Pottery made by Johann Martin Labhardt in the image database

Andreas Heege, Andreas Kistler 2019

It is not known why, on 1st May 1842, Samuel Herrmann (1797–1845, Langnau, atelier 5, style 17c?) sold the property at 5 Wiederbergstrasse in Langnau with all its assets and liabilities to Peter Herrmann (1809–1871), the eldest of four sons of Peter Herrmann senior (1785–1840) from the workshop at 1 Höheweg. This was when Peter Herrmann junior became self-employed (see Langnau, Herrmann family tree). No known objects can be attributed to the workshop until 1853, when the journeyman Johann Martin Labhardt from Steckborn in the Canton of Thurgau began to work there (Langnau, atelier 6, style 22). Johann Martin Labhardt’s dates of birth and death have so far remained elusive (cf. Früh 2005, 532, although it is not clear if this reference applies to him or to one of his relatives).

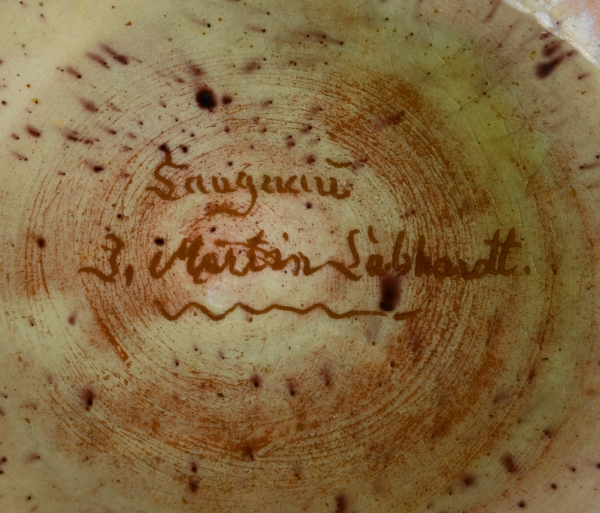

Before joining Peter Herrmann’s workshop, i.e. from 26th January 1849 to 29th April 1853, Labhardt had worked for Johannes Krähenbühl (1828–?) at his workshop at 30 Dorfstrasse in Langnau (StAB Bez Signau B 19. GAL 671). It is possible that this was where the rather unusual tureen pictured above was made; signed by Labhardt, its garland of flowers and leaves is unmistakably rooted in the region of Heimberg-Steffisburg and not in Langnau (MAHN AA 2055). However, it could also have been made at Peter Herrmann’s workshop or even at that of Johannes Herrmann (1802–1867) at 1 Sonnweg, another of Johann Martin Labhardt’s workplaces between November 1853 and October 1854, at which time he left Langnau permanently.

The tureen (MAHN AA 2055) is decorated with an unusually large number of mottos, none of which are known to have been used in Langnau: “Wenn dich die Lästerzunge sticht, so lass es dir zum Troste sagen, die schlechtesten Früchte sind es nicht, woran die Wespen nagen. Alles in der Welt lässt sich ertragen, nur nicht eine Reih, von schönen Tagen.” (“When you are stung by detractors, take comfort in the knowledge that it is not the poorest fruits that attract the wasps. Everything can be endured in life, except for a series of fair-weather days.”) The motto on the edge of the lid reads: “Frisch und fröhlich, fromm und ehrlich, frei von Gemüth, ehrlich von Geblüt, diese Tugend, ziehrt die Jugend. // Vorgethan und nachgedacht, hat manchen in groß Leid gebracht.” (“Fresh and cheerful, pious and sincere, free of spirit, true of blood, these are the virtues that adorn the young. // Acting first and thinking later has brought much regret to many.”) The handle on the lid, finally, reads: “Rede wenig, mach es wahr, borge wenig, zahl es baar, sagt ein Sprichwort.” (“Say little, let your actions do the talking, borrow little, pay it back in cash, so the proverb goes.”). The first motto was put together from two different sources. In 1787, Gottfried August Bürger (1747–1794), a German poet from the period of the Enlightenment and translator and author of “The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen”, published a poem called “Trost” (Solace) in the Göttinger Musenalmanach, a collection of poems, which included the passage referring to the detractors. The second part was taken from a collection of Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s poems published in 1815, which included the motto under the heading “Sprichwörtlich” (Proverbial). No literary references could be found for the mottos on the edge of the tureen and below the handle of the lid, except folkloristic sources like building inscriptions in the Alsace region. Nevertheless, the quotes shed light on Johann Martin Labhardt’s erudition and education and show how well he knew his Goethe.

This can also be seen in an unusual and rather special butter churn which, according to its signature, was made by Johann Martin Labhardt at the workshop of Peter Herrmann (1809–1871) (FWMC C.1911-1928). Unfortunately, the date was erased at some stage, but the year 1853 can just about be deciphered. The butter churn BU 7 has the old-style recessed handle 2 which can be attributed to “atelier 3, styles 5, 6 and 8” from between 1781 and 1825. It is therefore possible that Peter junior (1809–1871) inherited the mould from his father, Peter senior (1785–1840) and took it with him when he opened his new workshop at 5 Wiederbergstrasse.

The decoration on the butter churn had several novel features, which did not exist in Langnau prior to that time. Firstly, the coat of white slip was applied over a coat of black-brown slip, which resulted in black-brown incised lines which stood out more after firing (design 10). Secondly, the lid was decorated not only with a Goethe quote but also with manganese-purple sponged decoration (design 03h). The quote read: “Zwischen heut und morgen, liegt eine lange Frist – drum lerne schnell besorgen, da du noch munter bist.” (The hours between today and tomorrow are long. Learn quickly to take care of things while you’re still able.) Design 10 first appeared in the Heimberg/Steffisburg region in the late 1830s and, like the sponged decoration technique, may have subsequently been introduced to Langnau by Martin Labhardt (cf. Heege/Kistler 2017/1, Cat. 164). The butter churn was further decorated with applied acorns as well as oak and acanthus leaves. The upper, incised zone had four motifs. One was an image of two lansquenets, one on foot and the other on horseback, and a depiction of an ibex hunt, which was stylistically very unusual. Between these scenes, above one of the recessed handles, was a depiction of a couple embracing. Was this perhaps the journeyman himself (with a baker’s boy cap on his head and a pipe in his mouth) and his sweetheart who, judging by her headscarf and the state of her dress, clearly worked very hard (perhaps on the farm)?

The depiction above the other handle showed a balding man (a jester?) sitting on some kind of magic carpet and pulling a late medieval-style face. A direct parallel for this depiction can be found in an anonymous Flemish diptych from 1520–1530 in the collection of the University Museum of Liège. Another very similar depiction of a gurner can be found on the medieval choir stalls of the Church of St Peter at Solignac Abbey (Limousin) in France. A more comprehensive search of the literature would surely discover further examples. Did Johann Martin Labhardt perhaps come across one of these depictions on his journeyman’s travels? If the gurner is indeed meant to be sitting on a magic carpet, we must assume that Labhardt read the German translation of One Thousand and One Nights, which first came out in the early 19th century, or at least heard people talking about the stories in it

The meaning of the depictions is not immediately clear, be it individually or collectively. Perhaps the piece was simply an opportunity for the journeyman to show off his skills! The same is obvious when we look at the vine branch and grapes below, and even more so from the depiction on the lower part of the butter churn where we see a family of cattle farmers driving their herd up to the Alpine pastures. The moment when cattle farmers left their rented winter quarters for the summer pastures on higher ground was their favourite time of the whole year. Pigs were typically driven up ahead of the cows. After the pigs came the sheep or goats which were usually guided by children or by farm hands and maid servants. It was quite a while later that the herdsman followed with the cattle drive proper. The most experienced cow would go first; she was often adorned, for instance by tying a one-legged milking stool upside down on her head and decorating it with flowers. She was followed by the other experienced cows wearing large cowbells on wide leather neck straps. After that came the younger animals who also wore bells and were accompanied by the other drovers. The end of the procession consisted of the “Plunderwagen” (a trolley, hay cart or a Bernerwägeli, a Bernese type of small carriage), which had enough space, not just for the household effects including wooden vessels for dairying, but often also for pigs and chickens or even the older members of the family.

Looking at the images, it almost seems like a second butter churn, which was also made in 1853, was intended to act as a sequel to the picture story (MKGH 1910-401). It shows the alp or a Maiensäss, the lowest part of the Alpine pasture, with several buildings. A handsome cow can be seen standing in a meadow with an Alpine hut in the background and a herdsman playing a short alphorn in front of it. The picture would not be complete, of course, without a dog to act as a loyal protector and assistant herder, usually an Entlebucher Mountain Dog or an Appenzell Cattle Dog. The next scene shows a cow being milked and the cream then being worked in a plunge churn to make butter. The butter churn is adorned with manganese-purple sponged decoration made of several sponges cut into different shapes combined with rouletting on the upper part. It also has a garland of grapes and vine leaves similar to the first churn. The second ornamental zone contains twisted recessed handles and two mottos, which are probably still valid today: “Lass einen jeden, wer er ist, so bleibst du auch, wer du bist” (“Take everyone as they come, and you will remain who you are too”) and “Auf Freund nicht bau, nicht jedem trau, auf dich selbst schau, sei nicht zu gnau.” (“Do not rely on your friends, do not trust everyone, look after your own affairs, do not be too strict.”) The date was originally scratched out and smudged, but after restoration can now once again be deciphered as “1853”. The flower garland in the bottom zone has a close parallel in the tureen described above (MAHN AA 2055).

This unusual butter churn was donated by Heinrich Angst, the first director of the Swiss National Museum, to the Hamburg Museum of Art and Design in 1910, having acquired it at a Zurich auction in 1909, where it was described as “Bern, Langnau, museum piece, early XIX cent.”.

A pedestal bowl for cream which was decorated by Johann Martin Labhardt and signed on 1st June 1853 by carving his initials into the bottom of the foot also bears images on the theme of Alpine pasture and livestock farming (BHM 6408). The inside of the bowl is decorated with two goats playfighting and the placename “Langnau” underneath. The circumscription reads: “Ich kleiner Napf, ich armer Narr, ich wurd gemacht am halben Tag den 1. Juni 1853 // Christen Gerber im Stadel war Alpmeister zu Gmünden im Jahr 1853.” (“I, a small bowl, a poor fool, was made by noon on 1st June 1853 // Christen Gerber from “Im Stadel” was the Alpine pasture manager at Gmünden in 1853”). “Im Stadel” is a farm in the Gohlgraben area just south of the Gmünden alp.

Having familiarised oneself with Johann Martin Labhardt’s handwriting and preferred decoration techniques, it is possible to attribute other ceramic vessels to him, and probably to Peter Herrmann’s workshop, which shed light on either Labhardt’s or Herrmann’s personality. The most important of these is a TAS 4-type plate with a drainer dated 1853 and signed with the initials “P H” (in private ownership). Bearing in mind the signature of Johann Martin (see BHM 6408), the “H” could also be a ligature of the letters “JML”. The rim of the vessel has the familiar flower garland, and the back has the usual Langnau splashed decoration of the 04b type. The decoration of the well is a special feature. It shows a bald, rather conservatively dressed old man with his mouth wide open in anticipation of the piece of pork, which he is about to eat using a knife and fork. Next to him are agricultural implements; a plough, a carrying frame for cheese, a watering can for a farmer’s garden and a corn sieve on the left, and a sickle, a scythe, a rake and a pitchfork on the right. Two mottos, one at the top, the other at the bottom, provide social criticism in reference to the scene:

«Lass dir rathen liebes Herz,

Quäle nie ein Thier zum Scherz»

“Be advised, dear heart,

never torture an animal for fun”

and

«Ein ieder kennt den Nähr, den Lehr= und Wehrstand,

Es sind in aller guter Dinge drei,

Doch reimet sich auf alle auch der Zehrstand.

Wann ist es denn mit dem einmal vorbei?»

“Everyone knows the three estates: the nourishing estate, the teaching estate and the warring estate, but another rhymes with all of these, the draining estate. When will this one finally come to an end?”

Most modern readers will probably have difficulty understanding the archaic term “Zehrstand”. In a book entitled “Epigrammatische Spiele” (“Epigrammatic Games”) published by Johann Christoph Friedrich Haug (German poet, 1761–1829) in Zurich in 1807, this estate (of “drainers”) was equated with “advocates”. The “teaching estate” referred to the clergy, the “warring estate” to the military and the nobility, the “nourishing estate” to the farming and merchant class. In a book of 1798 dedicated to Emperor Joseph II, the “Zehrstand” was equated with public officials, while an article written in 1817 associated it with the “wealthy clergy”, and a Bavarian tract printed in 1784 linked the term to clergy and officials, particularly court and administrative officials. The “Allgemeine deutsche Bürgerzeitung” no. 28, dated 5th April 1832, finally, equated it with the minor nobility whose members strove to attain state employment. The plate obviously deals with a term which was not very clearly defined and where it remains unclear whether it refers to the church and its clergy, pastors and congregation of religious, or to the state and its officials. The image in the centre of the plate points to the latter. It can therefore be seen as a comment on a topic that was often discussed: the appropriate level of state administration. While such a sweeping statement was probably not actually justified even at the time, we would now probably see the plate as a form of “state bashing”. Who in Langnau or Bern could have annoyed Johann Martin Labhardt and Peter Herrmann so much in 1853?

Judging by the style of decoration and drawing, three further ceramics can be attributed to Martin Labhardt: two TLR 3c-type plates and one TAS 7-type plate with a drainer (MAHN AA 1170, MKB VI-02218, SNM LM-040724,). All three share an unusual feature: for some unknown reason they bear wrong dates (1777, 1502 and 1620). Even if Labhardt’s Langnau period (1849–1854) was not known, it would be clear to us today from the vessel shapes and decoration techniques that these dates could not have been correct. However, we cannot say if this would also have been clear to any potential buyers at the time they were made, and so it is possible that the dates were intended to give inexperienced buyers – perhaps the first English tourists and souvenir hunters, or perhaps even the first collectors of Langnau wares – the impression that these vessels were a lot older than they actually were.

The plate supposedly from “1777” shows an exciting boar hunt (MKB VI-02218) on the front and the classical Langnau design 06d on the back. The “1502” plate bears the motto: “Mehr wert als Geld und Gut, ist doch ein froher Mut” (“A cheerful spirit is worth more than money or worldly goods”) (SNM LM-040724). The plate from “1620” shows a fair bit of damage but is decorated with a cartouche and the motto “Die Zeit die fällt mir gar zu schwer, Ach wenn mir bald die Mahlzeit wer” (“Time is passing oh so slowly, if only it was dinner time soon”). Below the motto is a cock surrounded by flowering branches (MAHN AA 1170). In 1911, pastor Karl Ludwig Gerster (1848–1923) from Kappelen near Aarberg had actually been fooled into believing that the date on the plate was genuine and identified it as the “oldest Langnau dish” (Gerster 1911, 141).

Herrmann potters’ family tree, Langnau

Translation: Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Früh 2005

Margrit Früh, Steckborner Kachelöfen des 18. Jahrhunderts, Frauenfeld 2005.

Gerster 1911

Ludwig Gerster, Sprüche und Inschriften auf Bauerngeschirr und Glas, in: Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde 15, 1911, 138-147, 204-213.

Heege/Kistler 2017/1

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Poteries décorées de Suisse alémanique, 17e-19e siècles – Collections du Musée Ariana, Genève – Keramik der Deutschschweiz, 17.-19. Jahrhundert – Die Sammlung des Musée Ariana, Genf, Mailand 2017.

Heege/Kistler 2017/2

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Keramik aus Langnau. Zur Geschichte der bedeutendsten Landhafnerei im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 13), Bern 2017, 380-386