Roland Blaettler, 2019

The information that has so far been published about the two historical refined white earthenware factories that existed in Nyon and operated under some ten different company names over the course of the 19th century, has considerable gaps in it. We have tried to close these gaps as far as possible by consulting various records in the municipal archive of Nyon, for instance the minutes of municipal meetings. We have found a considerable amount of invaluable information pertaining to the most recent history in the Vaudois press, mainly thanks to the “Scriptorium” platform, which is administered by the Cantonal and University Library in Lausanne. However, in a project such as ours, the time that is allocated for such investigations is inevitably limited and we were often forced to resort to carrying out spot checks. This field of study, which obviously carries less prestige than the area of porcelain research and which still has a lot of unresolved questions, would benefit greatly from systematic archival research and from expanding the field of study.

The first attempt at outlining the history of refined white earthenware production in Nyon consisted of an unsigned two-part article that appeared in the Journal de Nyon on 6th and 11th April 1893 entitled “Industrie de Nyon: La porcelaine et la poterie à Nyon” (Nyon’s industry: porcelain and pottery in Nyon). The piece was written by Jules Michaud, the director of the Manufacture de poteries fines, a company that directly succeeded the old porcelain manufactory. At the time, Michaud based his research on the archive of the manufactory, which is today housed in the municipal archive in Nyon but has not yielded much information (ACN, R 810, Fonds Fernand Jaccard – this storage box also contained the typescript of Michaud’s brief study). It mainly comprises a series of documents pertaining to transfers of ownership of the manufactory and to the purchase of properties in the 19th century. Later documents refer exclusively to the events surrounding the hiring of Albert Jaccard as the company director in 1936.

Aloys de Molin briefly touched on the history of refined white earthenware production in Nyon (De Molin, 1904, 73 and 74). He described the reorganisation of the porcelain manufactory when Dortu and his associates made the decision in 1809 to begin producing refined white earthenware. De Molin mainly described the liquidation of the manufactory in 1813, the founding of the new company which, under the name “Bonnard et Cie”, focused exclusively on refined white earthenware, and on Jean-Louis Robillard joining the company. He too based his research on the company archive mentioned above (De Molin 1904, 74–79).

In her 1918 article entitled “Faïenceries et faïenciers de Lausanne, Nyon et Carouge” (faience manufactories and manufacturers in Lausanne, Nyon and Carouge), Thérèse Boissonnas-Baylon was interested solely in tracing the history of her ancestors, the Baylon family, who originated from the region of Lake Geneva. She was the first person to systematically search the cantonal archives of Vaud and the communal archives of Lausanne and Nyon for information about them. To this day, our knowledge of the first refined white earthenware manufactory and its development from the moment Moïse Baylon II had settled in Nyon to the moment Georges-Michel de Niedermeyer died mainly comes from her research (Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 69–83).

In 1985, Edgar Pelichet attempted to paint a complete picture of the refined white earthenware industry in Nyon, which also included the most recent history, i.e. the period up to 1978, the year in which the Manufacture de poteries fines closed. Pelichet based much of his research on his predecessors’ work and on information provided by former employees of the various companies without, however, citing his sources in any great detail. The book contains so many inaccuracies and errors that it should be treated with circumspection (Pelichet 1985/2).

We have divided the history of the different refined white earthenware manufactories that existed in Nyon between the late 18th and 20th centuries into three periods: the first manufactory – the second manufactory – the Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon SA.

The first manufactory:

– The Baylon family, 1779–1814

– Niedermeyer and Mülhauser, 1814–1829

– Fol-Lugeon, 1831–1841 (?)

The Baylon family, 1779–1814

The first production of refined white earthenware can be attributed to Moïse Baylon II (1736–1793). Having arrived in Nyon from Lausanne via a short stay in Geneva in 1779, he bought and moved into a building near the entrance to Route de Lausanne on the lakeward side (Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 71–72). From 1773 to 1775, Moïse was abroad studying the production of “modern faience” (i.e. refined white earthenware – Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 70–71). In 1784 he was granted exemption by the authorities in Bern from the “small customs duty” for transporting goods to the French- and German-speaking parts of the canton (De Molin 1904, 19–20; Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 75–76).

When he first moved to Nyon, he is most likely to have produced ordinary lead-tin-glazed faience objects. Over time, and having sourced the raw materials required, he began to produce refined white earthenware, as seems to be confirmed by a statement made by Ferdinand Müller, Dortu’s associate, to the deputy bailiff of Nyon on 5th March 1787. Müller was accused of making secret preparations to move the porcelain manufactory from Nyon to Geneva. He claimed that he had no intention of opening up a business in Geneva that was similar to the one in Nyon [i.e. a porcelain factory], but rather a “factory processing pipe clay or English clay and faience, as there was a dearth of it throughout the country; and he had moved away in an attempt to avoid competing with Monsieur Baylon’s pottery factory, which was already well established here” (De Molin 1904, 34). Baylon, however, was already making refined white earthenware in 1787 – did Müller’s claim of trying to avoid creating competition mainly refer therefore to ordinary faience?

The Nyon Castle collection (Inv. 4105) contains a journal with notes from 1828–1834, penned mainly by Antoine Louis Baylon, the grandson of Moïse II. At the time he was supporting his mother as the head of the manufactory, which had been founded by his father, Abraham Baylon, in Carouge. The journal included instructions given to him by his grandfather on how to produce refined white earthenware (Maggetti 2017). Isabelle Dumaret was the first to study the document and she concluded that Moïse would not have been able to produce refined white earthenware before 1790 if he had in fact only made his first attempts in 1789 (Dumaret 2006, 21, 65).

Incidentally, we can say that the Geneva chemist and natural scientist Henri-Albert Gosse, one of the patrons of the Geneva refined white earthenware factory in Les Pâquis, visited Moïse Baylon in June 1788 under the pretext of ordering apothecary jars. What he was really doing was discretely gathering information about Baylon’s manufacturing set-up. Gosse said that Baylon had showed him “wonderful white-blue clay” which he claimed had come from the vicinity of Nyon. Gosse, however, felt that the clay in question was more likely to have originated in Cologne or Limoges. Baylon even gave him a fired sample, “which was fairly white, but whose glass-like slip had a greenish hue if a certain thickness was exceeded” (draft letter written by Gosse to Marc-Auguste Pictet, 2nd June 1788, quoted in: Sigrist and Grange 1995, 34).

Regardless of when exactly the history of refined white earthenware in Nyon began, Moïse did not enjoy his success for very long: he died rather unexpectedly in 1793. His widow, Sophie née Dapples (1751–1814), continued to run the company, on her own at first, and from 1798 onwards with her son, Albert. When Albert too died prematurely in 1803, Sophie again ran the company on her own, as her other son, Abraham, had only a few months earlier joined Louis Herpin’s refined white earthenware factory in Carouge.

The customs exemptions obtained by the Baylon family in 1784 were explicitly granted on condition that they would mark their wares until at least 1803 (Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 76). Despite this, we are still unable to identify the Baylon marks and products from Nyon, either in relation to ordinary faience, or in terms of refined white earthenware. It is possible that they simply used an impressed mark bearing their family name “Baylon”. If this was the case, then Abraham Baylon, who took over the management of the Herpin Manufactory in Carouge in 1802, would have been forced to find a different mark for his wares. While there was a mark “BAYLON À CAROUGE”, it has only been found on four objects in total (Dumaret 2006, 62–63, Figs. 38a and 38b). The collection of the Museum in Carouge contains a number of plates, probably early works, which bear the mark “BAYLON” in very small lettering; this mark clearly differs from the most common marks from Carouge. Perhaps this lead should be followed further.

Aloys de Molin, the curator of the Archaeological Museum in Lausanne (Musée archéologique) and first historian of the Porcelain Manufactory in Nyon, appears to have been interested in this particular question. In 1903, he acquired a number of faience vessels for the Lausanne Museum with a cornflower pattern, which he rather vaguely associated with “Nyon” (MCAHL 29384; MCAHL 29385; MCAHL 29310; MHL AA.MI.989).

The Historical Museum in Vevey (Musée historique) has in its collection a plate with an indented rim, which could have originated from the same manufacturer (MHV 57).

The cornflower motif appears to have had a close connection to the faience objects from Nyon. The pieces that we are interested in clearly came from Switzerland and most probably from the Vaud region. However, that is all that can be said about them. If they were in fact made in Nyon, formal and stylistic features certainly suggest that they were probably produced after Moïse’s death.

De Molin also acquired refined white earthenware with a cornflower design, including an incomplete service which in 1906 was attributed to “Baylon” (MCAHL 30095; MCAHL 30094; MCAHL 30100; MCAHL 30110; MCAHL 30098; MCAHL 30101). However, we now believe that it was produced by an English company, even though it has not been possible to pinpoint its exact place of origin (pers. comm. Diana Edwards and John Mallet, London).

Furthermore, two compote bowls with a similar cornflower decoration, though rather rudimentary in execution, were probably acquired at the same time (MCAHL 30105). They are not manifestly consistent with any of the English or French types. The thickness of the body, the greenish colour of the slip and the slightly faded painting point to a production that had not achieved its full potential and is reminiscent of the fired sample that Moïse Baylon had given Henri-Albert Gosse during his visit in June 1788 (see above).

With regard to the other refined white earthenware objects which probably originated from the French-speaking part of Switzerland and can possibly be attributed to the Baylon family in Nyon, we would refer readers to two plates at the National Museum in Zurich with a cornflower spray on the well and four individual cornflowers on the lip (SNM LM-21910). The museum’s accession register identifies them as “late refined white earthenware from Nyon”. At one point they were attributed to the Nägeli factory in Kilchberg (Spühler 1981, Fig. 6). Rudolf Schnyder, however, did not agree.

Pelichet tried to attribute a range of polychrome glazed faience objects to the Baylon family in Nyon; however, the technical and aesthetic sophistication of these wares would have exceeded the abilities of a small local company such as theirs (Pelichet 1985/2, 15 and 16 – MHPN MH-FA-4104). Refined white earthenware of this kind was, in fact, produced by François-Antoine Anstett’s manufactory in Haguenau (Département Bas-Rhin, France).

It is worth noting that in recent years Marino Maggetti has been taking an archaeometric approach to the study of various lines of refined white earthenware production in the Lake Geneva region (Nyon, Carouge and Charmot in Jussy). The first results were published in 2017 (Maggetti and Sernels 2017). However, because there are no patterns that can clearly be attributed to the Baylon family in Nyon, it has not been possible so far to identify any of the Nyon wares in this way.

Niedermeyer and Mülhauser, 1814–1829

When Sophie Baylon-Dapples died in 1814, her son-in-law, Georges-Michel de Niedermeyer (1767–1829), took over the running of the company on behalf of his wife, Charlotte (1780–1844; Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 82). Niedermeyer was a trained musician and unfamiliar with the pottery-making industry. To compensate for his lack of expertise, he formed a partnership with Pierre Mülhauser (1779–1839), probably in 1818/19, after Mülhauser had closed down his porcelain painter’s workshop in Geneva.

During a search of the old municipal registers of Nyon, Charles Roch found evidence to show that Mülhauser had applied for the right of domicile in January 1819 (Roch 1916, 160). The partnership between Niedermeyer and Mühlhauser was dissolved in 1824. At that point, Mülhauser returned to Geneva and subsequently became artistic director of a factory that produced refined white earthenware and tiles in Migette (Doubs) (Roch 1916, 161).

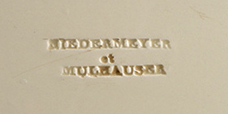

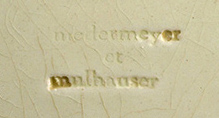

The impressed marks that are known to have been used during this period comprised both surnames, “NIEDERMEYER et MULHAUSER” (MHPN MH-2003-115) or “niedermeyer et mulhauser” (MCAHL 30460). Other marks included a “spelling error”: “NIEDEERMYER et MULHAUSER” (two examples in the collection of the Musée Ariana, Inv. 013498; 013496). We are not aware of any marks from the period before Mülhauser joined the company or after he left. This obviously raises the question whether Niedermeyer produced any wares at all during the periods in which he ran the company on his own.

Georges-Michel de Niedermeyer died on 3rd December 1829 (Gazette de Lausanne, 9th February 1830, p. 5). Almost two years after his death, his widow Charlotte put the property and buildings up for sale. The following notice was published on 23rd September 1831 in the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 7): “On Saturday, 1st October 1831, Madame Niedermeyer, née Baylon, will hold a public auction […] to sell the buildings, yards, outbuildings and gardens on the lakeshore near the port in Nyon, where the refined white earthenware factory used to be located […]. The property extends over an area of approximately 526 klafter in total”. The notice also mentions that the property included “a piece of land, approximately 120 klafter in size, which is not fit for development, known as En Collovrey [Colovrex] rière Nyon, where soil was extracted for the factory” (this was probably potting clay used for the most popular production lines).

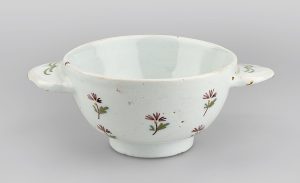

The “Niedermeyer and Mülhauser” period is represented by four objects in the collections of Nyon Castle and the Museum of Archaeology and History in Lausanne (Musée cantonal d’archéologie et d’histoire) (MHPN MH-FA-4103; MCAHL 30460; MHPN MH-FA-1625; MHPN MH-2003-115).

The Musée Ariana has six objects, five plates and one shallow dish. Three of the plates have printed motifs: two have illustrations from a fable by La Fontaine (one of them signed by the Geneva engraver Pierre Escuyer [1749–1834]), the other shows an officer cadet flanked by a shield with the Geneva coat of arms (MAG N 0068 – Pelichet 1985/2, Fig. p. 18 – N 0069 and AR 05121). The hand-painted designs, cornflowers and flower wreaths (e. g. MAG 013497 and N 0186) are clear references to the contemporaneous products from Dortu’s manufactory. The National Museum has three plates with polychrome decoration (in blue, green, yellow and purple-black) and with a vine-tendril frieze and vegetal latticework with flowers (SNM LM-62020 and LM-19566, LM-19567).

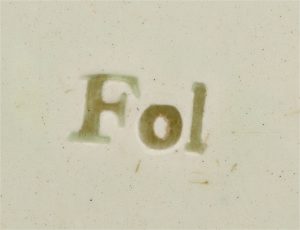

Fol-Lugeon, 1831-1841 (?)

At the auction mentioned above – which took place in 1831 and not, as Pelichet claimed (Pelichet 1985/2, 19), in 1829 – the manufactory was bought by Jean-Louis Fol, a businessman from Geneva. He and his wife, Jeanne-Marie Pernette Elisabeth, née Lugeon, had been granted the right of domicile by the municipality of Nyon in 1830 (municipal archive of Nyon [ACN], Bleu-A 51, meeting of 1st November 1830). They received their official papers on 14th January 1831 (ACN, Bleu-A 51, meeting of 28th January). As this occurred before the sale went through, it is possible that Fol had already contacted Niedermeyer’s widow in 1830 to familiarise himself with the company.

Pelichet mentions a factory “Fol et Lugeon” which, he claims, existed from 1829 onwards (Pelichet 1985/2, 19). However, the only document in the collection of the Historical and Porcelain Museum in Nyon Castle that dates from this period is a pricelist, which has the two names beside each other without the word “et” (reproduced in: Pelichet 1985/2, 19). Fol simply added his wife’s name to his own, possibly because she or her family had a stake in the business.

Pelichet dates the end of the manufactory to 1841, adding only that this was when the building was demolished. Because marked pieces from this period are extremely rare, we doubt that the production really continued for a period of ten years. Products from this period with the impressed surname “Fol” are, in fact, quite rare.

Neither Nyon Castle, nor the Museum of Archaeology and History in Lausanne have any such pieces, and the Musée Ariana has only two: an undecorated round plate (MAG R 0316) and an octagonal plate with a decorated rim and a blue transfer-printed design of rather low quality. It has a genre painting with the words “La crème” (MAG 001001). The image shows a woman with a child busily going about her chores in a rural kitchen. Even though the printed plate is not a masterpiece from a technical point of view, it does demonstrate that Jean-Louis Fol was an ambitious man. The manufactory pricelist, which was partially reproduced by Pelichet, shows that Fol made a fairly extensive range of shapes, in particular, plates, bowls and shallow dishes (Pelichet 1985/2, 19).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

Sources:

Municipal Archive of Nyon [ACN], Série Bleu A, Registres de la Municipalité – R 810, Fonds Fernand Jaccard.

Vaudois press, consulted via the Scriptorium website of the Cantonal and University Library of Lausanne

References:

Blaettler 2017

Roland Blaettler, CERAMICA CH III/1: Vaud (Nationales Inventar der Keramik in den öffentlichen Sammlungen der Schweiz, 1500-1950), Sulgen 2017, , 38-40, 266.

Boissonnas-Baylon 1918

Thérèse Boissonnas-Baylon, Faïenceries et faïenciers de Lausanne, Nyon et Carouge. Nos Anciens et leurs œuvres. Recueil genevois d’art VIII, 1918, 55-112.

De Molin 1904

Aloys de Molin, Histoire documentaire de la manufacture de porcelaine de Nyon, 1781-1813, publiée sous les auspices de la Société d’histoire de la Suisse romande et de la Société vaudoise des beaux-arts. Lausanne 1904.

Dumaret 2006

Isabelle Dumaret, Faïenceries et faïenciers à Carouge. Arts à Carouge: Céramistes et figuristes. Dictionnaire carougeois IV A. Carouge 2006, 15-253.

Maggetti 2017

Marino Maggetti, Analyse historique et technologique du carnet de notes du faïencier carougeois Antoine Louis Balyon. Revue des Amis suisses de la céramique 131, 2017, 124-157.

Maggetti et Serneels 2017

Marino Maggetti et Vincent Serneels, Étude archéométrique des terres blanches poreuses («faïences fines») des manufactures de Carouge, Jussy, Nyon et Turin. Revue des Amis suisses de la céramique 131, 158-222.

Pelichet 1985/2

Edgar Pelichet, Les charmantes faïences de Nyon. Nyon 1985.

Roch 1916

Charles A. Roch, La manufacture de porcelaine des Pâquis (Genève, 1787), Pierre Mülhauser et l’établissement de peinture sur porcelaine du Manège (Genève, 1805-1818). Indicateur d’antiquités suisses, Nouvelle série, 18/2, 1916, 154-162.

Sigrist et Grange 1995

René Sigrist et Didier Grange, La faïencerie des Pâquis. Histoire d’une expérience industrielle, 1786-1796. Genève 1995.

Spühler 1981

Theodor Spühler, Zürcher Fayence- und Steingutgeschirre aus dem “Schooren”, Kilchberg ZH von 1793 bis 1820. Ein Beitrag zur Zürcher Töpferei im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Kilchberg 1981.