Andreas Heege, 2019

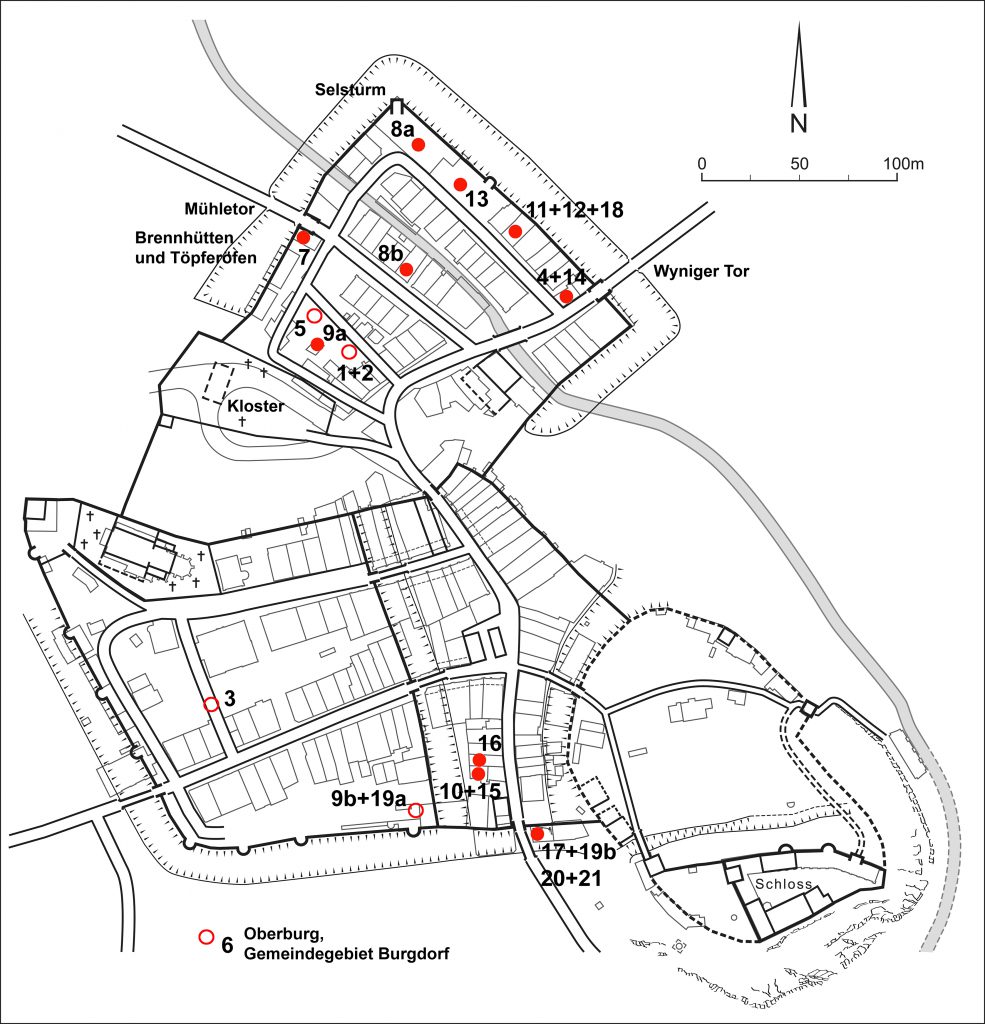

From the 16th century onwards, various potters began to set up workshops in Burgdorf and Oberburg (Fig. 1). They included Johannes and Jakob Vögeli, who, it has always been presumed, were father and son (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 195–199).

Fig. 1 Known locations of potters’ workshops in Burgdorf (see the list in the appendix)

For Burgdorf, as for the rest of the Canton of Bern, researchers mainly depend on stylistic criteria or on archaeological finds from potters’ workshops (wasters, waste dumps) when attributing objects to individual potters, as very few signed their wares in the 18th and 19th centuries. There are, however, a few exceptions to this rule.

Fig. 2 Water dispenser made by potter Johannes Vögeli from Burgdorf, dated 1707, w. 16.5 cm max. (base plate), 15.7 cm (cistern), h. 24 cm, d. 10.3 cm (base plate), 9.8 cm (cistern), (RSB Inv. IV-1026, photo A. Heege)

One exception is a water dispenser made by the Burgdorf potter Johannes Vögeli gifted to the Rittersaalverein association in 1923 (Fig. 2) (RSB IV-1060; first identified by Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 196 Fig. 230). Based on stylistic features, another series of ceramic objects could be added to the same group, which has allowed us for the first time to pinpoint some of the specific characteristics of this particular Burgdorf workshop. Another reason for compiling this summary of what we know at this point in time is that Trudi Aeschlimann has discovered numerous hitherto unknown documents referring to Johannes and Jakob Vögeli, which have shed new light on the previously posited kinship between the two men (the following statements are based mainly on documents in the citizens’ archive of Burgdorf (BAB): the baptismal register of parish priest Joh. Rudolf Gruner 1758 (BBB, MS HH VIII 33); genealogical lists of chronicler Joh. Rudolf Aeschlimann 1795 (BAB manuscript); the church registers of Burgdorf, especially the first register of deaths 1706–1726 in the state archive of Bern (StABE), KA 4 II, copies in the BAB; Burgdorf council manuals for the period between 1658 and 1719 (BAB); documents of the guild of smiths and carpenters (BAB).

The water dispenser has a green glaze on a coat of white slip, is box-shaped and has a rectangular cross section. Its walls have triangular crenellations at the top and a lid in the shape of a hipped roof with a reinforced ridge and hips. Two lugs (one missing) were originally used to hang the dispenser in a sideboard. The narrow sides and the front of the box have panels marked out by incised double lines. The front is decorated with two flowers (tulips?) with several blossoms. The left narrow side bears the motto “der dich Im guten Stand wol gmeind und hoch ge=Ehrt, Wüschen die Fus an dich, wann du Bist umb gekehrt – Those who revere you when you are doing well will wipe their feet on you when you are not”. The right narrow side has the potter’s mark and the date: “den 4ten Aprellen Anno 1707 Johannes Vögeli haffner in Burgdorff” [4th April 1707 Johannes Vögeli potter in Burgdorf]. The broad sides of the lid also have mottos: “Thu das, weil du noch bist gesund, was du wünschest zur Sterbens Stund” [while you are still in good health, do what you hope to have achieved by the time you die] and “Wann Irgend einer wär, der könt den tod vertreiben, so würden gar Leüt, auff erden Lebend Bleiben” [if someone could banish death, people would live on this earth forever]. The left side of the lid again bears the date “den 4ten aprellen” [4th April] and the right side also bears the initials “HV” [Hannes Vögeli].

The fact that Johannes Vögeli signed his name attests to his self-confidence, which was rather unusual for a potter of that period. The way the letters and numbers were executed and the fact that small diamond shapes were used to separate words was quite distinct. Because only boys learned to write in the Canton of Bern in the 18th century (cf. Heege/Kistler/Thut 2011, 144 and 154), we can assume that Johannes Vögeli’s ceramics were inscribed by himself and the job was not left to an unskilled assistant. Vögeli was the first potter in the Bern region to incise lengthy mottos on his plates. The literary sources that may have inspired these sayings are at this point in time unknown. We can only assume that he modelled his mottos on products from Winterthur, which bore inscriptions such as these as early as the beginning of the 17th century (Wyss 1973; Schnyder 1989). In the early 18th century mottos in the Bern region were also sometimes added in underglaze brushwork, though no complete pieces survive in museum collections today (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 138–143).

So who was Johannes Vögeli?

He was baptised on 21st March 1642. His grandfather Hans/Johannes (1585–1651) and his father Jakob (1613–1696) were both ropemakers and burghers of Burgdorf. In 1659, Johannes too was accepted into the burgher community and became a member of the guild of smiths and carpenters. On 4th August 1662 he married Catharina Leeman. The marriage remained childless.

An entry in the minutes of a Burgdorf council meeting from 4th June 1659 reads: “The potter Johannes Vögeli is permitted to install a potter’s kiln in his father’s residence similar to the one described to the gentlemen who carried out the inspection, but the permit is at the discretion of the inspectors.” (RM 45 1658–1662, p. 31). The entry proves that Johannes, at the age of 17 and just after becoming a burgher, set up a potter’s workshop with a kiln in his parents’ house, and it is therefore no surprise that he also begins to appear in Bernese annual accounts for Burgdorf after 1660/61 (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 194 fn. 1122). Unfortunately, the workshop’s exact location is unknown.

Over the coming years Johannes’ kiln would be a constant source of trouble. In July 1663, for example, the council minutes recorded an incident where flames had shot out of the approved kiln of potter Johannes Vögeli, much to the horror of his neighbours. Vögeli stated that he had only fired large vessels and no small ones. He was warned to be more careful in future. A similar incident was recorded in April 1667 (RM 46 1663-1666. p. 41; RM 47 1666-1669, p. 66). In 1673, Vögeli was even forced to suspend alteration and renovation works on a potter’s kiln on his premises because his neighbours had complained to the council about the potential fire hazard. The council eventually decided, “That he should repair the potter’s kiln in his mother’s (Verena Venner [author’s note]) house.” He was also ordered to pay for all damages incurred (RM 49 1672–1676, p. 83, 84).

Quarrels about the locations of potters’ kilns, which were considered fire hazards, often occurred in Burgdorf, not just with regard to Johannes Vögeli. In 1683, for example, the potter Oswald Schönberger (born in 1642) threatened to leave Burgdorf and abandon his wife and children if he was not offered a location for his kiln other than the monastery. He was subsequently permitted to “build a potter’s kiln in the Graben (ditch)” (RM 51 1679-1684, p. 267. The monastery would have been a Franciscan Friary between the Oberstadt and Unterstadt areas of the town; for more information on the location see Baeriswyl 2003, Fig. 25). Perhaps Graben referred to a site adjacent to the Mühletor gate, as Oswald Schönberger was one of a number of people affected by a fire in the Unterstadt area in 1715. In 1697, Schönberger was once more refused permission to build a kiln in the ditch adjacent to the curtain wall (RM 56/57/58 1696-1698, p. 146). In 1690, potter Bendicht Gammeter (born in 1648) applied for permission to build a new kiln near his home “in the ditch in front of the lower gate” (=Wynigentor gate). His bid, however, was unsuccessful due to objections lodged by his neighbours. The council eventually allowed him to build a kiln in his own home, provided it would not endanger the neighbourhood (RM 53 1687-1690, pp. 178, 189 and 190, 200). There were no further complaints about Johannes Vögeli’s workshop for the next 30 years, but in 1703 he had to once again answer questions for “firing too hard”. He stated that his journeyman had overstoked the fire, and apologised to the council (RM 62a 1702-1709, p. 77).

The records for 1676 show that Johannes Vögeli had to contribute two batzen coins a week towards the salary of potter Jakob Knup junior from Oberburg (died in 1690) to support Knup’s wife and three children. This means that Knup worked in Vögeli’s workshop (RM 50 1676-1679, p. 7. Various other references to the Oberburg potters Jakob Knup senior, Jakob Knup junior and Hans Knup can also be found in the records of the smiths’ guild 1673–1700 and in the accounts of the smiths’ guild, c. 1686/1691–1713). Based on entries in the accounts of the smiths’ guild (c. 1686/1691–1713) we can see that Johannes Vögeli trained apprentices, although the entries are unfortunately undated. By 1677 his work must have been of such a high standard that he received a public commission. He was paid 20 kronen along with tips for setting a new tiled stove in the rear council chamber (RM 50 1676-1679, p. 96; Schweizer 1985, 269). Between 1689/90 and 1697/98 Johannes Vögeli’s work also appears in the Bernese financial records for the Bailiwick of Brandis (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 194 fn. 1122).

From 1680 to 1684, Johannes served as an “Iseler”, an inspector of weights and measures (RM 51 1679-1684, p. 75). As a member of the Council of 32, he held the office of “Einunger” from 1684 to 1688 (RM 52 1684-1687, p. 115; RM 53 1687-1690, p. 65, last Einunger accounts submitted by the potter Johannes Vögeli). Similar to an municipal police officer, an “Einunger” supervised forestry and timber royalties. In 1702, at the age of 60, he married his second wife, Magdalena Matter. The couple’s son Johann Christian was baptised on 14th October 1703.

Although it was rather unusual for a potter to obtain a council seat, Johannes Vögeli managed nevertheless. As a member of the Council of 32, he was elected church steward, i.e. church treasurer, for a five-year term from 1705 (RM 62a 1702-1709, p. 383; RM 65, 1709-1714, p. 180).

In 1706, Johannes Vögeli’s journeyman was awarded a “Discretion” for his bravery during a blaze in the Oberstadt area of Burgdorf (on the Oberstadt fire of 1706 see Schweizer 1985, 242–244). Vögeli himself distributed “several pieces of earthenware vessels” to each affected household (Aeschlimann 1847, 194).

The records of 1706 include a quarrel between the church steward and master potter Johannes Vögeli and the potter Bendicht Gammeter. Gammeter had been commissioned by the mayor to fit a tiled stove in the sexton’s house (on Kirchbühl/Beginengässli lane). The fact, however, that the stove was eventually set by Vögeli, was deemed by the council to be appropriate, as the care of stoves and windows was part of the official remit of the church steward (RM 62a, 1702-1709, p. 571).

The records of the smiths’ guild contain another reference to Johannes Vögeli on 26th December 1712. It states that Vögeli has been declared “exempt from attending funerals due to his advanced age (at 70!) and his physical frailties, in exchange for 5 batzen coins”. He was ordered “however, to attend the masters’ meetings whenever possible, or else he will have to pay a fine of 1 pound” (Meisterbuch der Schmiedenzunft 1701–1766, p. 87). Unfortunately, there is a gap in the Burgdorf register of deaths for the years 1713 and 1714, which means that it is not known exactly when Johannes Vögeli died. According to the town’s chronicler Joh. Rudolf Aeschlimann, however, he was predeceased by his son (Genealogien von Chronist Joh. Rudolf Aeschlimann 1795, 553ff.). Nor do the records mention him as one of those affected by the Unterstadt fire in 1715 (cf. Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995, 76). Based on the information that has come to light so far, we can assume that Johannes Vögeli’s period of production lasted from 1659 until no later than 1714.

Fig. 3 Paperweight from Johannes Vögeli’s workshop, dated 1669, max. diam. 10.9 cm, max. h. 10 cm (photo BHM Inv. 2091, A. Heege)

The features observed on the water cistern of 1707 described above allow us to attribute a series of ceramic objects from Swiss museums and private collections to Johannes Vögeli or to his workshop. The earliest dated piece is a paperweight from a Burgdorf household bearing the year 1669 and the typical small diamond shape (Fig. 3).

Fig. 4 Tankard, dated 1672, green glaze on the outside, yellow glaze on the inside, rim diam. 8 cm, h. 14.3 cm (photo BHM Inv. 20728, A. Heege)

A tankard dated 1672 was acquired from an antique dealer called Schumacher in Langenthal in 1930 (Fig. 4). The style of the date and the small diamond are again features that allow us to attribute it to Vögeli.

Fig. 5 Plate, dated 1677, rim diam. 37.1 cm, h. 8.1 cm (photo BHM Inv. 5076, A. Heege)

An exceptional piece from the workshop of Johannes Vögeli is a plate bearing the date 1677 (Fig. 5). It is the oldest known object in the Canton of Bern and has combed decoration in red and green on its rim and well. It is also the oldest known piece bearing a motto. It reads “The mother loves her children and they love her in turn, so that what has God ordained comes about both ways”. The plate was acquired in Montreux in 1903.

Fig. 6 Wash basin, dated 1696, back plate max. w. 41 cm, back plate max. h. 18 cm, basin max. d. 34.8 cm, basin front h. 8.2 cm (RSB Inv. IV-209, photo A. Heege)

The next examples follow a hiatus of almost 20 years. They include a wash basin or lavabo dated 1696 (Fig. 6), donated to the Rittersaalverein association soon after its establishment by the Burgdorf veterinarian Isel (published previously by Boschetti-Maradi 2006, Fig. 144). In the 17th and 18th centuries, such basins and water dispensers usually came in a matching set. The piece presented here has a green glaze on a coat of white slip both inside and out, its back wall is straight and higher than the rest of the basin to protect the wall from water splashes, making the piece suitable for fitting inside a closet. Two massive handles made it portable so that the dirty water could be disposed of. The rim of the back plate bears the motto “a friend here, a friend there, everywhere, if I had nothing, who would help me”. The date on the front reads “on the 15th of the winter month in the year 1696”.

Fig. 7 Onion pot, dated 1696, rim diam. 13.3 cm, h. 19,6 cm (RSB IV-618, photo A. Heege)

This onion pot, sold to the museum by clockmaker Henzi from Burgdorf in c. 1900, also dates from 1696. It can also be attributed to Johannes Vögeli’s workshop based on the style of its incised date (Fig. 7). It has a green glaze on a white coat of slip and two lugs, one on either side, for suspension in a warm kitchen. Filled with small onions and soil at Martinmas, it would have sprouted green shoots by Christmas, which could then be used in the winter and spring months to add to soups as an alternative to chives.

Fig. 8 Fragments of an onion pot from an excavation carried out on Kornhausgasse lane in the Unterstadt area of Burgdorf. The pot probably came from Johannes Vögeli’s workshop (ADB, photo Badri Redha).

Another onion pot was found in an excavation on Kornhausgasse lane in Burgdorf (Fig. 8). Based on its shape and a single incised number from a date, it may also be attributed to the same group of objects (ADB Fnr. 45768).

Fig. 9 Water dispenser, dated 1699, surviving w. incl. handle 22 cm, h. 16 cm, d. 10 cm (SNM Inv. 8243, photo Donat Stuppan)

Based on its shape and incised decoration, a water dispenser which is kept at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich probably also came from the Vögeli workshop (Fig. 9, cf. Fig. 2). It has a green glaze on a coat of white slip and is dated 1699. The front is decorated with a typical floral pattern enclosed in a double-lined frame. The incised inscription is difficult to read but it probably consists of a name and a date: “Melcker Wittewer (?)” and “Jener Lest Tag 1699” (possibly meaning last day of January 1699?). The flow of the writing is not as skilful as we have come to expect from the Vögeli workshop. Could this be the handwriting of a journeyman or apprentice?

Fig. 10 Plate, dated 1696, rim diam. 38 cm, h. 8 cm (FMST Inv. K157, photo A. Heege)

A private collection in Bern contains two plates bearing the characteristic writing and matching decorations, one bearing the date 1696, the other 1701 (Figs 10 and 11). The earlier plate has a green glaze on its inside only and bears a vegetal incised pattern on its well that is rather casually executed. The inscriptions on the lip are divided into two lines. The mottos read: “No man is as bold and brave that he wouldn’t lose courage if he was admonished and reminded that he has acted to his parents’ shame” and “If leaves and grass grew like envy and hate, the horses and cattle would have a good winter this year”. The date on the plate reads “9th January in the year 1696” (previously published by Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 98 Fig. 122).

Fig. 11 Plate, dated 1701, rim diam. 26 cm, h. 4.5 cm (FMST Inv. K122, photo A. Heege)

The plate from 1701 (Fig. 11) has a green glaze on a coat of white slip both inside and out. The well bears a rosette and the date “the 2 7ber in the year 1701” [7ber = September]. The lip is inscribed with two lines of mottos: “Say what you can stand over, the truth must permeate all, lies will be upbraided by everyone, so speak only what can be believed, 1701” and “If there was someone who could cast out death, there would be far too many people on this earth”.

Fig. 12 Plate, dated 1702, rim diam. 29 cm, h. 7 cm (private ownership, photo A. Heege)

Another plate from 1702 has survived in a private collection in the French-speaking part of Switzerland (Fig. 12). It has a very thin green glaze on a coat of white slip both inside and out. Its well is decorated with an incised flower. The mottos and a date are arranged in two lines on the lip: “The rich man should bear in mind that life on earth is not everlasting, and should in his time behave in such a way that he might live on in eternity, the 17th April in the year 1702” and “Those who wish to write poetry, and whose mind is set on art, favour, honour and property, once they attain them, they will lie down and die”.

Fig. 13 Shaving basin, dated 1709, rim diam. 26.8 cm (SNM Inv. LM-45041, photo Donat Stuppan)

A shaving basin dated 1709 with a yellow glaze on a white coat of slip both inside and out is an object that is not often found (Fig. 13). The cutout in the lip was to make it more comfortable to hold it against one’s neck while being shaved. The basin has a lug on the back so that it could be hung on a wall for decorative purposes. The well, again, has a typical incised flower and the date 1709. The central motif is encircled by a wreath of flowers. The lip bears two mottos arranged in two lines: “Say what you can stand over, the truth must permeate all, lies will be upbraided by everyone, so speak only what can be believed” and “He who thinks of me, will not think of himself, for if he thought of himself, he would forget me. 23rd August”.

Fig. 14 Wash basin, dated 1710, max. w. 34.5 cm, max. d. 28.6 cm, max. h. 19.5 cm (SNM Inv. IN-137.22b, photo Donat Stuppan)

Closely related from a stylistic point of view to the wash basin of 1696 (see Fig. 6) is another basin dated 1710 (Fig. 14). It is housed today at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. Based on its shape and the style of the incised flower and date on the back, it can be attributed to the Vögeli workshop.

Fig. 15 Tureen with external lid seating and cover, dated 1683, (MKB Inv. 1908-65, photo A. Heege)

With its unusual decorations, this tureen with external lid seating and cover (Fig. 15) is more difficult to classify. It is dated 1683 and according to its inscription was dedicated to “Maid Anmaria Zender” (reference to this piece was also made by Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 117 Fig. 150). It is lavishly adorned with stamped decoration and chip-carved stars. A piece of mirror glass is set into the top of the lid. The incised decoration in the bottom of the bowl and inside the lid, on the other hand, are of the style that we have become accustomed to from the Vögeli workshop. Similar tureens with external lid seatings and lug handles in the shape of putto heads have also been found in the rubble from the Unterstadt fire in Burgdorf which occurred in 1715 (ADB, Fnr. 39791 from layer 103). This may be seen as additional evidence to show that they were made in Burgdorf.

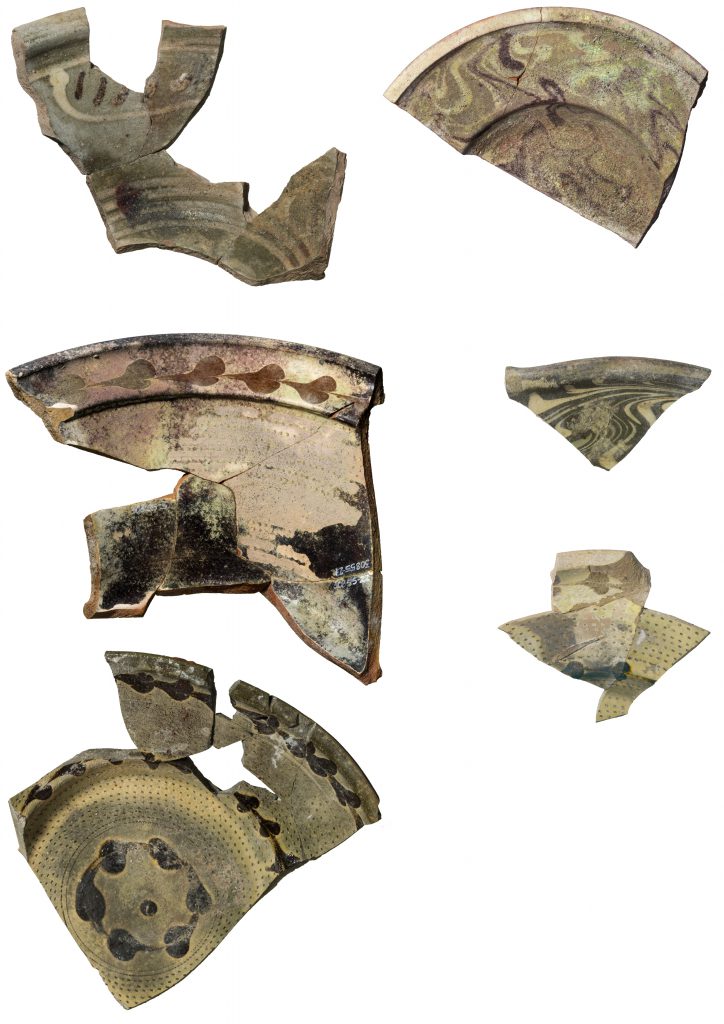

Fig. 16 Archaeological finds of ceramic fragments from Burgdorf, which can be associated with Johannes Vögeli. Top section Kornhausgasse 9-11, excavation 1992; second row from bottom Kronenhalde nursery school, excavation 1991; bottom row Kornhaus, excavation 1988/1989 (photo ADB, Badri Redha)

So far, three archaeological sites have brought to light pottery from the workshop of Johannes Vögeli. They were all located in the Unterstadt district of Burgdorf, in the area of the row of houses on 9-11 Kornhausgasse lane, in the burnt and levelled rubble from the 1715 fire in the Unterstadt area beneath the Kornhaus building and adjacent to the newly built Kronenhalde nursery school outside of the Wynigentor gate (Fig. 16) (ADB, Fnr. 46103, Kornhausgasse 9–11; 26870, 26876, 30877, 32305, 39782, Kornhaus, 39770, Kindergarten Kronenhalde). The writing and the incised floral patterns on these finds undoubtedly support their association with Johannes Vögeli. An important feature, particularly in view of the pottery presented below, is that the only other type of decoration that has ever been found in conjunction with Vögeli’s incised designs was combed decoration, while other techniques, e.g. chattering were absent. So far, his pottery has not been found anywhere other than Burgdorf.

Given the high quality of Johannes Vögeli’s products, it is very unfortunate that we do not know where his workshop was located. We can only assume that it was somewhere in the Unterstadt district of Burgdorf, probably near the Mühletor gate or perhaps on Röhrlisgasse, a lane that became disused after the fire of 1715 (pers. comm. Trudi Aeschlimann. On the location see Schweizer 1985, 387 Fig. 330; Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995, Fig. 69).

The potter Jakob Vögeli (1680-1724)

The opposite applied to the workshop of potter Jakob Vögeli, which was destroyed during the Unterstadt fire of 1715. Jakob Vögeli was baptised on 9th May 1680. He died on 31st March 1724 (Totenrodel 1 von Burgdorf 1706–1726, with gaps, p. 489). His ancestors had lived in Burgdorf since the 16th century and mainly consisted of shoemakers, butchers and ropemakers. Despite sharing the same name, this family, intriguingly, was not related to the branch that Johannes Vögeli descended from. In 1696, Jakob Vögeli began his apprenticeship with Hans Knup (poss. 1647–1715) in Oberburg (RM 55 1694-1696, p. 214; also BAB T9, Zinsrodel der Schmiedenzunft, undated entry, around 1696), after which he embarked on his journeyman’s travels, though it is not known where they took him. An entry of 20th June 1706 in the book of master smiths notes that Jakob Vögeli requested a certificate for his apprenticeship and journeyman’s years. “It is hereby certified that he has learnt the potter’s craft as is right and proper, that he has completed his journeyman’s years, and that he has complied with the statutory regulations as per his age, as certified by this note” (BAB T2, Meisterbuch der Schmiedenzunft 1701–1766, p. 63). Only six days later, he was also made a burgher and a member of the guild of smiths and carpenters (RM 62a, 1702-1709, p. 491). In 1707 he married Barbara Trechsel from Burgdorf.

Together with the conferral of burghership, the council minutes also stipulate that “He shall not build a potter’s kiln, he will be allocated a site for this purpose by my lords”. Jakob Vögeli appears to have begun producing his wares immediately afterwards, as he was one of those who helped to rebuild the Oberstadt area after the fire of 1706. In December (probably of 1708), he fitted a new tiled stove for coppersmith Johannes Stähli at 10 Schmiedengasse lane, charging him 10 kronen and 4 batzen (list of rebuilding costs in the Rittersaalverein Burgdorf RSB, Inv. RS X 214, see also: Schweizer 1985, 244). It is not clear where Vögeli fired the tiles for this stove, as there were protracted disputes over the building site for his workshop and kiln. On 15th December 1706 he was permitted to “build a kiln hut in the town moat outside of the Wynigentor gate on the left-hand side along the outermost corner of the wall”. It was stipulated that there must be no threat to neighbouring properties. At the same time Vögeli had to promise that if any of the other burghers’ sons ever wished to train as potters, he would make his kiln available to that apprentice. On 9th April 1707 he was allocated the timber required to build his hut, but on 13th April his building site was moved to the ditch at the lower tower, known as Selsthurm (tower in the north-western corner of the Unterstadt fortifications). Vögeli, however, was not happy with this site, and on 27th February 1708, the council nominated two of its members to allocate another site in the moat outside the Mühletor gate to him. Here, too, Jakob Vögeli appears to have protested, and in the end he was granted his wish: on 14th April 1708, he was given permission to build the kiln in his own house, with the proviso, however, that he install it in such a way that it would pose no fire risk. Also, he, like all other potters in Burgdorf, would not be allowed to fire his wares at night-time (RM 62a, 1702–1709, pp. 591, 593, 665, 671, 780, 793).

It seems that Jakob Vögeli was not as easy to deal with as his colleague, Johannes Vögeli. On 1st August he was fined for procuring wood unlawfully (RM 65, 1709-1714, p. 301). Despite this, he was given public commissions, for example to carry out work at “my lord’s new house on Schmiedegasse lane” or at the Wasenmeisterhaus (knacker’s house) (RM 65, 1709-1714, p. 371). In April 1713, Jakob Vögeli was taken to task for “improper behaviour” (RM 65, 1709–1714, p. 558). Because his kiln was said to pose a fire risk, the council arranged an inspection to take place on 2nd May 1715; unfortunately, the outcome is unknown (RM 66, 1714-1720, p. 100). Because Vögeli was once again found to have committed offences against forest laws when building a pigsty and for the use of foul language, he was put in jail for 24 hours (RM 66, 1714–1720, p. 120).

On 14th August 1715, a fire broke out in the “rear house” of potter Heinrich Gammeter on Röhrlisgasse lane (fire damage incident no. 7), which reduced large parts of the Unterstadt area to ashes (on the Unterstadt fire of 1715 see Aeschlimann 1847, 199–200; Schweizer 1985, 386–406; Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995, 74–77; Baeriswyl 2003, 62–78; Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 67–70). In this context, the records also state that two years previously, Gammeter had his” kiln hut outside of the town at Kreutzgraben ditch”, i.e. outside the town walls (RM 66, 1714-1720, p. 148).

Jakob Vögeli was one of those affected by the fire (fire damage incident no. 15). The paperwork relating to this allowed us to pinpoint his residence and potter’s kiln. The house was worth 550 pounds and was located directly beside the Unterstadt town wall beneath the Kornhaus granary built in 1770 (cf. Fig. 1,8a); the site was excavated in 1988/1989 (Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995, 76).

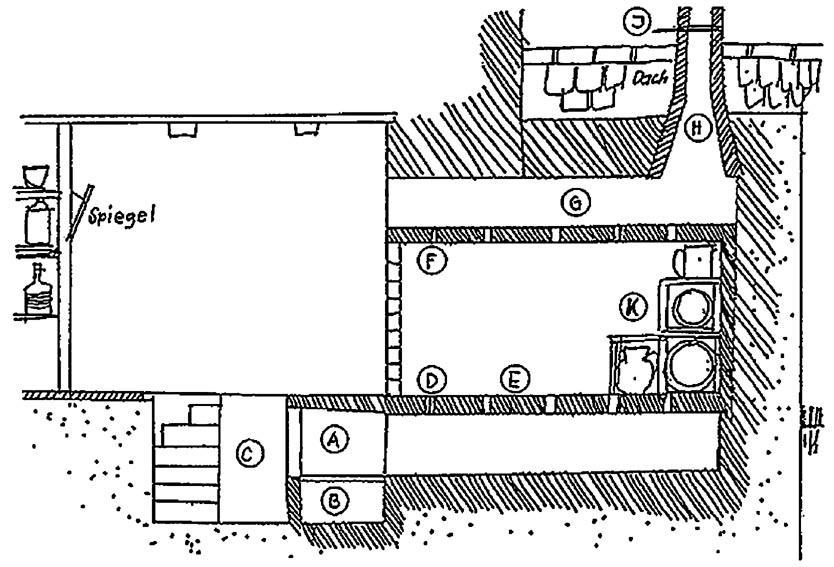

Fig. 17 Remains of Jakob Vögeli’s potter’s kiln. The stoke hole is in the foreground, with the combustion chamber behind it. The actual firing chamber would have been above that and has not survived. The kiln was destroyed by the Unterstadt fire of 1715 and subsequently levelled. (photo ADB)

The kiln (Fig. 17), known as a “Piccolpasso” type kiln, was rectangular in shape and built flat directly onto the floor of the workshop. It was wood-fired and was the kiln of choice for potters in the German-speaking part of Switzerland from the 16th to the 20th century.

Fig. 18 Longitudinal section of a typical Bernese potter’s kiln of the Piccolpasso type. (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, Fig. 48).

This type of kiln has a slightly protruding stoke hole, a combustion chamber that is separated from the firing chamber above by a suspended floor with perforated vents, a separate smoke dome and a chimney for the smoke and gasses to escape (Fig. 18).

Fig. 19 Kiln furniture from the burnt rubble around Jakob Vögeli’s workshop beneath the Kornhaus granary in Burgdorf. (photo ADB, Badri Redha)

Because the burnt rubble from Vögeli’s house and all its neighbouring buildings along the town wall were obviously searched systematically and the whole area was subsequently levelled, only a small number of props can be attributed to Jakob Vögeli’s workshop with any degree of certainty (Fig. 19). Kiln furniture of this type was used to stack the vessels in the potter’s kiln before firing.

Fig. 20 Biscuit-fired onion pot recovered from the burnt rubble around Jakob Vögeli’s workshop beneath the Kornhaus granary in Burgdorf. (photo ADB, Badri Redha).

Some of the unglazed vessels or biscuit-fired objects may also have been made in his workshop. This included a so-called onion pot (Fig. 20). All the other finds could either have come from Vögeli’s workshop or could simply have been some of the normal household items or domestic waste left behind by his neighbours. All we can say for certain is that all the burnt pottery dated from the period before 14th August 1715.

Fig. 21 Burnt pottery from the rubble in the area of the workshop. Some of Jakob Vögeli’s products perhaps? (photo ADB, Badri Redha).

This is where we can make an interesting observation when we compare the wares of one Vögeli to those of the other (Fig. 21). While Johannes Vögeli used combed decoration, Jakob now added all-over marbled decoration and polychrome slip-trailing. Chattering also appeared for the first time, though it had already been developed over a century earlier in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. With the exception of a small number of pieces from Winterthur, this is the earliest evidence of the technique being used in the German-speaking part of Switzerland; it had not previously been known in the Canton of Bern (on the technique and its origins see Heege 2016, Chap. 4.1). The obvious assumption would be that Jakob Vögeli had picked it up on his journeyman’s travels in Germany.

Following the town fire, Jakob Vögeli built a new home at no. 10 Mühlegasse lane in the Unterstadt area of Burgdorf (cf. Fig. 1,8b; Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995, 76; RM 66, 1714–1720, p. 368). We can probably assume that his workshop was located on the same site. He was involved in rebuilding the Mühletor gate and the gate warden’s accommodation in 1716/1717 (Schweizer 1985, 39). In 1719, we are told of another altercation with his neighbour Maria Trechsel (Mühlegasse 8), who owed Vögeli half a krone for work on a stove (RM 66, 1714-1720, p. 785).

Jakob Vögeli was only 44 when he died on 31st March 1724, though the cause of death was not recorded (Totenrodel 1 von Burgdorf 1706–1726, p. 489). His death brought pottery making to an end at 10 Mühlegasse lane, as his son and heir, Jakob Vögeli-Flückiger (1710–1778) was a tailor (pers. comm. Trudi Aeschlimann). Based on the dates of Jakob senior’s birth and death, we can assume his period of production to have been between 1706 and 1724.

Summary:

The potter Johannes Vögeli (1642–c. 1714) was the son of a ropemaker from Burgdorf, and appears to have been a successful, well-connected and reputable potter, who rose to become a member of the Council of 32 in Burgdorf and at various different times also held the offices of “Iseler” (inspector of weights and measures), “Einunger” (overseer of forestry and timber royalties) and “Kirchmeier” (church steward). A small group of pottery products can be firmly attributed to his workshop based on characteristic inscriptions. Some were found during archaeological excavations in Burgdorf. His pottery is characterised by numerous incised mottos and dates and the occasional use of combed decoration. Until his workshop is found, we can only speculate as to whether he also made everyday ware with minimal decoration, which would have been quite difficult to tell apart from the products created by other potters in Burgdorf or Bern. What we do know is that Johannes Vögeli also produced and set tiled stoves, though we do not know what the tiles looked like or how they were decorated.

The potter Jakob Vögeli (1680–1724) also came from a Burgdorf family of ropemakers, but the two families were not related. Following an apprenticeship in Oberburg and a period of travel as a journeyman, he began to work in Burgdorf as a potter and stove setter in 1706. His products cannot be distinguished beyond doubt from other potters’ wares. There is a theory, however, that he perhaps encountered chattering as a decorative technique on his journeyman’s travels around Germany and brought it back to Burgdorf, where it would play a major role particularly in the production of Langnau ware in the 18th century.

All genealogical and biographical information was collected by Trudi Aeschlimann, Burgdorf, and I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to her for all her help and encouragement in writing this article.

First published:

Heege 2015

Andreas Heege, Die Hafnereien Vögeli in der Burgdorfer Unterstadt, in: Burgdorfer Jahrbuch 83, 2015, 41-68.

Potters’ workshops in Burgdorf (key to Fig. 1)

1 + 2 Röhrlisgasse, Jakob Knup junior and senior, mentioned between 1689 and

1699

3 Beginengässli West, potter Johannes Dübelt’s widow, Oberstadt fire 1706

4 Metzgergasse 4, until 1712 Bendicht Gammeter, after 1712 his widow K. Ris

14 Metzgergasse 4, around 1746 Heinrich Gammeter “other” potter

5 near untere Mühle/ Röhrisgasse, until no later than 1714 Johannes Vögeli

6 probably Chnuppenmatt (Post) Oberburg, actually municipality of Burgdorf,

the Burgdorf potter Hans Knup, mentioned between 1688 and 1715

7 at the Mühletor gate/town moat, Oswald Schönberger, mentioned between

1683 and 1719

8a “below” the Kornhaus granary, 1708-1715 Jakob Vögeli

8b Mühlegasse 10, after 1715 Jakob Vögeli

9a Röhrisgasse, until the 1715 fire Heinrich Gammeter

9b Milchgässli (west upper Badstube), Heinrich Gammeter, mentioned in 1746

19a Milchgässli (west upper Badstube), Emanuel Aeschlimann, mentioned after

1775

10 Hofstatt 7, “Gammeterhaus”, Jakob Gammeter-Flückiger, mentioned between

1737 and 1754

15 Hofstatt 7, Joh. Jakob Gammeter-Aeschlimann senior, mentioned between

1754 and 1800

11 Hintere Gasse (Kornhausgasse) 10, Samuel I Gammeter, mentioned between

1746 and 1758

12 Hintere Gasse (Kornhausgasse) 10, Samuel II Gammeter, mentioned between

1758 and 1761

18 Hintere Gasse (Kornhausgasse) 10, Rudolf Samuel Gammeter, mentioned in

1800

13 Hintere Gasse, next to the later Kornhaus granary, Johann Heinrich Gammeter

jun. rented the potter’s hut from 1759 to 1770 (see the Aeschlimann plan of

1773)

16 Rütschelengasse 6/Hofstatt 5, Joh. Jakob Gammeter son, mentioned in 1800

19b Rütschelengasse 23, near the gate, from around 1795 to 1832 Emanuel

Aeschlimann

17 Rütschelengasse 23, until 1828 Joh. Heinrich I Aeschlimann

20 Rütschelengasse 23, until 1866 Heinrich II Aeschlimann

21 Rütschelengasse 23, until 1908 Joh. Arthur Aeschlimann “utility pipemaker”

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Aeschlimann 1847

Johann Rudolf Aeschlimann, Geschichte von Burgdorf und Umgegend, Zwickau 1847.

Baeriswyl 2003

Armand Baeriswyl, Stadt, Vorstadt und Stadterweiterung im Mittelalter. Archäologische und historische Studien zum Wachstum der drei Zähringerstädte Burgdorf, Bern und Freiburg im Breisgau (Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters 30), Basel 2003.

Baeriswyl/Gutscher 1995

Armand Baeriswyl/Daniel Gutscher, Burgdorf Kornhaus, Eine mittelalterliche Häuserzeile in der Burgdorfer Unterstadt (Schriftenreihe der Erziehungsdirektion des Kantons Bern), Bern 1995.

Boschetti-Maradi 2006

Adriano Boschetti-Maradi, Gefässkeramik und Hafnerei in der Frühen Neuzeit im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 8), Bern 2006.

Heege 2016

Andreas Heege, Die Ausgrabungen auf dem Kirchhügel von Bendern, Gemeinde Gamprin, Fürstentum Liechtenstein. Bd. 2: Die Geschirrkeramik des 12. bis 20. Jahrhunderts, Vaduz 2016

Heege/Kistler/Thut 2011

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler/Walter Thut, Keramik aus Bäriswil. Zur Geschichte einer bedeutenden Landhafnerei im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 10), Bern 2011.

Schnyder 1989

Rudolf Schnyder, Winterthurer Keramik, Winterthur 1989.

Schweizer 1985

Jürg Schweizer, Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Bern, Land, Bd. 1, Die Stadt Burgdorf (Die Kunstdenkmäler der Schweiz 75), Basel 1985.

Wyss 1973

Robert L. Wyss, Winterthurer Keramik. Hafnerware aus dem 17. Jahrhundert (Schweizer Heimatbücher 169-172), Bern 1973.