Pottery from Bonfol in CERAMICA CH

Ursule Babey, 2019

The small municipality of Bonfol, on the border between the Canton of Jura and the Alsace region of France, is known mainly for the extraordinarily high quality of its clay. The community has a long-standing pottery-making tradition. The earliest record of the use of its excellent clay for the production of ceramic objects is a financial statement from the nearby town of Delsberg whose authorities ordered a tiled stove for their town hall on 15th August 1544 to be made by Küna, son of Henri from Bonfol. It has not been possible so far to identify tiled stoves from Bonfol by archaeological means. Nor do the records allow us to ascertain whether the potters from Bonfol supplied crucibles to the forest glassworks at Court (Canton of Bern, 1699–1714) for the production of drinking glasses. Thanks to other excavations, which were carried out during construction of the A16-Transjurane motorway (Porrentruy-Grand’Fin and Rebeveulier-La Verrerie), it has been possible to identify ceramic items of everyday use that were widespread throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and to confirm their provenance from Bonfol workshops by ceramic analyses. The popularity of these wares can be attributed to two factors: firstly, the geological circumstances that produced a clay that was naturally resistant to heat, and secondly, the geopolitical context of the locality which favoured the extraction of this raw material.

The special geological circumstances and their impact on the technological limitations in processing the raw materials

The raw materials that were extracted under the label “argiles bigarrées de Bonfol” – “colourful Bonfol clays” were clays of fluvial origin dating back to the end of the tertiary period. They occurred in small, lenticular deposits. Because they were almost completely devoid of lime, the clays were resistant to heat. Bonfol clay did not require much processing and was used almost as it came out of the ground. After a period of maturing in the open air, it was cleansed by removing inclusions visible to the naked eye, including pieces of wood, leaves or small pebble stones. This step was carried out by the potters shortly before they put the clay on the wheel to shape it. No further components or tempering agents were added to it. No other clay deposits of similar quality have ever been discovered in Switzerland.

As well as the positive aspect of the clay being resistant to heat, the lack of calcium oxide or lime also had a negative impact in that it made it harder for the glaze to adhere to the clay. This meant that the potters at the time were forced to use a transparent lead-based glaze which is easily identified due to its yellow colour. Making the glaze in hand-driven grinders not only posed a risk to the potters’ health, but it was also not resistant to acid and thus had a tendency to dissolve when it came into contact with food or drink.

Up to the late 20th century, the products were fired in large upright wood-fired kilns. This led to an over-exploitation of the nearby forests and some workshop owners were fined for offences against forest laws (burglary of wood), which impacted the already precarious economic balance of their businesses. In order to limit the use of wood as much as possible, potters only fired their products once, a solution used specifically for this type of pottery.

Pottery making not only requires ample clay deposits, but there must also be easy access to them. In the Ancien Régime, clay, much like iron ore and rock deposits, was part of the bergregal, and thus came under the ownership of the Prince-Bishop of Basel. In a bid, however, not to hinder the productivity of the potters in the region, he gave them unlimited access to the clay deposits free of charge. The only condition was that the pits from which the clay was extracted had to be fenced off to prevent cattle from breaking their legs. Also, once the potters were finished with a particular site, the pit had to be backfilled.

How the potters were organised

Up to the 19th century, the use of heat-resistant ceramic vessels was widespread, because most people cooked either on open fires or on wood-fired cooking stoves. The pottery produced in Bonfol was perfectly adapted to the requirements of the local population and therefore in big demand. Being aware of their de-facto monopoly based on the quality of their raw material, the potters, consciously or unconsciously, organised themselves in an inventive and independent manner. Within the locality, their socio-economic group was of great importance, as almost the entire population was involved in some way or other in the manufacture of pottery, be it directly as potters, journeymen and apprentices or indirectly as clay extractors, woodcutters or salespeople involved in trading the wares. This led to very strong ties between the different families, which in turn resulted in a strict professional endogamy and a strong feeling of being among one’s own kind.

It was not until the potters were confronted with the outside world, such as the corporations based in Pruntrut/Porrentruy, that the workshop owners joined forces. The main objective, which was ultimately achieved, was to avoid their obligation to train new apprentices and, in particular, to lose them again during their journeyman years.

Because the Bonfol clays were of such good quality and thus easy to process, the local potters had limited expertise in their field of work. Their knowledge did not go beyond what was handed down from one generation to the next, which meant that they were not able to compete in working environments outside of their own and therefore tended to remain within the locality of Bonfol. There are only a few Bonfol potters known to have emigrated. They generally worked on their own in family workshops, preferably with a son, an apprentice or a journeyman. The only time they were forced to collaborate with colleagues was when they needed to fire their wares, as there were fewer kilns than potters in the 19th century. We can assume that joint use or renting of potters’ kilns was the norm, although there are no known notarial documents to support this assumption.

In order to secure the sale of their rather fragile wares, the Bonfol potters tried to offer them at unbeatable prices. They reduced their time, energy and financial investment across the entire production chain: the clay was used with hardly any preparation beforehand, the vessel shapes were simple and standardised, and the stylised slip trailing was limited to a small range of colours (white, dark-brown, greenish hues). Only tableware was painted; cookware and storage vessels remained undecorated and only those containers that came into contact with food or liquids were glazed. The lead oxide glazes were usually acquired in Basel. Finally, the products were fired only once, cutting down on the use of fuel

While the wares that resulted from this saving in costs were not particularly pleasing from an aesthetic point of view, the products certainly remained economically viable. Thanks to mineralogical, petrographical and chemical analyses carried out by Gisela Thierrin-Michael it was possible to characterise this particular range of wares, which in turn informed the definition of a series of features based upon which it is now possible to identify the objects from this group by the naked eye and without the need for any further analyses. Their place and economic importance within the abundance of modern-era utility ware has therefore been appropriately recognised.

Bonfol pottery was sold throughout almost all of Switzerland north of the alps, in southern Germany and in eastern France, and this is attested to either by documentation or by archaeological finds. One piece of evidence worth mentioning were the market regulations for the Swiss town of Freiburg. They show that, because the potters of Bonfol offered a popular commodity which could not be produced elsewhere, they were the only non-local pottery producers that were permitted to sell their wares in the town. The products were sold by hawkers and door-to-door salesmen, some of whom brought their entire families with them on the road, while other traders offered the wares for sale at annual fairs in the larger towns and cities. Their success, however, did not mean that the craftsmen made a lot of money or gained a higher standing in the community as reputable citizens. They did not see themselves as individuals or artists, which is why the vessels were not usually signed. While their work did not alleviate their poverty, as shown by inventories compiled after some of them died, it did guarantee their independence, which appears to have been more important to them.

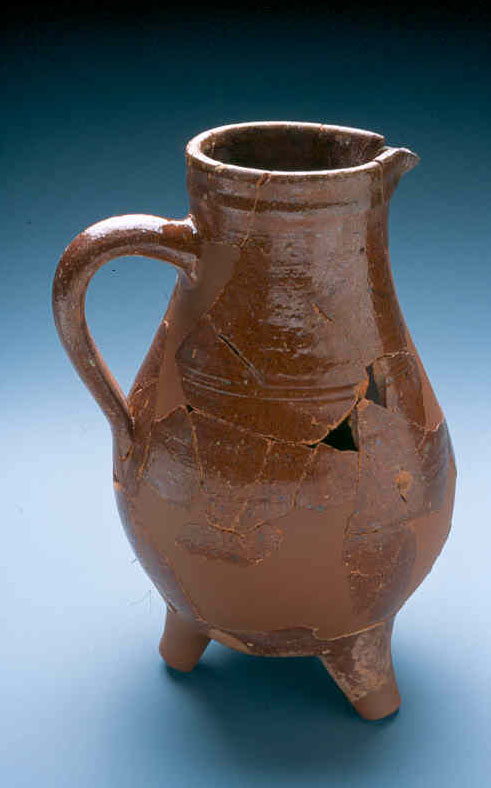

Tripod jug from Bonfol. Height: 26 cm. Late 18th to early 19th century. Porrentruy-Grand’Fin. From the collection of the Amt für Kultur der Republik und Kanton Jura – Abteilung Archäologie. Photo: OCC-SAP, Bernard Migy.

The range of products

The pottery from Bonfol was generally characterised by the warm brownish-ochre colour that resulted from applying a transparent, yellow glaze directly onto the clay, which turned red during the firing process due to its iron oxide content (yellow + red = brown). No coat of slip was applied between the clay and the glaze. The breaks show a considerable amount of fine siliceous temper (making up 20 to 30 percent of the fabric) with the largest grains rarely exceeding 2 mm. Most of the temper consists of large, bright red-brown clay lumps containing quartz and iron, as well as potash feldspar, soda-lime feldspar, mica or hornblende. All components are embedded in an often fibrous matrix.

Deep dish. Diameter: 31 cm. Porrentruy-Grand’Fin. Late 18th and early 19th centuries. From the collection of the Amt für Kultur der Republik und Kanton Jura – Abteilung Archäologie. Photo: OCC-SAP, Bernard Migy.

Cookware and storage vessels were undecorated. Tableware, on the other hand, and even chamber pots were systematically slip-trailed using a white-firing slip. Under the yellow glaze, however, the slip trailing appears yellow, and sometimes potters also applied green or dark-brown glaze to make the objects look more refined. Unglazed slip-trailing is rarely found.

Tripod skillet with a hollow handle from Bonfol. Diameter: 24 cm. Porrentruy-Grand’Fin. Late 18th and early 19th centuries. From the collection of the Amt für Kultur der Republik und Kanton Jura – Abteilung Archäologie. Photo: OCC-SAO, Bernard Migy.

Particularly popular due to their resistance to heat, the vessels from Bonfol were suitable for cooking on open fires or in ovens and were usually undecorated. The fondue skillet was and still is the most widely used vessel among them; its popularity and widespread sales resulted in the region around Porrentruy becoming better known. Up to the mid-20th century, it was a simple round cooking pot with a flat base or three feet and a horizontal handle, which was usually hollow. Some examples had bevelled rims. They were almost never decorated. Their diameters ranged from 15 cm to 30 cm. Over the course of the 19th century, they were sometimes glazed on both sides. Besides cookware there were also oven-proof vessels or oval roasting dishes, as well as frying pans with or without feet and tripod jugs which could be placed in the embers.

However, the range was not limited to cookware. The same clay was also used to make multi-purpose vessels (tureens in the shape of truncated cones without pouring lips or handles) and tableware (deep dishes in various sizes). Round storage pots with two vertical handles and bevelled rims, various types of lids and chamber pots with wide everted rims completed the range of vessels.

From 1820, several brick yards began to use the local clay to produce roof tiles; this had been prompted by one of the potters, who wished to diversify his range of products. From 1889, roof tile production became mechanised. However, following a fire in 1919, the brick yard ceased to operate. Tiles from the mechanised brick yard, now more than one hundred years old, still cover roofs in the region, which proves that heat-resistant clay can also be used for other purposes.

Decline, industrial revival and end of mass production

While the community of potters consisted of no more than nine members in 1751, the number of workshops had grown to 24 by 1764. Between 1770 and 1813 the number stabilised between 24 and 35 heads of families declaring themselves to be potters. The period between 1817 and the mid-19th century was the heyday of production with 57 workshops known to have been operational in 1821. In the latter half of the 19th century there was a serious and sudden decrease in numbers, and by 1876, there were only 15 potters left. The very feature that had been the strength of the craft, both locally and regionally, and even internationally, the naturally heat-resistant clay, ultimately proved to be its downfall. The technical routine associated with the self-imposed isolation prevented the potters from becoming familiar with the latest developments in the business and, in particular, with new, rival materials. The latter were seen by consumers as more practical and hard-wearing. The failure to challenge their own economic model resulted in a lack of creativity and a failure to respond to market demands. They continued to produce their wares in the traditional way as best they could until the outbreak of the First World War.

Range of industrial ceramic products from Bonfol: pasta dish, lard pot, coffee pot, fondue skillet, oven-proof dishes, roasting dish, 1920-1950. Collection of the Fondation des poteries de Bonfol. Photo: OCC-SAP, Bernard Migy.

In the 20th century, production focused on factories with the range of products changing several times, which can probably be viewed as an attempt to adapt to market demands. Three enterprises were set up: the Fabrique de céramique Bregnard et Cie SA (1912-1957); the Fabrique Chappuis et Cie, which later became Céramique d’Ajoie SA (1924-1949) and the CISA SA (Céramiques industrielles SA, 1951-1999). However, mass production of utilitarian ware eventually went into decline in the late 1950s, despite the fact that CISA SA, a factory for floor and wall tiles, had only been set up in 1950, and a second enterprise employing highly skilled craftspeople with an artistic flair was taken over by Armand Bachofner on behalf of the CISA that same year. Both enterprises closed down in the 1990s (in 1991 and 1999 respectively).

Felicitas Holzgang, master potter and curator of the Pottery Museum in Bonfol, is now solely responsible for passing on the traditional craft. The cultural heritage associated with pottery production is safeguarded and maintained by the pottery museum (www.jurapoterie.ch).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Babey Ursule, Produits céramiques modernes. Ensemble de Porrentruy, Grand’Fin. Office de la culture et Société jurassienne d’Emulation, Porrentruy, 2003. (Cahier d’archéologie jurassienne 18). Accès en ligne : http://doc.rero.ch/record/21328?ln=fr

Emmanuelle Evéquoz et Ursule Babey, Rebeuvelier-La Verrerie, redécouverte d’un passé préindustriel. Office de la culture et Société jurassienne d’Emulation, Porrentruy, 2013. (Cahier d’archéologie jurassienne 35). Accès en ligne : http://doc.rero.ch/search?p=20190117172250-JE

Jonathan Frey, Court, Pâturage de l’Envers. Une verrerie forestière jurassienne du début du 18e siècle. Vol. 3: Die Kühl- und Haushaltskeramik. Berne, 2015.

Babey Ursule, Archéologie et histoire de la terre cuite en Ajoie, Jura, Suisse (1750-1900). Les exemples de la manufacture de faïence de Cornol et du centre potier de Bonfol. Office de la culture et Société jurassienne d’Emulation, Porrentruy, 2016. (Cahier d’archéologie jurassienne 37). Pour se procurer un exemplaire : https://www.jura.ch/fr/Autorites/Archeologie-2017/Publications/Les-cahiers-d-archeologie-jurassienne-CAJ.html