” with one capital letter and lower-case letters in italics (MHPN MH-2000-89) – on objects manufactured between 1942 and 1945 – or in sans-serif capital letters (MHPN MH-FA-4597) – on objects made between 1945 and 1949.

The first variation is possibly slightly earlier than the second, but more research still needs to be carried out.

One variant of the first mark consisted of a stylised fish with the placename “Nyon” (MHPN MH-2010-55; MHPN MH-FA-10025A). We have found it on two plates from 1942. The stylised fish was registered as a factory mark on 8th July 1939(Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, Vol. 57, 1581).

The same motif can also be combined with a third variation of the placename (MHPN MH-2000-172), which we have so far only encountered on a single object.

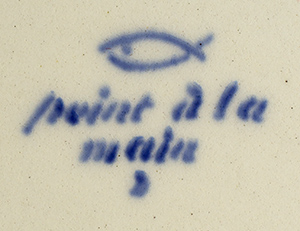

The most common mark seems to have been the stylised fish without the placename but with the words “paint à la main” [hand painted] (MHPN MH-2000-45; MHPN MH-FA-4570). It is accompanied by a single letter beneath the mark which identified the decorator and could thus be used for quality control. The letter “D” in the example here referred to Gabrielle Damond, a paintress who worked at the manufactory from 1938 to 1952 (Ethenoz-Damond 2008, 62).

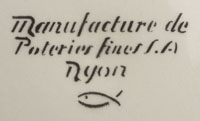

The final variation was found on the back of a commemorative dish from 1950 in the collection of the Museum of Old Moudon. Here, too, we can see the stylised fish, only this time it is accompanied by the label “Manufacture de Poteries fines S. A. Nyon” (MVM M 1936).

Fernand Jaccard, chemical engineer, succeeded his father in 1951 (SOGC, Vol. 69, 1951, 992). By 1965, the manufactory was still producing 300 metric tons of crockery each year, which equates to one million pieces; some of the series comprised up to 200,000 units and were manufactured for wholesalers. Partial automation had allowed the company to reduce its workforce from 60 to 30 employees over the course of 12 years (Nouvelle Revue de Lausanne dated 25th March 1965, 15). By the early 1970s, the financial situation of the company had become rather precarious. Because of the large amounts of ceramic imports from abroad, local manufacturers were no longer able to compete, and both the personnel costs and the raw material prices had risen.

In April 1972, Fernand Jaccard left Nyon and accepted the offer of a post as a lecturer at the School of Applied Arts in Vevey (24 Heures dated 18th April 1972, 19). In June 1972, Josué Rieben, Henri Crétenet and Noëlie Barbey were authorised as joint signatories (SOGC, Vol. 90, 1972, 1577). In February 1974, the manufactory put its workers on short time, “because of unforeseen developments in the market”, although some left of their own volition to work abroad, mainly in France. After around a third of the workforce had been let go in 1973 the company now employed approximately 20 workers, (24 Heures dated 2nd/3rd February 1974, 17 [description of the production processes] – 24 Heures dated 5th February 1974, 19).

There were persistent rumours about a closure of the manufactory until the spring of 1977, when the board of directors pinned their final hopes on Maurice Colin, the owner of a pottery in the Valais region. On 3rd May 1977, he was appointed director of the company replacing Fernand Jaccard. Colin was a Belgian citizen who, together with his wife, had set up a pottery called “Valcera” in Châteauneuf-Conthey in the Canton of Valais in 1961. He decided to close his factory in the Valais and planned to move his equipment to Nyon, as pooling the customer base of both companies seemed to create a large enough marketplace for one company to survive. The company “Valcera” was dissolved in December 1978 (24 Heures dated 5th May 1977, 19 – SOGC, Vol. 79, 1961, 2764 – SOGC, Vol. 97, 1979, 420). The change of management in Nyon was officially registered in June 1977, and in July, Fernand Jaccard was voted onto the board of directors (SOGC, Vol. 95, 1977, 2042). The new man of the moment had very little time to create a new collection, so he “adopted many of the old shapes and copper plates [the etched plates to produce the transfer-printed designs]”. At an extraordinary general meeting on 4th April 1978, the shareholders decided to cease production at the end of the month. Colin bemoaned “the lack of courage shown by the board of directors”. Max Thomas, one of the leading members of the board, stated that while the financial situation of the manufactory was stable, it would not be an option to risk the entire company capital (24 Heures dated 5th April 1978, 19).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

Sources:

Communal Archives of Nyon [ACN], Série Bleu A, Registres de la Municipalité – Contrôle des habitants – R 1224, Fonds Josué Rieben – R 810, Fonds Fernand Jaccard

Vaud press and phonebooks, accessed via the “Scriptorium” website of the Cantonal and University Library in Lausanne.

The Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, accessed via the website e-periodica.ch.

References:

Blaettler 2017

Roland Blaettler, CERAMICA CH III/1: Vaud (Nationales Inventar der Keramik in den öffentlichen Sammlungen der Schweiz, 1500-1950), Sulgen 2017, , 57-60, 380, 414, 418.

Desponds 1999

Liliane Desponds, Terre d’argile et mains agiles. La poterie de Nyon 1860-1978. Collection Archives vivantes. Yens-sur-Morges 1999.

Ethenoz-Damond 2008

Gabrielle Ethenoz-Damond, La Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon. Souvenirs d’une ouvrière 1938-1952. Nyon 2008.

Maggetti et Serneels 2017

Marino Maggetti et Vincent Serneels, Étude archéométrique des terres blanches poreuses («faïences fines») des manufactures de Carouge, Jussy, Nyon et Turin. Revue des Amis suisses de la céramique 131, 158-222.

Pelichet 1992

Edgar Pelichet, Les charmantes faïences de Nyon. De surprenants animaux et des vases. Manuscrit inachevé, 1992 (Archives du Château de Nyon).

Schumacher et Quintero 2012

Anne-Claire Schumacher et Ana Quintero (éd.), La manufacture de porcelaine de Langenthal, entre design industriel et vaisselle du dimanche – Die Porzellanmanufaktur Langenthal, zwischen Industriedesign und Sonntagsgeschirr. Milan/Genève 2012.