Matzendorf pottery in CERAMICA CH

Now available: Jonathan Frey, Erkennungsmerkmale von Matzendorfer Fayencen

Roland Blaettler 2019 (with additions from 2022/23)

Introduction

The Canton of Solothurn had one faience and refined white earthenware manufactory in Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf. It was founded at the end of the 18th century and was in operation until the beginning of the 21st century. There are very few centres of production in Switzerland that were in operation for a similar period of time.

Solothurn’s museum collections reflect the special role the manufactory played in the canton’s history. They not only include what we now consider to be characteristic Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf wares but mirror the entire history of its production, which at times was rather volatile and, throughout the entire 20th century, had to contend with controversial attributions. From the very beginning of the 20th century, collectors and antiquarians began to attribute faience vessels to Matzendorf which we now recognise as products from several other faience manufactories in and around Kilchberg on Lake Zurich. The erroneous attribution of such pieces to Matzendorf was officially supported by the first work on the subject, published in 1927 by Fernand Schwab. Maria Felchlin later went on to claim faience and refined white earthenware pieces from eastern France as originating from Matzendorf. These “annexations” resulted in a broadening of the Matzendorf production range that would have consequences for collectors throughout the canton.

Matzendorf wares and wares that at the time were presumed to be from Matzendorf still make up an important part of the pottery collections of institutions that have a cultural and historical collecting mandate, for instance the Museum Blumenstein in Solothurn (c. 70%), the Olten Historical Museum (c. 25%) and the Local History Museum at Alt-Falkenstein Castle (70%). The collections in Matzendorf itself, i.e. the Maria Felchlin collection and the pottery museum, are dedicated entirely to the Matzendorf issue, with the former representing a true reflection of the theories formulated by Maria Felchlin, probably the most prominent personality in the manufactory’s historiography.

Given the central role played by the Matzendorf question in the developments of the Solothurn collections, it seems fitting to first take a look back at the history of the manufactory and how its actual and alleged products were interpreted by the people who studied the topic, in particular Fernand Schwab, Maria Felchlin and Albert Vogt.

The history of the Matzendorf Manufactory

As stated by the historian Albert Vogt, the company that is commonly known as the Matzendorf Manufactory was, in fact, located within the territory of the neighbouring municipality of Aedermannsdorf (Vogt 2000, 12–13). This long ignored inaccuracy was not amended until 1883 when the old factory was replaced by the newly founded public limited company “Tonwarenfabrik Aedermannsdorf”.

The first account of the manufactory’s history was written in 1927 by Fernand Schwab. Entitled “Die industrielle Entwicklung des Kantons Solothurn” (The industrial evolution of the Canton of Solothurn), the book remains a fundamental reference work for Solothurn’s economic history. The chapter on the Matzendorf Manufactory was the first important archive-based study on the foundation and development of the enterprise (Schwab 1927, 459–477).

Maria Felchlin (1899–1987), who was born in Olten and later practiced as a doctor in the town, made her mark as a women’s rights activist, played a role in the cultural life of her town and became a defender of the image of Matzendorf faience (Bloch 1989). She had literally fallen in love with the pottery from the Dünnerntal valley, had probably begun collecting it as early as the end of the 1920s and decided to continue the work that Fernand Schwab had begun. The preliminary results of her study were published in a well-researched article in the 1942 Jahrbuch für solothurnische Geschichte (Felchlin 1942).

The chapter “Faience and refined white earthenware from Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf” at the first national exhibition organised by the “Freunde der Schweizer Keramik” (Friends of Swiss Pottery) at Jegenstorf Castle in 1948 was curated by the collector Fritz Huber-Renfer. His exhibits and the associated texts in the catalogue faithfully followed the hypotheses put forward by Maria Felchlin. He also concurred with Felchlin’s opinion, which she defended with conviction, that the faience objects in the so-called “Blaue Familie” (Blue Family) style had originated from the workshop of Niklaus Stampfli in Aedermannsdorf. The majority of the 154 objects in the exhibition came from the collections of Huber-Renfer and Felchlin (Jegenstorf 1948, 72–86). The second exhibition of Swiss pottery at Nyon Castle in 1958 included 78 objects from the collections of Felchlin (33 exhibits), Blumenstein, Huber-Renfer and A. Probst from Bad Attisholz, which were attributed to Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf using Felchlin’s system of classification. This shows that Maria Felchlin was the authority in this field. To mark the 1000-year history of Matzendorf in 1968, she published a revised edition of her history of the manufactory where most of the changes and additions related to the chapter on production (Felchlin 1968).

As part of his thesis on the economic, social and cultural history of the municipality of Aedermannsdorf, Albert Vogt carried out extensive archival studies during which he discovered hitherto unknown documents pertaining to the history of the manufactory (Vogt 2003). He first published his findings in an article in the Jahrbuch für solothurnische Geschichte (Vogt 1993). A few years later he was commissioned to edit a history of the Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf Manufactory published by the “Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik” (Friends of Matzendorf Pottery) to mark the 200th anniversary of the ceramic industry in Matzendorf (Vogt et al. 2000). More recently: Matzendorfer Keramik 2022.

The early days of the manufactory

Schwab reminded readers that Solothurn patricians had from as early as the 1760s considered setting up a faience manufactory modelled on the one in Bern. Some of the members of the Economic Association eventually began to search for raw materials within the territory of the canton. Schwab tells the story of how two members of the association, Canon Viktor Schwaller and Ludwig von Roll (1771–1839), discovered a clay deposit near Aedermannsdorf during a legendary ride into the Dünnerntal valley. Schwaller and von Roll purchased the land and were granted permission by the council in Solothurn to build a manufactory producing fire-resistant cookware “because the soil is suitable for the purpose” (Vogt et al. 2000, 20). Construction work commenced in 1797/98. The people of Aedermannsdorf, however, feared that the amount of wood required for the new industry would destroy the forest and that the alien craft would bring foreigners and people of low morals to the valley. They put up fierce resistance and when the resulting conflict was exacerbated even further by the French invasion of 1798, the superintendent of the Helvetic Republic in Balsthal was sent to Aedermannsdorf to mediate between the parties involved. He appears to have been successful, but Schwaller soon left the project and von Roll effectively carried out the construction of the manufactory on his own. This was his first important deed as a pioneer of industry in the Canton of Solothurn.

Maria Felchlin added new information to the picture that Schwab had painted of the manufactory’s early period which she found in the archives of the municipalities involved. Schwab had been surprised when he could only find a single worker from abroad among the company’s employees. This was Josef Beyer, a painter from Dirmstein (now Rhineland-Palatinate), who was first mentioned in 1837, relatively late. Felchlin managed to identify other non-nationals – people from France and Germany – who had clearly been hired as skilled workers between 1801 and 1810 (Felchlin 1942, 11–12). Looking through the 1801 baptismal register of Matzendorf, Felchlin also found the name Margaritha Contre, née Leffel, from Sarreguemines, “Directrix in der Fabriqs.” (directress in the factory). This led her to conclude that the lady must have been the director of the manufactory, which she viewed as proof of von Roll’s progressive attitude (Felchlin 1942, 12; Felchlin 1968, 166). In 1993, Albert Vogt corrected this rather hastily arrived at conclusion by identifying Franz Contre, Margaritha’s husband, as the actual manufactory director.

Vogt was subsequently also able to find out more about the circumstances surrounding the founding of the company and the commencement of the production at the manufactory. Ludwig von Roll’s primary concern was to find competent skilled workers to guarantee the factory’s production in the period following the construction. He contacted Johann Jakob Frei (1745–1817), a faience maker from Lenzburg, who four years previously had presented himself to the council in Solothurn seeking permission to build a porcelain factory in the canton. Frei, who had been in financial difficulties since 1790 (Ducret 1950, 73–87), had at the time been brusquely refused. The offer of a position as technical manager of the new manufactory was therefore most welcome.

When studying the records of the district court in Balsthal, Vogt found out that von Roll had signed a contract with Frei in July 1798, in which the latter was promised 100 Louis d’or in exchange for teaching the company management what they needed to know about the construction of the kilns and mixing of the clay for the production of faience, English refined white earthenware (called pipe clay in the records) and brown and white cookware so that production could proceed without him once everything was up and running. Frei then moved to Aedermannsdorf with his family. According to Frei, he fulfilled his side of the contract, and the manufactory was able to commence production in September 1799. The company, however, declined to pay the first instalment as agreed. The court in Balsthal sided with Frei, but upon appeal before the cantonal court in Solothurn he was forced to complete the remaining kilns and to show Joseph Eggenschwiler, von Roll’s associate, how to produce refined white earthenware within a period of five weeks. Frei, who was not adept at manufacturing refined white earthenware, was unable to fulfil the task and Vogt presumed that Frei had left Aedermannsdorf in late 1799 or early 1800. Eggenschwiler was left to complain to the local tax agent that he was only able to work “on a trial basis” and was now looking for qualified craftsmen but not having much success (Vogt 1993, 424–425).

In 1970, Maria Felchlin made a sensational discovery when she stumbled upon the recipe booklet of the manufactory, which she subsequently published under the title “Das Arkanum der Matzendorfer Keramiken” [The Secret of the Matzendorf Ceramics] (Felchlin 1971). The booklet, which had been handed down through several generations of the Meister family, contained various recipes for making faience, refined white earthenware and brown cookware. The main section dated from 26th July 1804, bore the initials “F. C.” and was countersigned by Joseph Bargetzi, the factory’s secretary. Supplementary annotations had been added until 1810. The document provided some important information about the early period of the company. It showed that the white firing clay required to make refined white earthenware was imported from Tenningen in the Breisgau region, while the faience was produced using clays from Laupersdorf, Matzendorf and Aedermannsdorf. Because the chapter on faience was decidedly less detailed than the section on refined white earthenware, Felchlin rightly concluded that the Matzendorf workers had already been familiar with this technique and that faience had been produced there from the very beginning. The information on brown cookware was similarly brief and that particular chapter was dated 1806, which suggests that this production, too, dated back to the early period.

While studying the records of the municipal archive of Aedermannsdorf, which Felchlin was oddly unaware of, Albert Vogt came across the name of the person who had taken over the running of the manufactory after Frei’s departure: Franz Contre from Sarreguemines in Lorraine. After April 1804, Contre no longer appears in the records, but it is practically certain that he was the author of the recipe booklet signed “F. C.”. He must have written it shortly before he left the company (Vogt 1993, 426). Vogt was also able to add a considerable number of names to Felchlin’s list of workers. For the period of between 1800 and 1808 he listed a dozen skilled workers from France and Germany, who were employed by the manufactory as throwers, painters, kilns men and modellers (Vogt 1993, 429). The first of these in all likelihood came to Aedermannsdorf with Franz Contre. It was thanks to these specialist workers that the company was finally in a position to begin producing refined white earthenware. Several of the workers mentioned by Vogt came from well-known French refined white earthenware factories like Montereau, Niderviller, Lunéville and Sarreguemines.

Urs Meister holds the lease (1812–1827)

Fernand Schwab tells us that Ludwig von Roll then bought the hammer mill from the Dürholz brothers in Aedermannsdorf in 1810 and began to turn his hand to the metal industry. He withdrew from his first manufactory and leased it out to Urs Meister, a local man. Schwab bemoans the lack of written sources that could shed light on the new chapter in the manufactory’s history and goes on to quote a report from the revenue office dated 1825. It finds fault with the faience from Matzendorf which is described as being of an inferior quality than the French wares and it also states that the Matzendorf refined white earthenware is not comparable to similar products from Nyon (Schwab 1927, 464).

The second document discovered by Schwab is an application dating from 1826 to the municipal council for permission to run a faience and refined white earthenware lottery with the aim of shifting some of the stock and repaying creditors. According to the document, the manufactory was being undermined by growing competition from abroad, it had been employing 22 local workers since 1812 and was producing wares with a market value of 16,000 Swiss francs, with seven out of every eight vessels being sold to customers outside of the canton (Schwab 1927, 465). Whatever the result of the lottery, Urs Meister’s finances did not recover sufficiently to allow him to continue running the business. He resigned and was replaced by a board consisting of Niklaus Meister, three of his sons, Ludwig, Melchior and Josef, as well as Johann Schärmeli, Viktor Vogt and Josef Gunziger. The Meisters and Schärmeli lived in Matzendorf, while Vogt and Gunziger lived in Aedermannsdorf.

In 1829, Ludwig von Roll went bankrupt and was forced to sell his properties. The factory in Matzendorf was bought by Urs Meister’s seven successors. Ludwig Meister (c. 1790–1869) was managing director of the company which was now known as “Ludwig Meister und Mithaften” (Ludwig Meister and partners) or “Ludwig Meister & Compagnie”. All partners except Niklaus Meister worked for the company. The shares would remain in the hands of the Meister, Gunziger and Vogt families until 1883 and various intermarriages eventually transformed the company into a family business in the actual sense of the word. When Ludwig Meister died, his son Johann (1825–1876) took over the management and upon Johann’s death, it was taken over by his cousin, Niklaus Meister (1821–1897). In 1883, the “Ludwig Meister & Cie” partnership was made a public limited company.

Vogt obtained the information for this period from a small number of available sources, for example the Solothurn Government’s statement of accounts from 1836/37, which states that “due to a lack of suitable clay, fine faience and refined white earthenware were no longer produced”. It appears that only ordinary faience and cookware were still being made by the manufactory. The statement also mentions that the factory was now employing 19 workers and that the majority of its products were still being sold in the Cantons of Bern and Basel, and to a lesser extent in the Cantons of Lucerne and Aargau (Schwab 1927, 467).

For the period between 1850 and 1883, Albert Vogt found that the company now only employed between nine and twelve workers, which suggests that production had actually decreased. The turnover between 1858 and 1862 was an average of 5,000 francs per year with peaks of around 7,000 francs; this decreased between 1866 and 1870 to lows of around 3,500 francs. If turnover was this low, output must also have decreased. During its entire existence and up until the end, however, the company always sold the majority of its wares in the Bern, Basel and Aargau regions. Vogt states that these fluctuations were consistent with the general economic situation at the time (Vogt et al. 2000, 37–38).

Thonwarenfabrik Aedermannsdorf (Aedermannsdorf Pottery Factory) (1883–1960) and Rössler AG (1960–2004)

In 1883, the public limited company “Thonwarenfabrik Aedermannsdorf” was set up at the site of the Matzendorf Manufactory. Most of its shareholders lived outside the Dünnerntal valley and were part of the political and economic élite of the canton. The new company did well. Thanks to the local clockmaking industry, which was experiencing a boom period, the construction industry was also given a boost, and the newly established department for the manufacture of stoves and tiled stoves at the pottery factory became a highly profitable branch of the business. At the end of 1890, the factory abandoned the use of local raw materials and began importing its clay from the Palatinate region of Germany and from Czechoslovakia. In 1884, it had 13 members of staff, rising to 38 in 1885 and 54 in 1897. The factory was destroyed by fire in 1887 and again in 1913 but on both occasions, it was rebuilt immediately and modernised. In 1913, for instance, production was partially mechanised, and the kilns were converted to coal. At that stage the company had two production lines of equal importance; on the one hand it made stoves and stove tiles, on the other it produced manganese-glazed crockery, as observed by Fernand Schwab during a visit to the factory in 1924.

In 1927, Alfred von der Mühll, an entrepreneur from Basel, purchased the public limited company “Thonwarenfabrik Aedermannsdorf” (Aedermannsdorf Pottery Factory), which was in financial trouble at the time. The company had been forced to reduce its workforce since 1926. While initially the situation improved under the new ownership, the world economic crisis began to have an impact on the company too. In 1934, an art department was established under the leadership of the Bern ceramicist Benno Geiger. When crockery imports from neighbouring countries ceased during the Second World War, the factory experienced an upswing, and new lines of production were added to the traditional brown manganese-glaze ware.

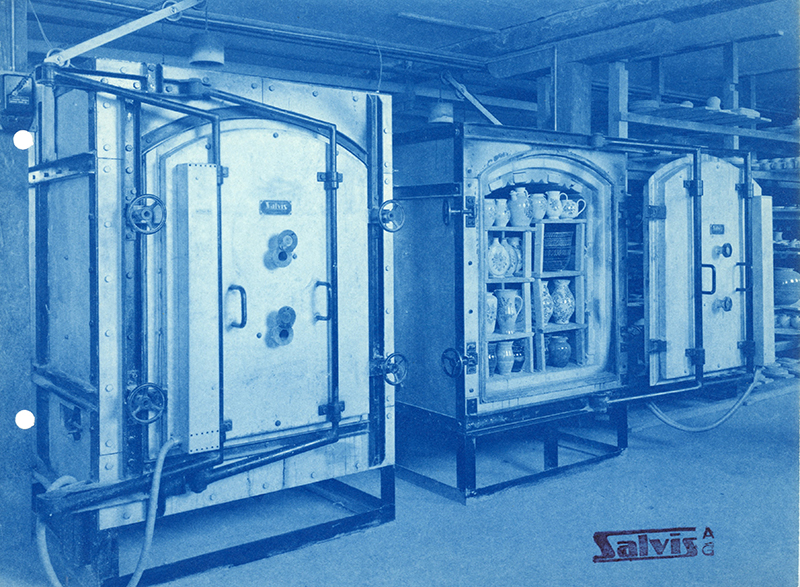

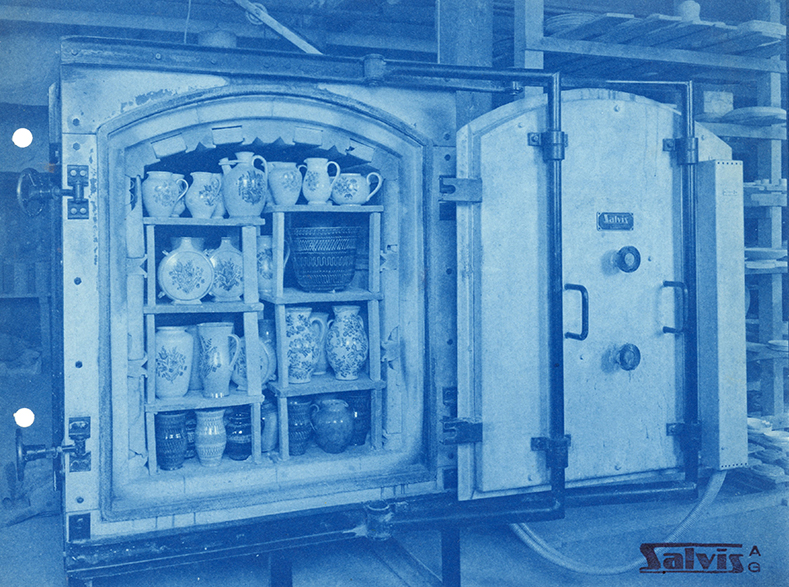

The kilns in Aedermannsorf as shown in a Salvis A.G. brochure printed in c. 1943.

After 1947, the factory had to once again compete with an increasing number of rival companies from abroad. In 1960, it was sold to the industrialist Emil Rössler from Ersigen in the Emmental valley. The new public limited company, Rössler AG, now specialised in producing refined white earthenware and, from 1963 onwards, porcelain. Production in Aedermannsdorf ceased in 2004.

Two other potteries in Matzendorf/Aedermannsdorf

The Studer workshop in Matzendorf (1826-1854)

The Handbuch über den Kanton Solothurn (Handbook of the Canton of Solothurn), published in 1836, mentions “two faience factories in Matzendorf” without giving any further information (Strohmeier 1836, 101 and 232). Fernand Schwab did, in fact, identify a workshop which was owned by a man called Urs Studer (1787–1846), who is mentioned in the register of deaths as a “faience manufacturer”. Studer had bought a house in Matzendorf in 1817, and an entry in the 1825 land register confirms that he had set up a potter’s workshop there. Schwab visited the site in the 1920s, at which stage the workshop was still clearly recognisable, but he saw that it had been quite small and could only have accommodated three workers at most (Schwab 1927, 474).

Albert Vogt later added that the 1808 census listed Studer as a manufactory worker (Vogt 1993, 430) and that in 1826 he sought permission to install a potter’s kiln in his house (Vogt et al. 2000, 63). In 1846, Studer’s sons, Urs junior and Josef, took over the workshop and continued to run it until 1854. We do not know what the workshop produced. By contrast to Albert Vogt, we do not believe that it produced faience, but rather glazed or slipped earthenware.

The Stampfli workshop in Aedermannsdorf and subsequent owners (1803-after 1907)

In the first edition of her monograph, Maria Felchlin recounts a meeting with a local person who told her that a great-grandfather of theirs, a man named Stampfli, had produced faience wares of the “Blue Family” type (e.g. MBS 1912.107; MBS 1912.126). This encounter prompted Felchlin to look for more information and she did, in fact, uncover a Niklaus Stampfli (1811–1883), who was a potter in Aedermannsdorf from the 1840s until 1879/80 before moving to Bellach to live with his daughter. Stampfli was known locally by his nickname “Hafnerchlaus” (Chlaus the potter) and his workshop was known as “Hafnerhütte” (the potter’s hut) (Felchlin 1942, 38–42).

It was Albert Vogt, who again added the information that a man called Urs Josef Stampfli (1775–1847) had been granted permission in 1803 to install a kiln on common land in Aedermannsdorf, where it appears he mainly produced stove tiles. His son Niklaus also trained as a potter. In 1833, he was still living in Aedermannsdorf, but later moved to Crémines in the Bernese Jura region, where he lived for the next ten years. The Matzendorf Pottery Museum has two plaster moulds he used for making plates, one of which bears the incised signature “Stampflÿ 1834”, the other has the initials “N. S.”. This valuable evidence suggests that Stampfli knew how to make plaster moulds (Vogt et al. 2000, Fig. 13). He returned to Aedermannsdorf between 1842 and 1845, where he may have worked as a day labourer for the manufactory. When Urs Josef died in 1847, Niklaus took over the workshop. In the same year, he participated in a trade exhibition in Solothurn, putting on display “a small earthenware bottle with a black glaze” (Kat. Solothurn 1847). In 1851, Niklaus Stampfli was forced to sell the workshop, and four years later he was declared bankrupt, even though he may have continued to work as a potter until 1858 (Vogt et al. 2000, 61). Vogt assumed that he subsequently worked at the manufactory until he left Aedermannsdorf in 1879/80, as he is known to have lived in a house owned by Josef Vogt, one of the factory owners in 1860 and in the manufactory building itself in 1870. Given his low weekly wages of 5 francs, Vogt assumed that he worked in the manufactory building producing ceramics not only for the company but also for himself (Vogt et al. 2000, 56).

As far as the “potter’s hut” founded by Urs Josef Stampfli is concerned, it continued to remain in operation under various owners until the early 20th century, starting with the potters Josef Wiss (from 1858 to 1862) and Johann Schuppisser (from 1862 to 1865); in 1865, the workshop was bought by Urs Josef Bläsi, who rented it out to two potters, Peter Siegenthaler from Langnau and Johann Schneider from Niederhünigen. In the late 1880s, it was taken over by Bläsi’s son Rupert (1868–1911), who had worked for the pottery factory for a few months in 1885 (Vogt et al. 2000, 61–62). According to an advertisement published in November 1907, Rupert Bläsi sold “all types of milk bowls and milk jugs as well as flowerpots and flowerpot dishes”.

The identification of Matzendorf products: the Matzendorf/Kilchberg-Schooren controversy

Fernand Schwab

In his pioneering work of 1927, Fernand Schwab not only related the history of the Matzendorf faience manufactory; he also used the collections of the Solothurn Museum (later the Museum Blumenstein) in an attempt to find out what the manufactory had produced. Products with names from the region, which could have been associated with Matzendorf were rather rare and mostly dated from the later period of production from the mid-1840s until around 1880 (Schwab 1927, Fig. 2 following p. 468).

Schwab found the first mention of faience production in the 1825 report from the revenue office. Because he was not aware of any corresponding products from the period of von Roll’s reign, he presumed that the manufactory had only produced refined white earthenware in the early years and had not begun making faience until Urs Meister (1812–1827) took on the lease. The same record stated that of the entire output, which was valued at 16,000 francs at the time, seven out of every eight vessels were being sold outside of the canton. But what did these Solothurn exports look like?

This was where Schwab turned his attention to a relatively large group of faience vessels in the collection of the Historical Museum in Bern, which were traditionally attributed to Matzendorf by both collectors and antiquarians (Schwab 1927, third figure following p. 468). We now recognise most of these objects as products from various manufactories that were in operation in and around Kilchberg-Schooren on Lake Zurich during the period between 1820 and 1850; these had not yet been researched in detail at the time Schwab was writing his book. He thus claimed that the objects in question originated from Matzendorf, as they seemed to be filling a significant gap in the sequence of production in Solothurn before the later, rather mediocre products. The attribution, however, was met with scepticism even back then, with critics noticing that, oddly, this type of faience was almost completely absent from the collections in Solothurn itself. Schwab rejected this line of reasoning, pointing to the importance of the Matzendorf Manufactory’s export business (Schwab 1927, 466) and its annual turnover, which seemed to him to be large enough to warrant his assumption that there had been a type of higher-quality faience which had been produced specifically for the export market. Because he had found most of the examples of this group in Bern, the manufactory’s main sales region, he called this style of painting the “Bernese Design”.

The “Bernese Design”

The “Blue Family”

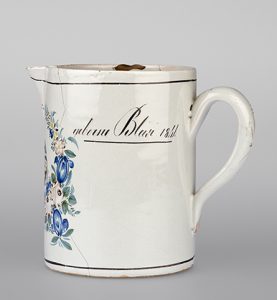

When Schwab set out to date the “Bernese Design”, he pointed to two plates in private collections, which were dated 1822 and which he believed were from the early period of faience production in Matzendorf. In view of the differences between the “Bernese Design” of the 1820s (see, for instance, MBS 2010.2; KMM 68; KMM 69; SFM 138; KMM 71; KMM 96; MBS 1942.20; KMM 91; SFM 84; HMO 8163) and the designs found on the refined white earthenware from the same period in Solothurn, it is indeed difficult to see how Schwab could have come to the conclusion that he did (for instance KMM 67; MBS 1917.36; HMO 8535). Quoting the 1836/37 statement of accounts, which mentions that “fine faience” was no longer being produced and the manufactory was now only making “all kinds of ordinary faience vessels as well as brown cookware”, Schwab dated the end of the “Bernese Design” to c. 1843. He did recognise the significant differences between the “Bernese Design” vessels and the less refined products from the period between 1860 and 1880 but pointed to transitional examples with elements of both the early and the later styles. For the later pieces he coined the term “Blue Family” as blue was the predominant colour in these, particularly with regard to the outlines (e.g. MBS 1912.128; KMM 507).

The “Blue Family” was clearly of a lower quality compared to the “export wares” and Schwab’s “Bernese Design”, in terms of both the shapes and the painting. He believed that a difference as obvious as this had to be an indication of a decline. He therefore viewed the “Blue Family” as an “occasional production line” purely intended as giveaways for a limited group of customers in the Dünnerntal valley and made by workers from the manufactory but outside of normal working hours or even in their own homes. They had nothing to do, he believed, with the production of the manufactory itself. This theory of an “amateur production” was later further developed by Maria Felchlin. In summary, Schwab believed that the Matzendorf Manufactory began to produce wares with the “Bernese Design” from the early 1820s specifically for customers in the neighbouring Cantons of Bern and Basel and that production ceased in c. 1837 for economic reasons. Sometime later, a few of the manufactory’s workers began to produce “Blue Family”-type wares for a small number of local customers. This was an unofficial range of lower-quality products which were not professionally made, a rather pale reflection of what had once been created at the manufactory. In terms of its export business, he believed that at that stage the manufactory was concentrating on producing “brown cookware” (Schwab 1927, 473).

Maria Felchlin

Then Maria Felchlin took up the baton. In her own energetic way, she began to expand what was known about the pottery from Matzendorf starting out from the foundations that Schwab had laid. She also made an in-depth study of the manufactory’s production by delving deeper into and adding further detail to Schwab’s theories. She used the categories “Bernese Design”, “Blue Family” and “brown cookware” as defined by Schwab and then added her own information, taking a more systematic approach and developing her own theory, the so-called “service hypothesis” (Felchlin 1942, 22–25). The brochure written by Urs Meister for his lottery in 1826 mentioned a dinner service for 24 people and Felchlin wanted to find out what exactly this could have comprised of.

The “Crane Design” – While trying to answer this question, she came across a group of faience pieces owned by a lady living in Trimbach near Olten. They were decorated with the famous camaieu purple “Crane Design”, which was said to have come from the “St. Urs und Viktor” inn in Boningen and was thought to have been made by the Matzendorf Manufactory (Felchlin 1942, Pl. VIII, Fig. 13). She later succeeded in buying the pieces for her own collection (SFM 34; SFM 38; SFM 39).

In Maria Felchlin’s opinion, these vessels had to be representative of the first phase of faience production in Matzendorf, i.e. they had to pre-date the “Bernese Design”, and she therefore dated them to between 1808 and 1820. In a way, this opinion seemed to have been officially confirmed by an exhibition that was staged in Jegenstorf in 1948 (Jegenstorf 1948, 72–73). Seeing a faience plate bearing the date 1801 which had been discovered in the collection of the Solothurn Museum (MBS 1912.220), Felchlin changed the date of the beginning of the faience production and was now of the opinion that the factory had produced both refined white earthenware and faience from its very beginning.

The “Bernese Design” – Much of her energy, however, went into the “Bernese Design” hypothesis, which was increasingly being questioned by the Zurich experts but which she set out to defend, no matter what the obstacles. The first objection was made by Karl Frei, the director of the Swiss National Museum, who died in 1953. He had published the first seminal work about the faience production at Kilchberg-Schooren in 1928 (Frei 1928), shortly after Schwab’s 1927 work had come out. When Felchlin visited the National Museum in 1932, she was shocked to see that they had only attached the Matzendorf label to faience objects from the “Blue Family”, while the “Bernese Design” was attributed to Kilchberg (Felchlin 1968, 154). She objected to this and put forward a whole series of arguments which, she believed, made a case for Solothurn, but which later turned out to lack credibility (Felchlin 1942, 30–38).

Refined white earthenware

Pointing to a tureen owned by the family of the Balsthal town clerk Bernhard Munzinger (SFM 1), Felchlin further laid claim to a group of refined white earthenware vessels with fine floral relief decoration, and also attributed them to Matzendorf (SFM 1; SFM 2; SFM 3; SFM 4; SFM 9; SFM 10; SFM 15; SFM 18; SFM 23; SFM 24; SFM 25; SFM 26).

She presented this new addition to the production range at an exhibition in Nyon in 1958, thus also putting it up for public discussion (Nyon 1958, 38; Felchlin 1968, 176–178).

“Amateur production” – “Aedermannsdorfer”

Objects that seemed to Felchlin not to meet the standards expected of the Matzendorf Manufactory’s official production range, were labelled by her as “amateur products” or leisure time projects. As far as Schwab’s “Blue Family” was concerned, however, she developed a new theory. A great-grandson of the potter Niklaus Stampfli had told her that his ancestor had made precisely the types of vessels that she felt could not have been produced by the manufactory. Based on this information, she now attributed them to the Stampfli workshop, the “potter’s hut” in Aedermannsdorf and called them “Aedermannsdorfer” (Aedermannsdorf wares). Other descendants of Niklaus Stampfli had purportedly confirmed to her, that he had produced “not only all kinds of brown vessels, but also white glazed and colourfully painted floral whiteware” (Felchlin 1942, 39) and one of his granddaughters still had an ink stand that Stampfli was said to have gifted to her father, the gendarme Josef Jäggi (SFM 212).

In a sense, the “Blue Family” thus represented the final phase of the “amateur production” and was viewed by Felchlin largely as the products made by Stampfli. She did, of course, see that the designs on the “Blue Family” vessels could not have been created by the same person, but since they were now no longer considered part of the official production range of the manufactory, she simply stated that they were “of hardly any consequence for ceramic research or historical interest” (Felchlin 1942, 62). A rather flippant way of dismissing the problem!

Matzendorf wares in the Strasbourg style

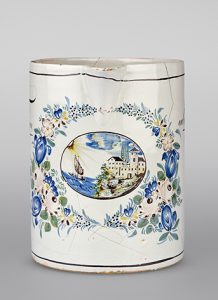

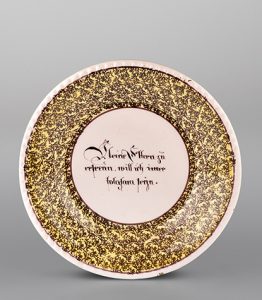

In 1953, Maria Felchlin discovered a tureen in the collection of the Olten Museum, which had overglaze painted decoration in the eastern French style and a dedication to “Elisabetha Winter” (HMO 8692). A few years later she came across another example in the Blumenstein Museum in Solothurn with the same style of decoration and a dedication to “Anna Maria Mohlet and Hans Georg Hugi Zuchwil” (MBS 1920.83).

Searching the archives she found records for these Solothurn people and was able to date the tureens to between 1812 and 1815. Felchlin was now tempted to connect these faience objects with Matzendorf and to view them as objects made by the potter Urs Studer who worked at the manufactory. She first presented her hypothesis at the annual assembly of the Historical Association of Matzendorf in 1957 (Felchlin 1957) and again at the exhibition in Nyon Castle in 1958, where she also showed another series of faience objects; based on comparisons with the tureens mentioned, she now identified these as “Matzendorf wares in the Strasbourg style” (Nyon 1958, 37–38; Felchlin 1968, 196–210; see AF 22-033-00; AF 22-034-00; MBS 1920.83; HMO 8064; HMO 8065; HMO 8066; HMO 8107; HMO 8108; HMO 8113; HMO 8114; MO 8118; HMO 8119; HMO 8120; HMO 8126; HMO 8128; HMO 8129;HMO 8723; HMO 8680; HMO 8692; HMO 8713; SFM 43; SFM 46; SFM 48; SFM 50; SFM 51; SFM 52; SFM 53; SFM 54; SFM 55; SFM 56; SFM 58; SFM 60; SFM 61; SFM 62; SFM 63; SFM 64; SFM 66; SFM 67; SFM 68; SFM 69; SFM 71; SFM 72; SFM 205; SFM 206).

The following can be added about the tureens shown above: While the two objects appear to be rather exotic to French ceramic experts today, because of both their shape and their painting, it is still quite possible that the dedications, which were added in black overglaze paint and which clearly referred to people from Solothurn, were made on commission by a factory outside of Switzerland. The inscription on the tureen MBS 1920.83 cuts into the decoration and was thus clearly added by a different person. The handwriting on HMO 8692 is unsteady and unassured as if the person was not very familiar with the German cursive script. Both tureens undoubtedly originated from a highly productive manufactory, many of which existed at the time in the towns and villages of eastern France, and not from a small workshop like Studer’s in Matzendorf. Given how important the Swiss market was for the manufactories of eastern France, it is indeed possible that they produced vessel shapes to suit the specific tastes of their Swiss clientele (pers. comm. Jacques Bastian). In any case, we are not aware of a manufactory on Swiss soil that would have been capable of producing ceramics with overglaze decorations of this quality at that time.

Rudolf Schnyder

In 1997, Hans Brunner, the director of the Historical Museum in Olten, staged an exhibition entitled “200 Jahre Matzendorfer Keramik” (200 years of Matzendorf pottery making) with the intention of critically examining the theories put forward by Schwab and Felchlin. He commissioned Rudolf Schnyder, the former curator and head of the department of ceramics at the Swiss National Museum, to develop a concept and curate the exhibition. Schnyder took the opportunity to give a detailed presentation of his view on the Matzendorf production, which he had already outlined in the catalogue accompanying the 1990 exhibition “Schweizer Biedermeier-Fayencen, Schooren und Matzendorf” (Swiss Biedermeier faience objects, Schooren and Matzendorf) (Schnyder 1990). He used formal, technical and stylistic criteria to show that the products from the Matzendorf Manufactory had their own specific style and differed quite substantially from the objects produced by the factory on Lake Zurich. In an effort to visualise the character and profile of the Matzendorf production, he made sure that the exhibition would only include objects made in Matzendorf. This meant that even the so-called “Bernese Design” was only represented by examples from Matzendorf and not from Kilchberg. He also refrained from illustrating the bold hypothesis regarding the Matzendorf production of faience objects decorated with crane motifs, of refined white earthenware with fine floral decoration in relief and of “Matzendorf wares in the Strasbourg style”. The “Blue Family”, by contrast, was once again presented as a late phase in the evolution of the manufactory’s official production rather than as outliers created by amateurs dabbling in faience production in their spare time. Moreover, it had been possible, during a review of the most important Swiss collections, to identify hitherto unknown faience objects from the early period of von Roll’s manufactory, which were also presented at the exhibition. The list of exhibits and the revised exhibition texts were subsequently published in: Mitteilungsblatt der Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz no. 121, 2008 (Schnyder 2008).

Albert Vogt

Thanks to his methodologically sound research into the history of the Matzendorf Manufactory, Albert Vogt was able to add a substantial amount of information to the picture of the company history that Schwab had painted and Felchlin had largely adopted. He presented his research results in a book published by the “Friends of Matzendorf Pottery” in 2000 along with the results of archaeometric analyses carried out by Marino Maggetti and Giulio Galetti from the University of Fribourg on behalf of the “Friends”. The hope was that science would finally be able to lay the Matzendorf/Kilchberg controversy to rest (Vogt 2000).

Vogt’s paper answered a series of questions both about the production and about Felchlin’s theories. In his opinion, the hypothesis regarding the crane design, for instance, was not tenable, particularly in view of the results of the archaeometric analyses (Vogt et al. 2000, Mz 43 – SFM 36). The faience objects in question were clearly made earlier, were of French origin, and in all likelihood came from the Franche-Comté region (SFM 34; SFM 35; SFM 36; SFM 37; SFM 38; SFM 39; HMO 8712).

With regard to the subject of “Matzendorf ware in the Strasbourg style”, Vogt presented new dates for Urs Studer’s biography and showed that he had not installed his kiln until 1826. Since the tureens that Felchlin attributed to Studer (HMO 8692; MBS 1920.83) dated from considerably earlier based on their Solothurn dedications, they could not have been made by him, and the ceramic analyses also showed that they originated from abroad (Vogt et al. 2000, Mz 70 – HMO 8692). From our own point of view, we would like to add that ceramic experts unanimously view faience of this type as originating from eastern France, and more precisely, from the Lorraine region. Even though the tureens are quite mediocre in quality, they nevertheless would have required the routine of a relatively large enterprise. This does not fit with Studer’s workshop which, according to Schwab, was quite small. Moreover, these manufactories would have been proficient in polychrome overglaze painting, which was a technique that Studer would not have had the opportunity to learn during his apprenticeship at the Matzendorf Manufactory. Furthermore, an advertisement published in the Solothurner Wochenblatt newspaper in 1806 promoted faience objects made in France and it almost goes without saying that it must have been possible to place an order there for a vessel with a name inscribed (Vogt 2000, 50).

Maria Felchlin was not aware either of Stampfli’s biography, which Albert Vogt researched in more detail. She did not know that he had worked at the manufactory before he became self-employed, nor did she know that he went back to work there after he was declared bankrupt in 1858. Vogt assumed that part of the “Blue Family”, Felchlin’s “Aedermannsdorfer”, was made by Stampfli in the manufactory but at his own expense and after the company had ceased production of high-quality faience in 1845. In this way, Vogt abandoned the idea of Felchlin’s “Aedermannsdorf ware” and circled back to Schwab’s “Blue Family”. Basing his theory on the fact that the “Blue Family” products could not all have been decorated by the same painter, he assumed that several of the factory’s workers had decorated faience vessels for Stampfli outside of normal working hours and without being qualified painters (Vogt et al. 2000, 54). In this regard he followed Felchlin’s notion of an “amateur production”, but in fact placed it within the manufactory.

As for the “Bernese Design”, Vogt agreed with Felchlin. Like her, he pointed to products that were clearly produced in Matzendorf, for instance two shaving basins made in 1844 (HMO 8682; HMO 8896).

He added another made for Johann Bieli (MBS 1912.99) and the service that was produced for Jakob Fluri and Barbara Bläsi (HMO 8156; HMO 8139; HMO 8891; HMO 8897; HMO 8893; HMO 8171; HMO 8175; HMO 8894).

In summary, Vogt concluded that the manufactory’s official production range after 1845 included little more than white undecorated faience and brown cookware. The catalogue of the 1847 trade exhibition in Solothurn appears to bear this out, as the manufactory exhibited 40 pieces of whiteware and 56 examples of brown cookware (Kat. Solothurn 1847). In this context, Vogt quoted the autobiographical account of Peter Binz, a door-to-door crockery salesman whose mother had hawked crockery in the 1850s: “… which was made at the factory in Aedermannsdorf as well as better-quality faience from Horgen, Canton of Zurich, which was delivered to our house … by horse-drawn cart” (Vogt 1995, 15). This must have been faience from Kilchberg and its environs. Vogt believed that the workers had tried to take advantage of the new situation by attempting to imitate vessels from the heyday of the Matzendorf Manufactory, thus creating the “Blue Family” group of objects.

Today’s standpoint, Roland Blaettler

As Felchlin and Vogt showed, the Matzendorf Manufactory produced faience from the very beginning of its existence, while the company did not succeed in making refined white earthenware until Franz Contre arrived after 1800 (marked Matzendorf refined white earthenware, scientifically analysed by Maggetti 2017).

Rudolf Schnyder assumed that the production of refined white earthenware had ceased in 1827 at the latest after Urs Meister left the company and that the new leaseholders and future co-owners had reorganised the business to make it more streamlined.

As regards the “Bernese Design”, we can say that the Matzendorf examples cited by Felchlin and Vogt clearly differ from the designs that Rudolf Schnyder attributed to the Zurich manufactories, with which we would concur. Marked differences can also be seen in the shapes. The shaving basins mentioned above have the irregular lobed design that often occurred and was characteristic of Matzendorf products up to the later phase of the “Blue Family” (e.g. HMO 8887). The same can be said for ink stands, one of which, made for Jakob Büchler (HMO 8223), was clearly painted by the same person as the “Bieli” (MBS 1912.99), “Schärmeli” (HMO 8896) and “Studer” (HMO 8682) shaving basins.

This shape was used in Matzendorf from around 1800 until the end of the 1860s and was decorated with “Blue Family” designs. It clearly differed from the ink stands made in Zurich, whose trays had fronts that were either flat or came to a point in the middle. The Matzendorf pieces had three square feet, while those from Zurich usually had four round ones.

Nor did the type of tureen with palmette-shaped handles (e.g. MBS 1913.73) which was used in Matzendorf from 1830 to 1860 have a counterpart in Kilchberg-Schooren or Rüschlikon.

The Matzendorf objects mentioned were all decorated by the same person. They form a group which, as part of its floral design, included motifs that had already been in use before 1830 and continued to be used after 1860, but cannot be found in any of the designs from Zurich. One such motif was the double rose; used in Matzendorf from 1835 onwards (e.g. MBS 1912.228), it became one of the guiding themes of the “Blue Family” after 1845 (MBS 1912.249; MBS 1912.127). The shaving bowl for Jakob Studer is the only example where a painter, probably Matzendorf’s best painter, used the colour red, or nearly pink, probably by adding ferric oxide (HMO 8682). While iron-red was part of the normal Zurich colour palette, this example from Matzendorf remained an isolated case.

Vogt also added the objects made between 1842 and 1844 for Jakob Fluri and his wife Barbara to the “Bernese Design” group of Matzendorf pieces. Executed by a different person, the painting is not as neat but is similar in style. The motifs on some of these pieces have blue outlines, thus anticipating the “Blue Family” style (e.g. HMO 8156; HMO 8139; HMO 8891).

Thanks to its landscape design, which was rarely used in Matzendorf, a milk jug made in 1844 for Barbara Fluri (HMO 8894) is one of the best pieces produced by the manufactory. Its form, however, with its D-shaped handle is a little unrefined. The Zurich pieces of this type generally have finely moulded strap handles. There is no reason why a Zurich manufactory would have applied a design of this quality to a second-rate shape.

In terms of the quality of the faience produced in Matzendorf, the 1840s were a good period. Before then, the painting style was of a lower standard and was often inspired by motifs that can also be found on products from Zurich (MBS 1912.227; KMM 199; KMM 100; SFM 118); after the 1840s, the quality declined once again, and the “Blue Family” style was eventually developed. In our opinion the transition from one style to the other was entirely natural and a result of an organic process. We do not feel that the theory of a separation between the “Blue Family” and the “official” factory production is tenable. It was a somewhat simplistic way for Schwab and Felchlin to explain the qualitative discrepancy between the local products and the “Bernese Design” group of vessels from the Zurich region, which they were intent on attributing to Matzendorf.

According to information provided to Felchlin by members of Stampfli’s family, he was said to have been involved in one way or another in producing the “Blue Family” range as a manufactory employee. But was he in fact a painter? The moulds from Crémines with his signature, in fact, suggest that he was a moulder. And did he really set up his own production within the manufactory after the company had ceased making painted wares, as suggested by Vogt? It would mean that the firm handed over a fairly substantial part of its local trade to a member of staff. If this were true, then Stampfli would have had to employ several painters to decorate the raw glazed wares produced by the factory, as the pieces were in-glaze painted and this only required a second firing, not a third (Vogt et al. 2000, 53). If, on the other hand, Stampfli produced the faience objects himself, it would have required its own infrastructure within the manufactory, which would hardly have been worthwhile just for the “Blue Family” group of products. Vogt believed that some of Stampfli’s products were “amateur works”. We can, indeed, observe a constant decline in the quality of the painted faience during this late period. We cannot, however, ignore the fact that the designs on this group of vessels followed a clear line, consistently and strictly, attesting to closely monitored work processes and guaranteeing stylistic unity. Generally speaking, the production of faience was technically quite complex and required an organised system of working that necessitated a division of labour. This could not have been achieved by a small, improvised workshop with two or three workers. All the theories put forward by the Solothurn side of the argument involving “a production by amateurs” or “casual work” therefore seem inconceivable in our opinion.

To recap, Vogt believed that after 1845, the manufactory had only produced unpainted faience wares and had no longer employed any professional painters. He further believed that Stampfli had taken advantage of the situation by setting up his own business. If this were true, we would have to ask why Josef Meister (1815–1866) was listed as a “faience painter” in the 1850 census and Franz Nussbaumer (1831–1883) as a “painter in the factory” in the 1860 census (Vogt et al. 2000, 57–58). In other words: why would they have been listed in official records with their casual jobs and not their real professions?

It is clear that various white faience objects were indeed produced by the Matzendorf Manufactory (AF 2-041-00; HMO 8900; AF 22-045-00; AF 22-046-00; AF 22-047-00; MBS 1920.106a; SFM 14; SFM 13).

Even if we accept the notion that Stampfli was given the opportunity to run his own painting shop within the factory which, according to Vogt, would not have been in competition for the factory’s business, it is still highly unlikely that the manufactory would also have allowed him to produce faience vessels given that this was, after all, its main source of income. The shapes of the white objects, the teapots and the shaving basin are completely identical to those in the “Blue Family”, but quite different from the white faience objects made in the Zurich region (KMM 26; SFM 99; KMM 29). This also matches the comments made in the Solothurner Volksblatt newspaper on 22nd May 1847 about the Matzendorf faience objects that were exhibited at the 1847 trade exhibition in Solothurn: “The material is very good, but the shapes could be a little slimmer. A more elegant appearance would surely be beneficial to sales” (Vogt et al. 2000, 52). If the white faience vessels that we would like to attribute to Zurich had really been made in Matzendorf, there is no reason why the manufactory would not have continued to use the same shapes after 1845.

As far as “whiteware” is concerned, we should also bear in mind that this type of pottery played an important role in the production of many manufactories, but is often forgotten because a lot fewer examples of this modest ware have survived than of its painted counterparts (see, for instance, the city waste at Brunngasshalde lane in Bern, which accumulated between 1787 and 1832: Heege 2010, 66–67). We are convinced that this was also true for Matzendorf, and not just for the period after 1845 but for the entirety of its production. Maria Felchlin suspected as much, when she wrote about the “Bernese Design” period: “It [whiteware] was a contingent, and perhaps even the main contingent, of the typical export items” (Felchlin 1942, 58). It must be borne in mind, however, that “whiteware” as a category could have actually included painted faience, which could be ordered directly from the factory.

Since Schwab and Felchlin put so much energy into annexing the Zurich products that bore the “Bernese Design”, they were clearly impressed by the manufactory’s annual turnover figures provided by Urs Meister in 1826. In their opinion, the figures had to represent a substantial production of decorated ware. However, even if we only take part of the Zurich production into consideration, with its array of designs painted by many different people, it would never have been possible for the twenty staff that were said to have worked for the Solothurn manufactory between 1825 and 1835 to produce all those vessels (Vogt et al. 2000, 35–36). We believe that the vast majority of products and exports from Matzendorf were undecorated white faience and brown cookware, both in 1826 and in 1845. Painted faience was always just a minor line of production but it never ceased to be produced. We can assume that from the 1840s onwards, painted wares were almost exclusively made to order, which is borne out by the many dedicatory inscriptions from that time. The “Blue Family”, however, was only the final phase of this development.

Getting back to the archaeometric analyses carried out by Maggetti and Galetti, we can say, firstly, that they took 70 samples taken from objects or fragments made of faience or refined white earthenware, 22 of which came from pieces that we would definitely view as originating from Kilchberg. The physicochemical analysis of 19 of these samples yielded a profile typical of faience from Kilchberg, while the other three were clearly identified as Solothurn products, which obviously raised some questions (MBS 1937.3; KMM 83; SFM 92).

In CERAMICA CH, the analysed objects are listed with their sample numbers (e.g. “Mz 43”) under the heading “Biblio”.

This brings to mind a letter dated 10th November 1851 from the Kilchberg faience manufacturer Johannes Scheller to the municipal council of Balsthal, which was discovered by René Simmermacher and published by Peter Ducret in the Mitteilungsblatt der Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, no. 120, 2007 (Ducret 2007, 10). In it, Scheller seeks permission to use a sheep pen that was no longer needed by the municipality to “store a few loads of clay over the winter months”. This can only mean that the Zurich manufacturer was temporarily using the same clay from deposits in the Dünnerntal valley as the Matzendorf Manufactory was. Though the letter dates from a little later than the “Bernese Design” period, there is nothing to say that clay from the Dünnerntal valley could not have been used in Kilchberg during earlier periods as well.

Whatever the case may be, scientific analysis has reached its limits here. We know that in eastern France, for instance, manufactories quite often sold unpainted white faience to their rivals to help them to fulfil a large order. The fact that the same applied to the clay itself can be seen in Matzendorf, where white-firing clay was imported from Heimbach in the Breisgau region for the production of refined white earthenware (Felchlin 1971, 16–18). While scientific analyses can undoubtedly be of great help and their further development must absolutely be supported, a well-founded knowledge of the historical background of any given subject is nevertheless essential when it comes to reliably interpreting the results.

Refined white earthenware from Matzendorf

Towards the end of the 18th century, English refined white earthenware began to be sold throughout continental Europe. The product was not just reasonably priced but also appealed to contemporaneous tastes and became a symbol of Industrialisation in pottery making. It is therefore no surprise that one of the first projects of entrepreneur Ludwig von Roll was to set up a refined white earthenware factory in Matzendorf. Of course, the production of refined white earthenware in Matzendorf was not without its difficulties. Johann Jakob Frei, the first expert to be tasked with setting up the enterprise turned out not to have the expertise to produce crockery of the desired standard. It was not until Franz Contre arrived from Sarreguemines that von Roll’s dream finally became a reality. Contre is mentioned in Matzendorf’s records from August 1800 onwards. He recruited other experts from the centres of French refined white earthenware production including Niderviller, Lunéville and Montereau. While Contre probably left Matzendorf again in 1804, the production was up and running at that point. From 1800 to 1804, the manufactory employed eleven non-national workers; by 1808 all registered staff members were Swiss nationals. The last dated refined white earthenware vessel bears the year 1821. When Urs Meister who had the lease at that stage, held a lottery in 1826 in the hope of improving the company’s finances, refined white earthenware was still among the range of products available; however, as early as 1824, customs inspector Zellweger had noted that it could not be compared to the competition from Nyon. The Solothurn Government’s statement of accounts in 1836/37 simply states: “Fine wares and pipe clay (refined white earthenware) etc. are not being produced due to a lack of clay.” Unlike faience, the production of refined white earthenware required clays that had to be imported, which of course would have put a lot of pressure on a company that was struggling financially. Therefore, the production of refined white earthenware probably ceased after von Roll’s bankruptcy and the fresh start by a board of leaseholders in 1829. Marino Maggetti was the first scientist to analyse refined white earthenware from Matzendorf (Maggetti 2017).

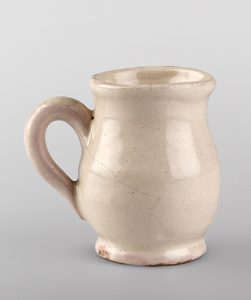

Undecorated Matzendorf ware

Like most other manufactories, the Matzendorf factory also produced reasonably priced undecorated everyday ware. Although such simple wares seldom survive, there are a few examples in the collections of the Solothurn museums. They also include faience with a green-blue glaze which was intended more for the kitchen than for the table (HMO 8095; AF Nr. 106).

We believe that these products could also have been made in Matzendorf. One of the reasons is that the chapter “Painting” in the manufactory’s “Arkanum” – a recipe booklet which was probably still in use around 1848 – mentions a “pretty celadon green” (Felchlin 1971, 37). Two other pieces with a similar glaze, which we have not shown here, also belong to this group: a large jug (MBS 1890.1) at the Blumenstein Museum and a double-handled jug at the Alt-Falkenstein Museum which, like HMO 8095, is only glazed on the inside.

The costrel AF Nr. 109, which was probably an example of Matzendorf “manganese-glazed brownware”, is shown here because it has a similar shape to AF Nr. 106.

Translation Sandy Hämmerle

References:

Blaettler/Schnyder 2014

Roland Blaettler/Rudolf Schnyder, CERAMICA CH II: Solothurn (Nationales Inventar der Keramik in den öffentlichen Sammlungen der Schweiz, 1500-1950), Sulgen 2014, 12-26.

Bloch 1989

Peter André Bloch, Abschied von Dr. med. Maria Felchlin 1899–1987. Oltner Neujahrsblätter 47, 1989, 80–81.

Ducret 1950

Siegfried Ducret, Die Lenzburger Fayencen und Öfen des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der schweizerischen Keramik. Aarau [1950].

Ducret 2007

Peter Ducret, Bedrucktes Steingut aus der Manufaktur Scheller in Kilchberg. Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt Nr. 119/120, 2007.

Egli 2000

Markus Egli, Grabung auf dem Fabrikgelände der ehemaligen Fayence-Manufaktur. In: Verein «Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik» (Hsg.), 200 Jahre keramische Industrie in Matzendorf und Aedermannsdorf 1798-1998. Matzendorf, 91-96.

Felchlin 1942

Maria Felchlin, Die Matzendorfer Keramik. Jahrbuch für Solothurnische Geschichte 15, 1942, 1–72.

Felchlin 1957

Maria Felchlin, Matzendorfer im Strassburger Stil. Eine neue historische solothurnische Fayence aus Matzendorf? Oltner Tagblatt 145–146, 26./27.06.1957.

Felchlin 1968

Maria Felchlin, Matzendorf in der keramischen Welt. In: 968–1968. Tausend Jahre Matzendorf, 1968, 151–213.

Felchlin 1971

Maria Felchlin, Das Arkanum der Matzendorfer Keramiken. Jahrbuch für Solothurnische Geschichte 44, 1971, 5–55.

Frei 1928

Karl Frei, Schooren-Fayencen des 19. Jahrhunderts. Jahresbericht des Schweizerischen Landesmuseums 17, 1928, 83–121.

Heege 2010

Andreas Heege, Keramik um 1800. Das historisch datierte Küchen- und Tischgeschirr von Bern, Brunngasshalde, Bern 2010.

Jegenstorf 1948

Ausstellung Schweizer Keramik des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts im Schloss Jegenstorf/Bern, Mai-August 1948. Basel 1948.

Kat. Solothurn 1847

Katalog zur Gewerbe-Ausstellung in Solothurn, eröffnet vom 9. bis zum 25. Mai 1847. Solothurn 1847.

Maggetti 2017

Marino Maggetti, Technologische Analyse eines frühen (1800-1806) Matzendorfer Steinguts. Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt 131, 2017, 105–123.

Maggetti/Galetti 2000

Marino Maggetti Marino/ Giulio Galetti, Naturwissenschaftliche Analyse der Fayence von Matzendorf. In: Verein «Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik» (Hsg.), 200 Jahre keramische Industrie in Matzendorf und Aedermannsdorf 1798-1998. Matzendorf, 99-183.

Matzendorfer Keramik 2000

Verein «Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik» (Hsg.), 200 Jahre keramische Industrie in Matzendorf und Aedermannsdorf 1798-1998. Matzendorf.

Matzendorfer Keramik 2022

Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik (Hrsg.), 100 typische Matzendorfer Keramiken 1798-1845, Matzendorf 2022.

Nyon 1958

Vingt siècles de céramique en Suisse, cat. d’exposition, Château de Nyon. Nyon 1958.

Schnyder 1990

Rudolf Schnyder, Schweizer Biedermeier-Fayencen, Schooren und Matzendorf. Sammlung Gubi Leemann. Bern 1990.

Schnyder 2008

Rudolf Schnyder, Die Ausstellung “200 Jahre Matzendorfer Keramik” von 1997 im Historischen Museum Olten. Keramikfreunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt 121, 2008, 3–66.

Schwab 1927

Fernand Schwab, Die industrielle Entwicklung des Kantons Solothurn und ihr Einfluss auf die Volkswirtschaft. Festschrift zum fünfzigjährigen Bestehen des Solothurnischen Handels- und Industrievereins. Solothurn 1927.

Strohmeier 1836

Urs Peter Strohmeier, Der Kanton Solothurn, historisch, geographisch, statistisch geschildert… Ein Hand- und Hausbuch für Kantonsbürger und Reisende. St. Gallen/Bern 1836.

Vogt 1993

Albert Vogt, Die Fayencefabrik Matzendorf in Aedermannsdorf von 1797 bis 1812. Jahrbuch für solothurnische Geschichte, 1993, 421–430.

Vogt 1995

Adolf Vogt, Unstet. Lebenslauf des Ärbeeribuebs, Chirsi- und Geschirrhausierers Peter Binz von ihm selbst erzählt. Zürich 1995.

Vogt 2000

Albert Vogt Die Geschichte der keramischen Industrie in Matzendorf und Aedermannsdorf 1798-1998. In: Verein «Freunde der Matzendorfer Keramik» (Hsg.), 200 Jahre keramische Industrie in Matzendorf und Aedermannsdorf 1798-1998. Matzendorf, 9-90.

Vogt 2003

Albert Vogt, Aedermannsdorf. Bevölkerung, Wirtschaft, Gesellschaft und Kultur im 19. Jahrhundert. Zürich 2003.