Roland Blaettler 2019

The information that has so far been published about the two historical refined white earthenware factories that existed in Nyon and operated under some ten different company names over the course of the 19th century, has considerable gaps in it. We have tried to close these gaps as far as possible by consulting various records in the municipal archive of Nyon, for instance the minutes of municipal meetings. We have found a considerable amount of invaluable information pertaining to the most recent history in the Vaudois press, mainly thanks to the “Scriptorium” platform, which is administered by the Cantonal and University Library in Lausanne. However, in a project such as ours, the time that is allocated for such investigations is inevitably limited and we were often forced to resort to carrying out spot checks. This field of study, which obviously carries less prestige than the area of porcelain research and which still has a lot of unresolved questions, would benefit greatly from systematic archival research and from expanding the field of study.

The first attempt at outlining the history of refined white earthenware production in Nyon consisted of an unsigned two-part article that appeared in the Journal de Nyon on 6th and 11th April 1893 entitled “Industrie de Nyon: La porcelaine et la poterie à Nyon” (Nyon’s industry: porcelain and pottery in Nyon). The piece was written by Jules Michaud, the director of the Manufacture de poteries fines, a company that directly succeeded the old porcelain manufactory. At the time, Michaud based his research on the archive of the manufactory, which is today housed in the municipal archive in Nyon but has not yielded much information (ACN, R 810, Fonds Fernand Jaccard – this storage box also contained the typescript of Michaud’s brief study). It mainly comprises a series of documents pertaining to transfers of ownership of the manufactory and to the purchase of properties in the 19th century. Later documents refer exclusively to the events surrounding the hiring of Albert Jaccard as the company director in 1936.

Aloys de Molin briefly touched on the history of refined white earthenware production in Nyon (De Molin, 1904, 73 and 74). He described the reorganisation of the porcelain manufactory when Dortu and his associates made the decision in 1809 to begin producing refined white earthenware. De Molin mainly described the liquidation of the manufactory in 1813, the founding of the new company which, under the name “Bonnard et Cie”, focused exclusively on refined white earthenware, and on Jean-Louis Robillard joining the company. He too based his research on the company archive mentioned above (De Molin 1904, 74–79).

In her 1918 article entitled “Faïenceries et faïenciers de Lausanne, Nyon et Carouge” (faience manufactories and manufacturers in Lausanne, Nyon and Carouge), Thérèse Boissonnas-Baylon was interested solely in tracing the history of her ancestors, the Baylon family, who originated from the region of Lake Geneva. She was the first person to systematically search the cantonal archives of Vaud and the communal archives of Lausanne and Nyon for information about them. To this day, our knowledge of the first refined white earthenware manufactory and its development from the moment Moïse Baylon II had settled in Nyon to the moment Georges-Michel de Niedermeyer died mainly comes from her research (Boissonnas-Baylon 1918, 69–83).

In 1985, Edgar Pelichet attempted to paint a complete picture of the refined white earthenware industry in Nyon, which also included the most recent history, i.e. the period up to 1978, the year in which the Manufacture de poteries fines closed. Pelichet based much of his research on his predecessors’ work and on information provided by former employees of the various companies without, however, citing his sources in any great detail. The book contains so many inaccuracies and errors that it should be treated with circumspection (Pelichet 1985/2).

We have divided the history of the different refined white earthenware manufactories that existed in Nyon between the late 18th and 20th centuries into three periods: the first manufactory (see “Nyon, The refined white earthenware manufactories [1]) – the second manufactory and the Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon SA.

The second manufactory

– Dortu & Cie, 1807-1813

– Jean-André Bonnard & Cie, 1813-1814/18

– Robillard et Cie, 1818-1832/33

– The Delafléchère period, 1833 (?)-1845

– François Bonnard, 1845-1859

– Bonnard & Gonin, 1859-1860

– Manufacture de poteries S. A., 1860-1917

– The collaboration with Pflüger Frères et Cie, 1878-1883

– The collaboration with Nora Gross

Dortu & Cie, 1807-1813

Dortu & Cie, 1807-1813 in CERAMICA CH

Throughout the course of its history, the porcelain factory run by Jacob Dortu suffered from an unfortunate imbalance between the volume of wares produced and the amount sold; investments, stocks and debts steadily increased with turnover lagging behind. In 1801, the old company was dissolved and a new one set up (“Dortu, Soulier, Monod & Cie). A factory book (Livre de fabrique) compiled at the time gave a realistic assessment of the situation and recommended a shift of focus towards the “more affordable” products with the “more elaborate designs” being used “only for decorative purposes and for display in the shop” (Nyon Castle Archives, Inv. 4189). In parallel with this realignment, Jacob Dortu endeavoured to develop other, more reasonably priced products and took inspiration from the wares that were being created by the English pottery industry, in particular by Wedgwood at Etruria (Staffordshire).

From the 1790s onwards, Dortu tried to secure additional sources of income through the sale of Wedgwood products, mainly refined white earthenware and stoneware. In an attempt to safeguard the company for the future, he began to diversify his own product range by adding more reasonably priced wares in the hope of expanding the potential customer base. He mainly took inspiration from the innovations being developed by the English pottery industry.

“Terre étrusque” – The first novelty introduced by the factory was the so-called “Etruscan earth”, characterised by a very dense and fine, reddish-brown fabric. This was unglazed pottery biscuit-fired at a high temperature to make it as impermeable as possible. No chemical analysis has yet been carried out to determine how porous the product was, but one would be tempted to compare it with later industrial wares (note Andreas Heege: German-speaking archaeologists classify this type of pottery as Steingut [refined white earthenware], and it is known internationally as “English industrial ceramics” or “red stoneware”). The decorations were all added in black glaze, which gave this product line an appearance that was obviously intended to be reminiscent of Greek and Roman pottery. The figurative motifs were always designed, albeit somewhat clumsily, to look like scenes from “Antiquity”.

The 1807 account books list this production line under the umbrella term “ceramics”. More specific terms like “Egyptian pottery” or “Nankin”, which probably referred to different shades of colour, are listed under the same heading. The term “Nankin” could refer to a beige-yellow fabric, of which we have found one or two examples (Note added by Andreas Heege: this would roughly correspond to English caneware).

Examples of “terre étrusque” have rarely survived. From a formal point of view, Dortu largely used the common porcelain shapes, particularly for cups, bowls and teapots and for a small number of sugar bowls (MHPN MH-FA-3098; MHPN MH-FA-3063; MHPN MH-2013-13; MHPN MH-FA-1357; MHPN MH-FA-1280; MHPN MH-FA-3062; MHPN MH-FA-1356; MY EPM.Alim.71).

Other sugar bowls as well as different types of milk, water and cream jugs were made using newly designed shapes, which were generally more round and smoother (MHPN MH-FA-3095; MHPN MH-FA-3096; MHPN MH-FA-1267; MHPN MH-FA-3065; MHPN MH-1995-60). Applied moulded decorations in relief, for instance on the handle attachment, were rare (MHPN MH-FA-3096).

The manufactory’s account books also mention obviously more elaborate and more decorative shapes under the heading “ceramics”, including “Etruscan vases”, “vases à tremper” (?), “onion pots”, “large, horn-shaped, wall-mounted vases” and even “apothecary vessels”. Pelichet described a two-handled vase in the shape of a female mascaron, which he claimed to have found at the Museum in Nyon, but which we were not able to locate (Pelichet 1985/2, Fig. p. 25). The Swiss National Museum in Zurich has in its collection an urn-shaped jug with a rounded body, a base and a tubular spout, which is identified there as a “coffee pot” (SNM LM-24253). We would be more inclined to identify it as a “chevrette” (apothecary vessel, syrup jar) based on a similar refined white earthenware chevrette that was recently discovered in the Reber collection (Unil MH-RE-522). The Zurich “coffee pot” is very heavy, too heavy, in our opinion, to have served as a item of table ware. If our opinion was to be confirmed, it would be the first example of an apothecary vessel made of “terre étrusque” and thus unique.

The account books only contain information for the years 1807 and 1808. Given the quantities listed it is obvious that this line of production was short-lived.

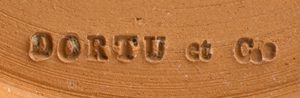

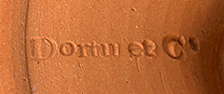

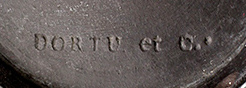

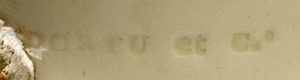

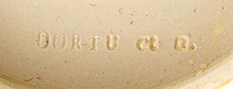

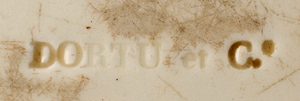

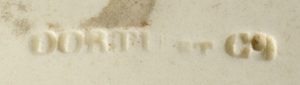

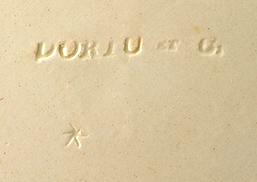

The “terre étrusque” vessels generally bore the impressed marks “DORTU et Cie” (MHPN MH-FA-1280) or “Dortu et C.e” (MHPN MH-FA-3095).

Industrial black ware (Grès fin noir) – Dortu also attempted to produce black stoneware (industrial black ware), which was stained throughout and whose shapes were inspired by Wedgwood’s black basaltes or industrial ceramics (MHPN MH-FA-1365; MHPN MH-FA-1364). Its production appears to have commenced at roughly the same time as that of the “terres étrusques”. Only a few examples have survived and, although they were well made and are quite beautiful, production probably ceased relatively soon after it began because the manufacturing process was too complex and costly. “Black ceramics” are occasionally mentioned in the account books, and most appear to have had “red decorations”.

A small number of impressed marks can be found on black stoneware, all of the “DORTU et C.e” type (MHPN MH-FA-1365).

Refined white earthenware – Dortu’s main goal appears to have been to imitate creamware, the prize product of English pottery making at the time (labelled by the factory as “terre de pipe”/“pipe clay”, also known as white-bodied industrial earthenware). According to a report compiled when the company was dissolved in 1813 (see below), production only became profitable in 1809 after several years of costly experiments.

In the meantime, the company had once again been restructured: on 1st January 1809, the company was replaced by a public limited company. Dated 9th December 1808, the statutes of the company “Dortu, Soulier, Doret & Cie” clearly defined its purpose: to produce and sell porcelain, “terre de pipe” [pipe clay] and “poteries étrusques” [Etruscan pottery] (Bonnard 1934/1, 115).

The results of Dortu’s endeavours were very convincing and his products were comparable in every way to the best refined white earthenware available in Europe at the time. He also went out of his way to make his products look very attractive.

Some of his shapes were rather complex, such as baskets with openwork bodies, vases with mascaron-shaped handles and cornet vases (MHPN MH-FA-1053; MBS 1908.38).

As for painted designs, he developed a series of motifs ranging from plain vegetal friezes – inspired by selected Wedgwood designs (MHPN MH-FA-3070) – to monochrome landscapes of a type widely produced by French factories of the period (MHPN MH-FA-4102). He also created designs that testified to a remarkable mastery of polychrome painting that would not be achieved by any other 19th century factory in Nyon (MHPN MH-FA-1053; MHPN MH-FA-4100).

Dortu also used transfer-printed decorations, probably before any of his rivals in Carouge, with Swiss traditional costumes or views of Roman monuments (MHPN MH-FA-2288; MHPN MH-FA-2289; MHPN MH-FA-1803; MHPN MH-FA-2290).

The inventory that was compiled when the factory was liquidated in January 1813 listed a stock of refined white earthenware valued at more than 25,361 livres, “terres étrusques” worth 3585 livres and porcelain worth 85,326 livres. It is generally believed that the porcelain objects were the result of over four years of production (Nyon Castle Archives, inv. 4193).

That same year Jacob Dortu moved to Carouge where he set up a new company with his son-in-law, Bernard Henri Veret, and Veret’s nephew, Auguste Bouverot. Initially, the production in Carouge was very similar to that in Nyon. In many cases it is only thanks to the impressed marks (“Dortu et C.e” in Nyon – “Dortu, V. et B.” or “Dortu, Veret et Ce” in Carouge) that we can differentiate between the products from the two locations.

Various types of vessels with small bases such as bowls, cups or cream jugs, however, were not marked in either of the places of manufacture. In these cases, it is not always possible to determine where they were made. We are not sure, for instance, if a cup with a cornflower design, which probably belonged to the same production line as similar motifs on porcelain (MCAHL 31645), was actually made in Nyon.

It was definitely produced by Dortu, but the motif in question was used in exactly the same way at his new manufactory in Carouge (MCAHL 30018bis; MHPN MH-FA-1826; MCAHL 29314bis; MCAHL 30072; MCAHL 30080). Pieces that bear both Dortu’s mark from Nyon and a cornflower pattern are rather rare; the National Museum has two examples in its collection: a cylindrical teapot and an urn-shaped sugar box on a stand (SNM LM-22841.1; LM-22841.2).

Dortu’s refined white earthenware usually bore the same marks as the “terres étrusques”: “Dortu et C.e” (MHPN MH-FA-3180) or “DORTU et C.e” (MHPN MH-FA-3070). Other variations worth noting are “DORTU ET C.e” (MHPN MH-FA-1803), “DORTU et C.” (MHPN MH-FA-4100) and “DORTU ET C.” (upper case cursive script) (MHPN MH-FA-4101).

The last mark mentioned was only used on plates and was often accompanied by stamped production marks in the shape of a circle or asterisk. At this stage of the research, we do not have enough reference material to understand how the different marks were used.

Jean-André Bonnard & Cie, 1813-1814/1818

Jean-André Bonnard & Cie, 1813-1814/1818 in CERAMICA CH

On 31st January 1813, the shareholders, faced with the rather desperate financial situation the porcelain, “terre étrusque” and pipe-clay factory found itself in, tasked a commission of five people led by Pierre-Louis Roguin de Bons (1756-1840) to compile a report and formulate a plan for the future direction of the company. The commission concluded that, in order to safeguard the pottery industry in Nyon, it would be necessary to dissolve the company “Dortu, Solier, Doret & Cie” and set up a new entity that would focus exclusively on manufacturing refined white earthenware. On 3rd March 1813, a plenary assembly of the shareholders agreed to drop the brand name “Dortu et C.e” and replace it either with “Commandite de Nyon” or with the shortened form “Comte de Nyon” on all future products. We have never encountered this mark, however, and it appears that it was never actually used.

By April, the manufactory, along with the trade secret, had already been sold to Jean-François Delafléchère, Pierre-Louis Roguin de Bons and Jean-André Bonnard (1780–1859) (Nyon Castle Archives, 1813 liquidation records; De Molin 1904, 74-79). On 23rd May 1813, the shareholders acknowledged the sale of the company to a private limited partnership set up by Jean-François Delafléchère, Jean-André Bonnard and his father Moïse Bonnard, Pierre-Louis Roguin de Bons, Augustin-Alexandre Bonnard and André-Urbain Delafléchère de Beausobre (De Molin 1904, 82 – The new owners’ identities were recorded in two separate notarial deeds dated 1814 and 1817 respectively documenting the sale of land: Nyon Municipal Archives [ACN], R 810).

Jacob Dortu, as the main manufacturer, was extremely reluctant to part with his trade secret but was eventually persuaded by the members of the commission, who argued that he had only been able to develop his processes thanks to the financial backing of the company. In exchange for 200 Louis d’Or, he eventually handed over his trade secret. Once the business was concluded, Dortu left Nyon in 1813 and moved to Carouge.

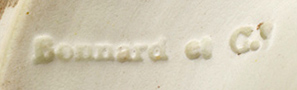

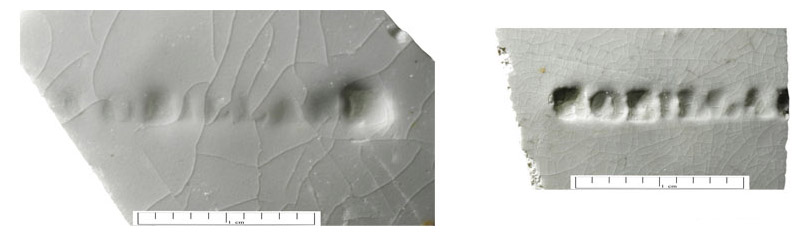

The trade secret was entrusted to Jean-André Bonnard, who also took over the running of the company. Its new name was “Jean-André Bonnard & Cie” and the impressed mark associated with it was “Bonnard et C.e” (MHPN MH-FA-3183; MHPN MH-FA-10015).

Contrary to Pelichet’s claim, not all products from the “Bonnard et Cie” era were undecorated. The factory did, in fact, continue Dortu’s ornamental style, albeit in simpler form: monochrome vegetal borders (MHPN MH-FA-4070; MHPN MH-FA-4418A) or cornflowers without the brownish-ochre colour on the stems (MHPN MH-2009-7B).

The new company also had an innovative side in that its products included ceramics with openwork decoration and pieces with reddish-brown underglaze brushwork decoration (MHPN MH-FA-10016; MHPN MH-FA-10017); this technique was later adopted by Robillard.

The manufactory also continued to produce complex models such as woven baskets, which were in every way comparable to those from Dortu’s period (MAG 016840 and 016841; Valangin 9361b VAL).

Robillard et Cie, 1818-1832/33

Robillard et Cie, 1818-1832/33 in CERAMICA CH

On 17th December 1814, the company “Jean-André Bonnard et Cie” purchased a neighbouring plot of land to extend its business premises. Besides the co-owners already mentioned, the deed also listed a Jean-Jacques-Louis Robillard from Geneva (ACN, R 810).

Robillard, a Geneva-born French businessman, moved to Nyon on 21st June 1813 (Pelichet 1985/2, 27). De Molin believed that the strain of running the factory had become too much for Bonnard and that Robillard had “effectively taken over as manager” of the company in 1814 (De Molin 1904, 84-85). We do not know if de Molin had other sources or if he simply drew his own conclusions from the document mentioned above. Did the change of leadership occur between 17th and 31st December 1814? A deed dated 2nd June 1818 shows that Moïse and Jean-André Bonnard sold their shares (each owned one sixth of the company) to the four remaining co-owners: “André-Urbain De La Fléchère de Beausobre (1754-1832), Pierre-Louis Roguin de Bons (1756-1840), Jean-François De La Fléchère and Jean-Jacques-Louis Robillard … co-owners” (De Molin 1904, 85; ACN, R 810). Augustin-Alexandre Bonnard-Crousaz was no longer named in the deed, having obviously withdrawn before the transaction took place, as each partner owned one sixth share of the property at the time of the sale.

Contrary to what de Molin and later Pelichet hypothesised, it is quite possible that the company name was not changed until the moment when Jean-André Bonnard left the partnership. The deed in question states: “This contract of surety does not in any way affect the personally written and signed discharge of the company Jean André Bonnard & Compagnie through declarations of suretyship, disruptions, evictions and other legal clauses”.

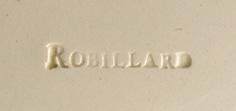

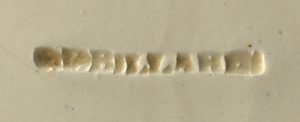

The company name was changed once again, this time to “Louis Robillard & Compagnie” and the new factory mark consisted of the director’s name “ROBILLARD”.

According to Jules Michaud (see above), the company did well under the new management. On 28th August 1821, the following notice was published in the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 3): “In the absence of a warehouse in this town to store their products, which are widely known to be of excellent quality, Monsieurs L. Robillard & co., owners and directors of the former porcelain and pipe-clay factory in Nyon would like to advise their customers in Payerne and its surroundings that orders can be placed directly with them, and that they will fulfil these orders with the utmost care, and at a cost and conditions that are extremely favourable to their customers”.

By 1824, the entrepreneurs behind Robillard et Cie from Nyon felt the time was right to begin a new venture abroad. In 1822, Jean-Marie and Joseph Marie Charmot, two well-known figures from Sciez near Thonon (Haute-Savoie), had been awarded a royal warrant by the King of Sardinia to produce refined white earthenware and faience at their workshop in a hamlet called Jussy (Maire 2008, 437). Because the Charmot brothers did not have the technical skills to achieve this, they reached out to Robillard et Cie and offered a limited partnership “in exchange for their industrial secrets”.

On 13th March 1824, Robillard, who had been given power of attorney, and the Charmot brothers signed an agreement. Pelichet has a photograph of the document which is signed by all parties and dated 24th April. It lists all the modalities of the contract (Pelichet 1985/2, 30 and 31). The entrepreneurs from Nyon invested 40,000 Savoie Livres in exchange for a share of the profits. De Molin mentions another document dated 1826 which shows that the Charmot brothers were at that stage asking for a period of grace on their interest repayments and deduces from this that the business was not going too well (De Molin 1904, 86). The company, however, was probably no worse off than most similar businesses at the time. In fact, the Savoy manufactory remained in operation until 1839, when it closed down. It reopened a year later under a slightly different company name. It closed permanently in 1848 (Maire 2008, 440). It is not known when the investors from the Canton of Vaud resigned from the business.

In terms of quality, the products from Jussy are just as good as the refined white earthenware from Nyon (see for example MHPN MH-FA-466; MHL AA.MI.2265; Unil MH-RE-331; Unil MH-RE-332; Unil MH-RE-333).

Getting back to Nyon itself, Aloys de Molin states that the circumstances of Robillard’s withdrawal from the factory were rather mysterious and points to the fact that “he was still running it with much success in 1832” (De Molin 1904, 86). He was probably basing this assumption on the Almanach pour le commerce et l’industrie, which was published in Lausanne in 1832 and which mentions the company under the name “L. Robillard et Compe, fabrique de terre de pipes” [L. Robillard and co., pipe-clay factory] (p. 77). This almanac was published under the patronage of the Bazar Vaudois, which had been founded not long before that by Louis Pflüger and Benjamin Corbaz. We should mention that Robillard was one of the first manufacturers from the Vaud region to offer his products for sale at the Bazar (Le Conteur vaudois, No. 46, 1881, 1–2). Pelichet was more direct, simply stating that Robillard had withdrawn from the business in 1832 (Pelichet 1985/2, 27). Here too he neglected to cite any of his sources, and we must therefore assume that the claim was the result of a somewhat bold interpretation of the passage from de Molin’s book cited above. In reality, the situation was a little more complicated. On 11th October 1833, the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 5) published a notice stating that the commissary general of customs was reducing import duties on raw materials and abolishing export duties from the canton on industrial products for several companies, including… “MM. Robillard et Ce à Nion [sic], fabrique de poterie fine”. Does this mean that the company name was still in use in 1833? Would the customs authorities not have been informed if the name had been changed? It is also possible that André-Urbain Delafléchère’s death in 1832 prompted Robillard’s withdrawal for one reason or another.

At any rate, de Molin was of the opinion that Robillard’s withdrawal dealt a heavy if not fatal blow to the company (De Molin 1904, 86). In a history of the factory in Nyon published in the Gazette de Lausanne on 22nd March 1879 (p. 3), the journalist, who probably based his statements on information he received from the then director of the company, Jules Michaud, praised Robillard, “whose attention to detail, steadfastness, sense of order and frugality gave the company a reputation for being honest, which is still remembered by the older generation of people in Nyon. Monsieur Robillard retired, leaving his successors with a flourishing industry and detailed information about the manufacturing process which, however, did not prevent them from making poor business decisions”.

The products from the Robillard era are naturally better represented among the refined white earthenware from Nyon that we have been able to study than those from previous periods, given that Robillard lived a relatively long life. Brushwork decoration initially continued along the same trajectory as it had before, with vegetal friezes and cornflower designs (MAF C 455; MHPN MH-FA-4664; MHPN MH-FA-4665; MHPN MH-FA-4668; MHPN MH-FA-4666O und -4667L; MHPN MH-FA-4669D; MHPN MH-FA-2806; MHPN MH-FA-1802; MHPN MH-FA-3882; MHPN MH-FA-3882bis).

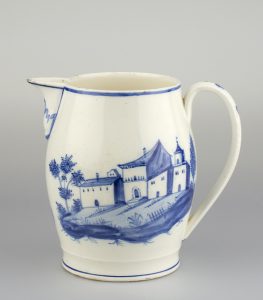

Robillard continued Bonnard’s designs using reddish-brown slip but exaggerated them somewhat (MHPN MH-2005-2C; MHPN MH-2005-2A; MHPN MH-2005-2B) and also revived the monochrome landscapes (now in blue), and either enclosed them in circular medallions or dispensed with the frames entirely.

The painting of some of the motifs was executed with extraordinary care (MHPN MH-FA-3905; MHPN MH-FA-4733; MHPN MH-FA-4734; MHPN MH-FA-4735; MHPN MH-FA-4736), while others seem more impulsive in style (MHPN MH-FA-3387; MHPN MH-FA-1823) and yet others demonstrated an almost unrestrained freedom in how the brush was used (MHPN MH-FA-3389; MHPN MH-FA-4074).

One could be tempted to date the first examples as the earliest, if it was not for this small milk jug; it has a very carefully painted design on the one hand and a mark which we generally associate with a later period on the other (MHPN MH-FA-1822).

It was clearly Robillard who took the motif “Aux Immorelles/strawflower”, which was ordinarily used on porcelain, and introduced it to the refined white earthenware repertoire (MHPN MH-2015-527 –see another small milk jug at MAG 018469).

Robillard also reintroduced transfer-printed designs (we are not aware of any examples of this type from the Bonnard period), with classic depictions of Swiss traditional costumes modelled on Swiss painters like Franz Hegi (MHPN MH-1999-104; MHPN HM-2009-6) or Swiss landscape views inspired by the lithographic illustrations in the book by Désiré-Raoul Rochette et al. entitled Lettres sur la Suisse, which was published between 1823 and 1832 (MHPN MH-FA-3212). The Musée Ariana has in its collection a plate with a depiction of the Rhine Falls from the same series (MAG 018464).

As for the shapes, Robillard extended the range of tureens (MHPN MH-FA-1658; MHPN MH-2015-366; MHPN MH-FA-4073) and hot water plates (MHPN MH-FA-3882; MHPN MH-2003-117; MHPN MH-FA-3184) considerably. The Swiss National Museum in Zurich has in its collection an elegant oval tureen on a stand with high handles (SNM LM-86565). The manufactory continued to produce some of the tried and tested shapes, for instance the obligatory baskets, whose shapes were almost identical to those from preceding periods (MHPN MH-FA-3186; Valangin 9360b and 9361a VAL; MAHN AA 1406 and 1407). Alongside a cylindrical teapot taken from the porcelain range, Robillard introduced a more modern, round-bodied version with an everted rim (MHPN MH-FA-3111).

The Musée Ariana has in its collection two types of coffee pot on a pedestal base with a pear- or egg-shaped body and an everted rim (MAG 015131 and AR 12605), a nightlight (MAG 014818) and a small oval dish with applied decoration modelled on an older type from the porcelain factory (MAG 018461– for the porcelain form see MHPN MH-PO-1544).

Pelichet mentions a printed pricelist for Robillard’s period in the collection of the museum in Nyon, but we were not able to locate it. According to Pelichet, the list contained the more conventional products on the one hand and toothpick holders, holy water fonts, spittoons, painters’ palettes as well as busts of Voltaire and Rousseau on the other (see MHPN MH-FA-1663; MHPN MH-FA-1495 – Pelichet 1985/2, 26-28).

Période Delafléchère, 1833 (?)-1845

Période Delafléchère, 1833 (?)-1845 in CERAMICA CH

Following the death of André-Urbain Delafléchère de Beausobre in 1832 and the departure of Robillard, the company was divided up between Pierre-Louis Roguin de Bons, Jean-François Delafléchère and the heirs of André-Urbain: Jules-François, one of Jean-François’ cousins, and Emmanuel-Théodore Delafléchère. This is confirmed by a letter dated 8th April 1840 addressed to Antoine Abram Hegg, councillor in Nyon. It mentions a property swap and states that the four people listed above were “joint owners of the factory and its associated buildings” (ACN, R 810). Roguin de Bons died a few months later, on 11th November 1840. Because his heirs were apparently related by marriage to the Delafléchère family (see below), we can definitively state that the company had now become a family business.

According to Pelichet, who again refrains from citing his sources, the factory was run by Jules-François Delafléchère after Robillard had departed (Pelichet 1985/2, 32). Because we have not been able to find any evidence of a specific company name, we are using the slightly vague term “Delafléchère era” here.

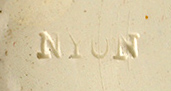

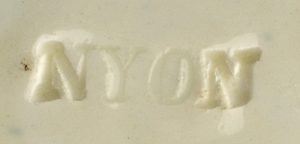

Derselbe Autor glaubt auch, dass zu diesem Zeitpunkt die neue Marke «NYON» eingeführt wurde. Nach unserem heutigen Kenntnisstand sind wir mit dieser Arbeitshypothese einverstanden.

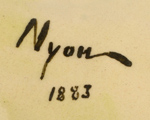

Pelichet also believed that this was the moment in which the new mark “NYON” was introduced. Based on our current state of knowledge, we would agree with this as a working hypothesis. While searching the archives of the Historical and Porcelain Museum in Nyon (Musée historique et des porcelains de Nyon MHPN), we came across the workshop journal of Engineer Frédéric Gonin, who later became the head of the Nyon manufactory. It contained the following mysterious note in reference to a test firing of yellow cookware: “In Casamène we fired…”. Casamène was an industrial estate in a suburb of Besançon (Doubs, France), where refined white earthenware and other ceramics were produced; the note suggests that Gonin worked at this manufactory. A short chapter about the factory in a book about refined white earthenware and the refined white earthenware factories in the Franche-Comté region by Louis and Suzanne de Buyer (De Buyer et de Buyer 1983) not only confirms this but actually talks about quite an important link between the entrepreneurs in Nyon and the refined white earthenware factory in Besançon, which has to date never been mentioned from a Swiss point of view. According to the book, the Casamène Manufactory (the first of its kind in this location) was founded by two entrepreneurs from Nyon in 1841: “Mr de Bons, a former governor of the Canton of Vaud, and Mr de Flachère [sic]” (de Buyer and de Buyer 1983, 103 – the authors also refer to an official act initialled on 2nd July 1841 in Besançon).

While de Bons was perhaps involved in setting up the project, he was no longer part of its implementation: he died on 11th November 1840. A few years after taking over the running of the company in Nyon, some of the leading figures involved in the factory in Vaud seem to have opened a second manufactory on French soil (for examples of the wares produced in Besançon see MHPN MH-FA-3876-1; MHPN MH-FA-3876-2; MHPN MH-FA-3876-3; MHL AA.MI.991, MPE No. 22). Frédéric Gonin himself is mentioned as the “technical advisor” (de Buyer and de Buyer 1983, 104). The enterprise appears to have been very successful: according to de Buyer, it employed 120 workers in 1844.

The refined white earthenware products from Casamène have black-brown and sometimes even two-tone printed decorations. The latter are plates with black-brown motifs on the well and blue or red ones on the lip. One of the examples reproduced by the de Buyers is a plate with a view of Thun on its well. It is identical to one that appeared more or less at the same time on products from Nyon (MHPN MH-FA-535; MHPN MH-FA-10023B).

While the decorations on the lips are different, the motif in the centre appears to have come from the same engraving. Apparently, a series of motifs or copperplates circulated between Nyon and Casamène.

This also explains the presence in Nyon of rather exotic illustrations that refer to the lives of French soldiers, for example the cross of the Legion of Honour (La Croix d’honneur; MHPN MH-2003-127; MHPN MH-FA-10022; MHPN MH-FA-1827) or a humorous depiction of everyday life in Napoleon’s army, a motif that was widely used to adorn French wares (MHPN MH-2003-126).

A paragraph entitled “Casamène” in the catalogue of the Museum in Sèvres by Alexandre Brongniart and Denis-Désiré Riocreux reads: “Three examples of perfect refined white earthenware with a hard glaze based on boron compounds, produced under the direction of H. Gonin, civil engineer, 1844”. A plate with “arabesque friezes and a view of Zurich” and two “English cups decorated with flowers and landscapes” can be added to this little group of objects. All decorative motifs were printed in blue and black (Brongniart and Riocreux 1845, cat. no. 21). The reference to people from Nyon being involved in creating this manufactory and the ties between the two places of manufacture are clearly deserving of more in-depth research, but this would go beyond the remit of our work.

Jean-François Delafléchère died in early February 1845. The Feuille d’Avis de Lausanne dated 4th February 1845 (p. 1) published a notice by the Nyon District Court recording the death of the former lawyer and scheduling the deadlines for submissions made under the “Benefit of Inventory”. Contrary to what de Molin writes (De Molin 1904, 86), it was Jean-François, and not Jules-François Delafléchère, who died in 1845. Pelichet, on the other hand, mentions that both cousins, Jean-François and Jules-François, were declared bankrupt (Pelichet 1985/2, 32). The fact is that the Delafléchère family was in a state of collapse.

On 19th August 1845, the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 4) announced that “the commissions of the district court of Nyon, which have been tasked with liquidating the assets of the three shares held by Jean-François Delafléchère, Emmanuel-Théodore Delafléchère and Jules-François Delafléchère, will put up for public auction the beautiful premises of the Manufacture de porcelaine et de terre de pipe de Nyon […]. The preliminary auction will be held on 1st September […] and the final auction will be held the next day”. Following the auctions, the sale of the factory was notarised on 11th November 1845 in the presence of the judges who represented the shares of Jules-François, Emmanuel and the late Jean-François De La Fléchère. The judges “acted as attorneys for Françoise-Louise, the daughter of the late Georges-Augustin Roguin and ex-wife of Jean-François De La Fléchère, and for Anne-Louise De La Fléchère, the daughter of the late André-Urbain De La Fléchère.” These parties “sold the pipe-clay factory in Nyon to François Bonnard, the son of Jean-André, who attended in person and accepted the sale […] following the auction” (ACN, R 810).

The bankruptcy of the Delafléchère family in Nyon also brought to an end their adventure in the Franche-Comté region. The Casamène Manufactory was, in fact, sold in 1845 and changed its production under the new ownership (de Buyer and de Buyer 1983, 105).

As mentioned above, the actual name of the company in the “Delafléchère era” is not known. As far as the factory mark is concerned, the impressed mark “NYON” may be relevant for this period.

A small milk jug (MHPN MH-FA-1822) offers an interesting clue in this respect. In terms of the quality of its fabric and the painted design, the vessel continues the trajectory that began with the ceramics with carefully painted landscapes and “Robillard” marks mentioned above. This transition piece does, in fact, bear the “NYON” mark.

The Delafléchère manufactory also used monochrome landscape designs which were not as carefully painted (MHPN MH-FA-4390A; MHPN MH-FA-4390B; MHPN MH-FA-4390C; MHPN MH-FA-4390D) and were thus reminiscent of the poorer quality of the painted landscapes from the Robillard era (MHPN MH-FA-3387; MHPN MH-FA-1823; MHPN MH-FA-3389; MHPN MH-FA-4074).

They were followed by landscapes that were sometimes framed in plant motifs and included architectural elements (MHPN MH-FA-1820; MHPN MH-FA-1810; MHPN MH-FA-1807; MHPN MH-FA-1815; MHPN MH-FA-1811; MHPN MH-FA-1818; MHPN MH-FA-1809; MHPN MH-FA-1813; MHPN MH-FA-3981; MHPN MH-FA-4743) reminiscent of motifs used by Baylon in Carouge (see e.g. Dumaret 2006, Figs. 4 and 5). However, the buildings on the pieces from Nyon did not show as much detail; note the triangular roofs, in particular, that violate all rules of perspective (MHPN MH-FA-1809; MHPN MH-FA-1821).

The manufactory also produced transfer-printed decorations, some of which revisited motifs from the Robillard period (ML 2012-20-1-B; ML 2012-20-1-C; ML 2012-20-1-D; ML 2012-20-1-E; ML 2012-20-1-A). These motifs, views of Swiss landscapes, particularly around Lake Geneva, and French military scenes, were printed both on classic plates with flat bases and on new shapes such as small milk jugs with polygonal bodies (MHPN MH-FA-1376).

It was probably just after 1840 that a new generation of transfer-printed designs were developed; they sometimes used the same central motifs but also had relatively complex designs on the lips (MHPN MH-FA-4112; MHPN MH-FA-3907; MHPN MH-FA-535; MCAHL 31920; MCAHL 31919; MHPN MH-1998-106; MHPN MH-1998-104; MHPN MH-FA-3908; MHPN MH-1998-105; MHPN MH-1998-108; MHPN MH-FA-3113; MHPN MH-1998-109; MHPN MH-1998-33; MHPN MH-FA-10022; MHPN MH-FA-1827; MHPN MH-2003-126; MHL AA. 46 .B.3; MHL AA.46.B.4). These designs are reminiscent of the ones produced by the manufactory in Casamène (see above and MHPN MH-FA-535).

The profiles of these plates were redesigned completely: the base was sunken and the plate rested on a ledge formed by the extension of the exterior wall.

One of the new models also had vertical ribbing on the lip (MHPN MH-FA-2917; MHPN MH-FA-10024; MHPN MH-FA-10025; MHPN MH-FA-10023B). The profiles of these pieces overall were refined and more precisely made than the earlier plates had been. These improvements can probably be attributed to the expertise gained by the engineer Frédéric Gonin in Casamène.

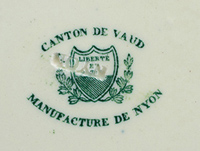

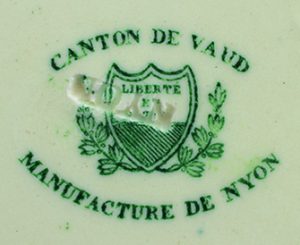

These pieces had a new mark in the same colour as the design which was often added next to the traditional impressed “NYON” mark. It consisted of a shield with the coat of arms of Vaud framed by the words “Canton de Vaud – Manufacture de Nyon”. There were two versions of the mark; in one version the shield was flanked by ears of wheat (MHPN MH-FA-3907), in the other by laurel branches (MHPN MH-1998-104). The glaze on the pieces with the green designs always had a distinctly yellow hue (e.g. MHPN MH-1998-105; MHPN MH-FA-1827).

While in the collections in Vaud this new production line is mainly represented by plates, the Musée Ariana also has a number of pear-shaped small milk jugs with polygonal bodies (MAG 001003, 018479), an urn-shaped sugar bowl with a curved lid (MAG 013490), an egg-shaped coffeepot on a pedestal with an everted rim (MAG 014447) and bell-shaped cups with bevelled bodies and pointed handles (MAG 014917 and 018477).

A cup and saucer can be found in the collection of the Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel (MAHN AA 1687 and 1688), while the National Museum has in its collection a teapot with a dodecagonal body (SNM LM-17976). It should be noted than none of these shapes bear the new printed mark; it appears to have been used on plates only.

François Bonnard, 1845-1859

As mentioned, the Delafléchère factory was put up for public auction and bought by François Bonnard, the son of Jean-André Bonnard, one of the company’s former co-owners, on 11th November 1845. Pelichet states that Bonnard formed a partnership with Henri Veret for a short while, using the mark “Bonnard & Veret” (Pelichet 1985/2, 34). To date, we have not encountered any vessels bearing this mark, nor have we come across any documents referring to this partnership.

A notice in the Gazette de Genève dated 11th May 1847 (p. 4) provides food for thought: “Pottery and faience factory in Nyon for rent. We suggest investing in shares of 300 French francs to make a profit in support of the production of white and brown faience and Paris-style cookware. The factory will be run by a shareholder”. What we can say for certain is that the factory run by François Bonnard was doing quite well in 1848, as it won a silver medal at the Second Swiss Industry Exhibition in Bern, where it was registered as exhibitor no. 381. The technical report published by Ludwig Stantz after the exhibition reads: “The crockery from Nyon is more attractive than that from Zurich [the Scheller factory], and it is even better made than that from Baden. […] It is bright white, the fabric is heavier but has a nice tone. The plates have ‘porcelain shapes’ [with a ledge or sunken base]” (Frei 1951, 6 and 7).

The Historical and Porcelain Museum in Nyon Castle (MHPN) houses copies of an invoice and a cover letter to a merchant called Germain Lugon in Martigny dated February 1853. The letterhead on the invoice reads “Manufacture de terre de pipe de François Bonnard” [Pipe-clay Manufactory François Bonnard]. The consignment apparently consisted mainly of undecorated pieces. Signed by a Fritz Bonnard (probably an abbreviation of François), the letter, on the other hand, refers to various decorated pieces in his range of products “various pieces with two small blue and green depictions of bouquets of flowers […] I also add blue or green network patterns on the rims of the pieces […] I also produce lithographic printed decorations and have sold several in recent years but they are currently not available. I will be reinstating this production within the next month.” As a side note, we can say that the order that Lugon placed on 7th February was not filled until 23rd May (date of dispatch). The factory does not appear to have been very efficient. Moreover, the products that were offered to the retailer were admittedly rather unattractive: brushwork decorations of a minimalist nature, to put it mildly, and printed motifs that were executed without much care (see below).

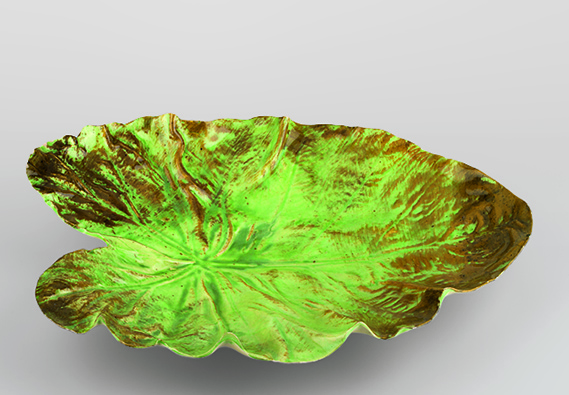

François Bonnard also participated in the third Swiss exhibition in Bern in 1857. Assigned the exhibitor number 796 he offered a “large range of white crockery, some of which bore printed decoration” (Messerli Bolliger 1991, 16). All three Swiss refined white earthenware manufacturers that were represented at the exhibition – Scheller in Zurich (Kilchberg), Antoine Baylon in Carouge and Bonnard in Nyon – were rather harshly assessed by Pompey Bolley, the author of the technical report; he considered their products to be inferior to those of their English and even their German competitors, who were producing harder and whiter refined white earthenware. Plates were made both in the “faience shape” (without footrings) and in the “porcelain shape” (with footrings). In terms of the designs, the only products that were really of sufficient quality were those offered by Scheller. Bolley did praise the two manufacturers from the French-speaking part of Switzerland for their fish dishes. He also acknowledged the progress that all three of the Swiss manufacturers had made, particularly with regard to the execution of brushwork and transfer-printed designs (Frei 1952, 3-4). That year, Bonnard and Baylon had to settle for an honorary mention while Scheller took home a silver medal.

An article about the refined white earthenware manufactory published in the Gazette de Lausanne on 22nd March 1879 (p. 3), summarises the François Bonnard period as follows: “Repurchased in 1845, the manufactory made modest but considerable progress until 1859 […]”. On 25th March, the same newspaper (p. 2) published the reaction of an anonymous reader – probably none other than Jules Michaud, the director of the Manufacture de poteries fines – who bemoaned the fact that the author had neglected to mention François Bonnard, “the man who ran the enterprise from 1845 until 1859 [… and], besides continuing the production of white crockery […] had introduced a special range of brown cookware with a glossy glaze [terre à cuire brune avec vernis brillant, nowadays we would use the term cookware with black-brown manganese glaze; note by Andreas Heege], as well as blue transfer-printed decoration, albeit on a rather small scale […]”. The reply from another anonymous reader, probably Jules Michaud again, stated that “F. Bonnard had the courage (probably in 1850) to make another attempt at producing porcelain in Nyon. He even made some test firings, but since the results were not very convincing, he discontinued the production” (Gazette de Lausanne, 29th March 1879, 3).

It is quite difficult to identify products from François Bonnard’s period. No marks have come to light that can be attributed to him. We can only assume that he continued to use his predecessors’ mark “NYON”, which is also known to have continued to exist in the next iteration of the company. Is it possible that Bonnard put objects on display at the 1848 exhibition that came from his stock but had been made previously? We do not know of any examples that bear the brushwork decorations he mentioned in his letter in 1853. It is possible that some of the undecorated faience objects that bear the “NYON” mark came from his production.

Bonnard & Gonin, 1859-1860

Bonnard & Gonin, 1859-1860 in CERAMICA CH

Frédéric Gonin (1819–1864), about whom very little is known, played an outstanding role in the development of the pottery industry in Nyon, although it is not yet clear quite how big his influence was, as indicated above in relation to the links between certain entrepreneurs from Nyon and the factory in Besançon-Casamène. He is sometimes described as a civil engineer, and sometimes as an industrial chemist. We do know that Gonin attended the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures (Central School of Arts and Manufactories) in Paris where he was given an introduction to ceramic technology (see below). He subsequently worked at various pottery factories in France, including the manufactory in Casamène, where he came into contact with the people in charge of the Delafléchère business in Nyon. His workshop journal recorded his presence in Nyon as early as 1858.

As for his relationship with François Bonnard, de Molin only states that Bonnard ran the factory in partnership with Gonin, a civil engineer from Lausanne, until 1860 (De Molin 1904, 86). Pelichet, by contrast, claims that both men “very quickly” secured managerial positions within the company. In his account, Gonin is described as a nephew of Louis Gonet, a banker from Nyon, who allegedly helped Frédéric Gonin and his father Benjamin gain a share of the company as early as 1848 (Pelichet 1985/2, 34). Pelichet appears to be basing this claim on an official document which, however, we have not been able to find. Pelichet also says that Gonin taught chemistry and physics at secondary school level in Yverdon, before “spending a few months at a faience factory in Bordeaux”.

The article mentioned above, which was published in the Gazette de Lausanne on 22nd March 1879 (and was probably written or co-authored by Jules Michaud), clearly states that Bonnard’s factory “[…] made modest but steady progress until 1859, when it passed into the ownership of Monsieur F. Gonin, a former student of the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, who expanded it and made improvements to its procedures […]”. The city archive of Nyon houses several deeds relating to the factory, which also refer to Gonin (ACN, R 810). On 21st January 1859, for instance, “Frédéric Gonin confirms that he owes François Bonnard the sum of 11,200 francs, which equates to the unpaid portion of an acquisition made by the debtor from the creditor for the sum of 20,000 francs, as attested by the notary’s signature immediately before this deed was signed. […] The debtor undertakes to liquidate his general assets and commits to cede to the creditor the property [what follows is a description of the land with the factory and various other building components on it], which he has just purchased, by special and first mortgage.” In other words, Gonin had just purchased a considerable part of the business (two thirds) from Bonnard. A few weeks later, another deed dated 15th February 1859, records “the acquisition of a residence with two mills on Chemin Sous-Bel-Air […] from Jean Roydor […], by Monsieurs François Bonnard and Frédéric Gonin from Lausanne, in Nyon”. On the same day, the two partners covered the amount by means of a contract of reversion in favour of the cantonal bank.

In our opinion, the partnership between Bonnard and Gonin and the new company name of “Bonnard & Gonin” came into being in 1859, when Gonin became a co-owner of the manufactory. This also helps to explain the unusual transfer-printed design on a coffee cup showing the factory building with the abbreviated mark “B & G” and the date “1859” on its roof (MHPN MH-2003-123).

Let us also cast our minds back to the testimony of the letter writer in the Gazette de Lausanne, who acknowledged the personal merits of François Bonnard and clearly stated that he had run the business from 1845 to 1859 (see above). The catalogue of the above-mentioned exhibition held in 1857 in Bern lists François Bonnard, and him alone, as exhibitor. Gonin’s workshop journal, however, tells us that he had made contact with the company by the autumn of 1858 at the latest.

The archive of the Historical and Porcelain Museum in Nyon Castle houses a workshop journal with Frédéric Gonin’s notes dating from the period between November 1858 and 12th January 1864. The cover has a pre-printed label from the Central School of Arts and Manufactories in Paris for Professor Ferry’s pottery class from the school year of 1841-1842. Gonin had also added the name of the student. The notebook was never actually used as a school exercise book but mainly served as a workshop journal. It contains a series of technical notes, most of which are very brief. In November 1858, Gonin took stock of the factory’s clay supplies and in December he repaired the old pottery kiln. He later built a new kiln. Was this perhaps the “new coal-fired kiln” that he successfully inaugurated in November 1859? Most notes refer to a rather impressive number of clay tests, glazes and paints for refined white earthenware and for brown and yellow cookware (made of French clays from Dieulefit or Bresse). For the production of refined white earthenware he experimented with various mixtures of Cologne clay (probably Vallendar), white Morez clay and sand from Tavannes or Cruseilles.

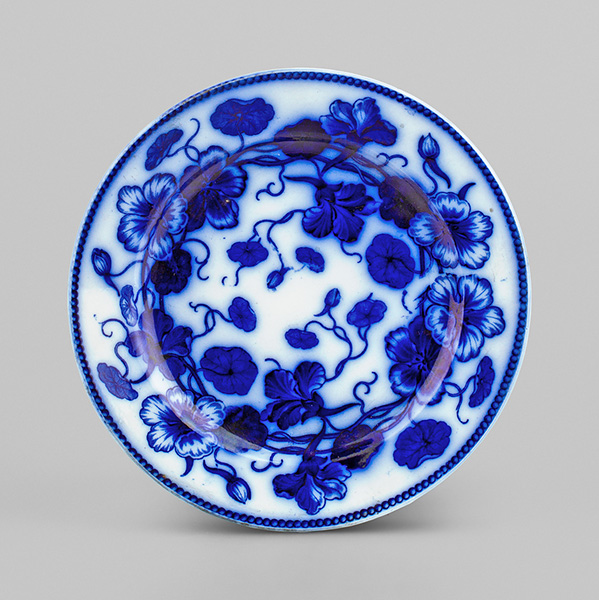

As for the colours he was testing, he mentions a “flowing blue”, which must have been the same colour that was used in English “Flow Blue transfer ware” (MHL AA.MI.994; MHL AA.MI.995).

In a bid to stretch the Cologne clay, he sometimes mixed it with Swiss Cuvaloup clay (or Couvaloup, a type of clay that could be found between Saint-Cergue and La Givrine).

According to the workshop journal, Gonin distinguished between the different clay bodies he was experimenting with by marking them with different symbols, the “NYON” mark or a cross, for instance (MHL AA.MI.992; MHL AA.MI.997). The method appears to have proved successful in Casamène (see MHPN MH-FA-3876-1).

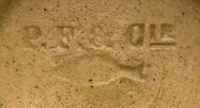

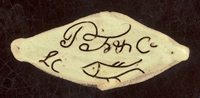

These technical marks, which were not systematically used, sometimes appear together with the transfer-printed mark of the new company: “BONNARD & GONIN” or “POTERIE FINE BONNARD & GONIN”, in an oval frame decorated with two fish, one of which bears the name “NYON”, the other “SUISSE” (MHPN MH-2015-388; MHPN MH-2015-37; MHPN MH-FA-4113).

Gonin’s journal also contains a list of the printing plates that were used for the transfer-printed designs, with information about their motifs: “Flora” – “Musical border” – “Hunting” – “Swiss castles” – “Oak leaves” – “Swiss border” – “Chalets” – “Germany” – “Roses” – “Marbled”. The inventory that was compiled when the equipment was transferred to the new partnership in 1860 mentions an “electroplating machine”. Did Gonin create his own printing plates using the electroplating process?

Some of the motifs mentioned in Gonin’s journal are clearly recognisable on the objects in our inventory, dating from both the “Bonnard & Gonin” period and the early years of the public limited company after 1860:

– A “Chalets” design: MHPN MH-2015-388.

– A “Chalets” design with a border of “Oak leaves”: MHPN MH-FA-10020A and –C; MHPN MH-FA-2885; MHL AA.46.B.17F; MHL AA.46.B.17C; MHL AA.46.B.17D; MHPN MH-FA-10018B.

– A “Chalets” design with a border of “Roses”: MHL AA.MI.994.

– A “Roses” border on its own: MPE 1177A.

– A “Swiss Castles” design with a “Swiss border” (?): MHPN MH-FA-4173; MHPN MH-FA-4113; MHPN MH-2015-443; MHPN MH-2015-445.

– A “Swiss Castles” design with a border of “Roses”: MHPN MH-FA-465; MHPN MH-2015-448; MHL AA.46.B.5; MHL AA.46.B.9.

– A “Swiss Castles” design with a border of “Oak leaves”: MHPN MH-2013-45F; MHPN MH-2013-45E; MHPN MH-2013-45C.

– A “Hunting” design with a border of “Roses”: MHPN MH-FA-4175.

– A “Hunting” design with a border of “Oak leaves”: MHPN MH-2003-122F; MHPN MH-2003-122E; MHPN MH-2003-122B; MHPN MH-2003-122A; MHPN MH-2003-122C; MHPN MH-2003-122D.

CERAMICA CH also includes Swiss landscapes that are not mentioned in Gonin’s journal:

– Swiss landscapes with a border of “Roses”: MHPN MH-2003-123; MHPN MH-2003-124; MHPN MH-FA-465; MHPN MH-2003-125; MHPN MH-2015-338; MHPN MH-2011-22; MHPN MH-2011-23; MHL AA.46.B.7; MHL AA.46.B.8; MHL AA.46.B.10; MHL AA.46.B.6; MM 1203.

– Swiss landscapes with a “Swiss border” (?): MHPN MH-FA-4113; MHPN MH-FA-4111; MHPN MH-FA-3928; MHPN MH-2015-444; MHPN MH-2015-446; MHL AA.MI.992.

– Swiss landscapes with a border of “Oak leaves”: MHPN MH-2013-45C.

It is also worth noting that Gonin continued to use two-colour transfer prints from Casamène (in this example a hunting motif with a musical border in black and blue– MHPN MH-2015-37).

The “NYON” impressed mark continued to be used during the Bonnard & Gonin period, apparently but perhaps not exclusively with a new purpose as a technical mark. As for the transfer-printed mark, we cannot say if it was systematically applied, as coffee cups and saucers were obviously not marked with it. We also noticed that the objects have impressed numerals on the back (see e.g. MHPN MH-2015-37; MHPN MH-FA-4113). It is highly likely that these impressed numbers served to indicate the size of the piece. The numbers we have found (for both the “Bonnard & Gonin” period and for the “Manufacture de poteries S. A.”) were: 2 (plates, diam. 190-194 mm), 3 (plates, diam. 210 mm), 5 (small milk jugs, height 170 mm – teapots, height 158 mm).

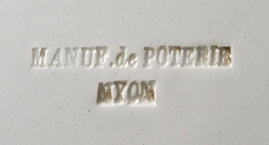

Manufacture de poteries S. A., 1860-1917

Manufacture de poteries S. A., 1860-1917 in CERAMICA CH

The Bonnard & Gonin period was relatively short. The city archive of Nyon houses a deed dated 16th August 1860 with the title “Acquisition by a public limited company of the refined white earthenware factory in Nyon from Frédéric Gonin from Lausanne and François Louis Bonnard from Nyon” (ACN, R 810). It states that Gonin, a civil engineer residing in Nyon, and Bonnard, a merchant from Nyon, the former “owning two thirds”, sold the business to a public limited company which had been set up on 23rd April 1860 (“certified by the notary Berard in Lausanne”). The public limited company was represented by Louis Gonet, a banker in Nyon, with power of attorney granted by Adolphe Burnand, the former director of the Cantonal Bank of Vaud and resident in Lausanne, who is identified in the document as “one of the company directors”. The business was sold for 90,000 Swiss francs. Gonin received 11,200 francs in cash, which allowed him to clear his mortgage with the Robillard heirs, and shares in the new company worth 48,800 francs.

Frédéric Gonin was therefore one of the main shareholders of the company and also served as one of its directors. On 22nd May 1860, one month after its founding, the public limited company signed a loan agreement for 10,000 francs with the Savings Bank of Nyon. It lists Frédéric Gonin and Adolphe Burnand as managers (ACN, R 810). Gonin did, in fact, continue to act as the technical manager, while Burnand (1799-1877), who was actually his father-in-law, probably had the financial oversight of the company (for a brief biography of the first director of the Cantonal Bank, see Revue historique vaudoise, 47, 1939, 111).

On 3rd August 1861, the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 2) acknowledged the upswing in the factory’s fortunes thanks to Gonin and the new company. The estimated value of the annual output was increased to 100,000 Swiss francs, based on the production of “refined white earthenware, white or printed, as well as brown or yellow cookware”. The business employed some 50 people and had the most up-to-date equipment and manufacturing techniques (numerous machines and hydraulic mills, printed designs applied to ceramics using galvanic copper plates). These improvements were introduced by Gonin, “who, for 15 years, worked for and managed the most important pottery factories in France”.

In 1861, Gonin and Burnand donated several objects from their factory to the newly established Industrial Museum of Lausanne to be used for educational purposes (MHL AA.MI.992; MHL AA.MI.994; MHL AA.MI.997).

This included an unpublished design that can be attributed to the manufactory with some degree of certainty (MHL AA.MI.995), as well as a half-finished object (MHL AA.MI.996).

After Bonnard had been bought out, Gonin simply went back to work at the factory, as attested to by his workshop journal. He continued to experiment with various materials, particularly with test firing cookware, and tried to increase the efficiency of the firing process by testing various types of fuel. His notes end in January 1864, two months before he died. On 15th March 1864, L’Estafette (p. 4) published a brief obituary lamenting the premature death of “Monsieur Gonin, the managing director of the pottery factory in Nyon, the running of which was taken over a few years ago and put on a very firm financial footing by this mild-mannered man who was characterised as much by his well-founded knowledge as by his affable nature”.

It goes without saying that the setting up of the public limited company did not have any fundamental consequences for the production techniques, as its main technician still managed it. The “Bonnard & Gonin” mark was obviously dropped but not replaced in any systematic way, as many pieces went unmarked (MHPN MH-2015-443; MHPN MH-2015-444; MHPN MH-2015-445; MHPN MH-2015-446; MHPN MH-2013-45F; MHPN MH-2013-45E; MHPN MH-2013-45C; MHPN MH-FA-10018B).

crushed flint) was introduced, probably by Gonin himself. This production line bore new marks, either stamped (MHPN MH-2015-448) or printed (MHPN MH-2011-22; MHPN MH-2003-122F; MHPN MH-FA-10014; MHPN MH-2003-118). The new impressed marks included the initials “MN” (Manufactory NYON), while the printed marks had a shield with the Nyon coat of arms.

As for the cookware, which must have made up a considerable proportion of the production in Nyon, we have been able to identify only a single example so far: a tureen with manganese glaze (MHPN MH-1997-34); however, with the impressed mark “NYON” and the figure “2”, it is difficult to date.

There are hardly any records from the years immediately following Gonin’s death, neither in the city archive nor in the collections. The 9th issue of the Feuille fédérale suisse dated 29th February 1868 published the catalogue of Swiss exhibitors at the 1867 World Exposition in Paris. Under the heading “Porcelain, refined white earthenware and other luxury ceramics” on page 243 we find only one exhibitor: the Manufacture de poteries de Nyon (Director Versel) with vessels from a “set of cookware”. On 16th February 1867, Le Conteur vaudois (p. 2) published an overview of the exhibitors from the Canton of Vaud in Paris, along with a slightly more detailed critique of the wares put on display by the factory: “brown cookware […] We admired the elegant shape of most of the objects, and the low prices mean that most people can afford to buy them; in this respect we feel that these exhibits merit a mention; the range allows even a tradesman to put objects of sophistication and lightness on his table and thus to treat himself to something akin to luxury”. The museum in Nyon has in its collection “a pricelist of brown cookware – S. A. de la Manufacture de poterie de Nyon” printed on the back of a sheet of writing paper with the letterhead “Manufacture de poteries fines et de terres à cuire – F. Versel, directeur-gérant” printed on the front. We can therefore conclude that the manufactory was run by a man called F. Versel at least from 1867 onwards. The only Versel that we were able to find in the media at the time, was François Versel, a manager and the secretary of the Justice of the Peace in Nyon.

It was in 1869, that a gentleman came on the scene who would put his stamp on the factory for almost the next 50 years: Jules Michaud (1840–1917). The article in the Gazette de Lausanne dated 22nd March 1879, which outlined the history of the company and which we have quoted several times already, tells us that “Monsieur Michaud has run the factory for ten years”. In a document on water rights from September 1880, Jules Michaud is described as the managing director of the “Manufacture de poterie de Nyon, a public limited company set up on 23rd April 1860” (ACN, R 810).

An article about the 1880 National Exhibition of Fine Arts in Lausanne in La Revue on 25th May 1880 (p. 3) said about the manufactory that “[…] it has been producing stoneware objects including jugs, sugar bowls and teapots, all with a yellow glaze but otherwise undecorated, for approximately two years. It now manufactures more and better-quality products [the ceramics produced on behalf of the Pflüger brothers, see below]”. The term “stoneware” here is clearly incorrect. According to the article in the Gazette de Lausanne dated 22nd March 1879, Jules Michaud began to develop a range of art pottery “around September 1878, having worked tirelessly and continuously, and having experienced unceasing setbacks and carried out innumerable experiments”. This new production line was launched in collaboration with the company Pflüger Frères et Cie, the owners of the Bazar vaudois in Lausanne. In this particular project, Pflüger Frères et Cie were in charge of the designs.

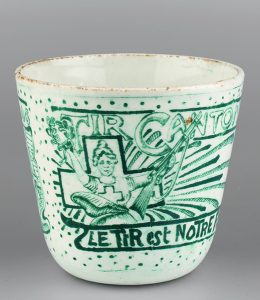

The collaboration with Pflüger Frères & Cie, 1878–1883

Pflüger Frères & Cie, 1878–1883 in CERAMICA CH

In an article entitled “La porcelaine et la poterie à Nyon [Porcelain and pottery in Nyon]”, published in the Journal de Nyon on 6th and 11th April 1893, Jules Michaud described what had occurred: “The manufactory embarked on a new venture by developing a novel branch of art pottery with slip decoration for and in collaboration with the Monsieurs Pflüger & Cie […] a series of magnificent pieces were made, some of which were even sold abroad, but sales were limited due to the very high cost price, and production soon ceased”.

The Bazar vaudois was a true Lausanne institution founded in Chemin-Neuf by Louis Pflüger the elder (who died in 1858) and Benjamin Corbaz (1786-1847) in 1831. The company aimed to market all products of craftsmanship and industry in the Vaud region using a novel business model: the manufacturers gave their products to the Bazar to sell, and the company charged a warehouse fee and a commission on the sales price. After a few years Corbaz left the company to focus on his original profession as a book seller and publisher. The Bazar’s range of products was gradually broadened by adding wares from other parts of Switzerland and later from abroad. In 1856, the shop, which had expanded considerably, was moved to a bigger premises on Place Saint-François (J. Z. 1871; Monnet 1881; Bridel 1919; Bridel 1931).

When Louis Pflüger died, his son Philippe (1820–1895) took over the company in partnership with Charles Burnand from Moudon. From 1877 onwards, the business was apparently called “Pflüger Frères et Cie” (Monnet 1881). This was when two of Philippe’s sons, Charles (1849–1927) and Marcus (1851–1916), joined the company. Their father was obviously preparing for his succession. The handover was finalised with the founding of a new limited partnership in February 1882, with Charles and Marcus being “partners with unlimited liability”, while Philippe Pflüger and Charles Burnand were limited partners (Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce [SOGC], Vol. 1, 1883, p. 106).

A third son of Philippe Pflüger, Louis (1847–1893), was not mentioned in the context of the Bazar; however, it is known that he played a role in his brothers’ ceramic venture. Although he was interested in the arts, painting in particular, his parents initially failed to include him in the family business. In the period between 1870 and 1872, he trained with Joseph-Eugène Gilbault, a flower painter from France, in Lausanne, before travelling to Paris, where he continued his training with the landscape artist Pierre Dupuis and the flower painter Victor Leclaire. Back in Lausanne he spent some time painting in oils, but mainly he was a watercolourist with a distinct preference for floral themes. He participated in several exhibitions around Switzerland and also in Brussels (Vuillermet 1908).

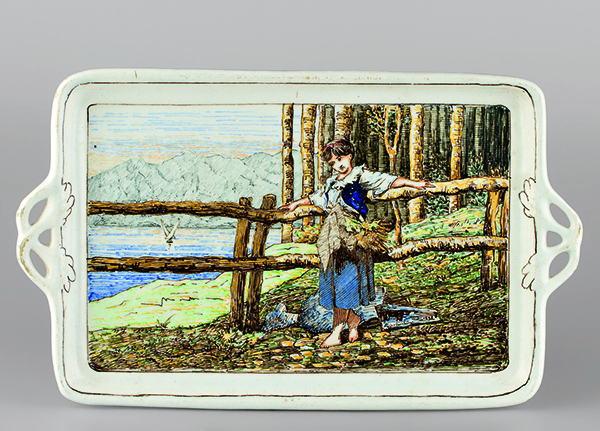

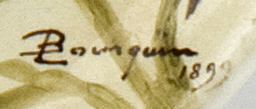

Writing about Louis Pflüger in the Lexikon der Schweizer Künstler [Encyclopaedia of Swiss Artists], Charles Vuillermet, drawing on information provided by the artist’s family, described him as a “painter and ceramicist”. He went on to say that Louis had “for a few years devoted his time to pottery making. Provided with excellent decorators by the Geneva School of Art, he set up an industry that had not previously existed in our country: the manufacture of art pottery, which became known under the name ‘Nyon’. The pottery was adorned with applied decoration and moulded decoration in relief as well as in-glaze painted decoration […] Pflüger ran the factory in Nyon from March 1878 until 27th January 1882” (Vuillermet 1908). Describing Louis Pflüger as a ceramicist is quite an exaggeration, even though he may have become somewhat familiar with the medium over time. As for the myth that he ran the factory, it was obviously a figment of the family’s imagination. We will come back to this misinterpretation later.

The Pflüger brothers were not content with marketing the products of Vaud craftsmanship and industry but decided in the spring of 1878 to launch their own product line under the leadership of Louis. Because they chose the field of pottery to branch out into, they decided to do this in synergy with the factory in Nyon, which was the only business in the region that had the basic wherewithal to source and provide the suitable raw materials and the technical infrastructure required. Louis Pflüger, the artist among the siblings, would develop the aesthetic for the products and a studio was set up specifically for the purpose within the factory (La Revue dated 25th May 1880, p. 3), where the designs were painted and moulded onto the vessels prepared by the company’s throwers and modellers. Louis Pflüger appears to have headed up a small group of decorators, painters and modellers, who were probably recruited from the Geneva School of Engineering (the School of Arts and Crafts was only founded in 1903)

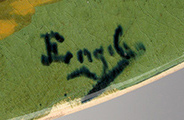

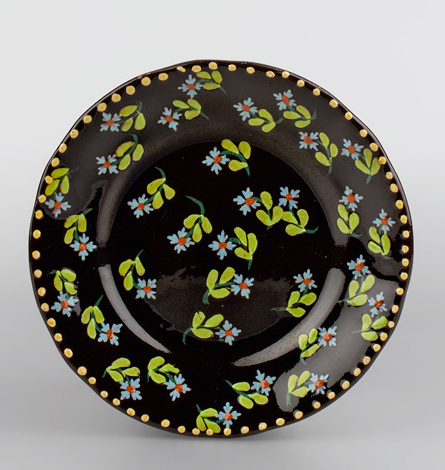

Many of the designs were signed, often simply with initials. Only two names were written in full: Junod, who seems to have come from Neuchâtel, and Engel (MHPN MH-FA-2137; MHPN MH-2013-42).

a coat of coloured slip (usually brown-black) and then coated in a colourless glaze (e.g. MHPN MH-FA-3127; MHPN MH-FA-2686; MHPN MH-1998-307; MHPN MH-2011-29). Another category of objects, which caused quite a stir at the time, were decorated using the same technique, but with floral and animal motifs moulded in high or low relief being applied before the vessels were painted and glazed (e.g. MHPN MH-2011-27; MHPN MH-2000-108; MHPN MH-2011-31). The first group included motifs that showed a certain degree of historicist eclecticism (MHPN MH-FA-3127; MHPN MH-FA-2686; MHPN MH-1998-307; MHPN MH-1998-308; MHPN MH-2015-49; MHPN MH-2013-39). The Swiss National Museum in Zurich has in its collection a brown jug with motifs that emulate the “Old Thun” style of the contemporaneous factories in Steffisburg and Heimberg (SNM LM-80590). The object is representative of the early period of production as attested to by the date engraved on the tin lid: “St. 29 October 1878”. The fact that this type of pottery had become so popular with consumers thanks to international tourism, which was beginning to flourish at the time, would definitely have had an influence on the Pflüger brothers’ decision to embark on the adventure in the first place. It was not long, however, before they adopted a less folkloristic style.

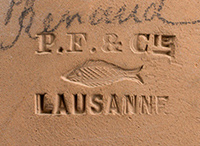

The clay used in these creations was either the usual red or a fine beige earthenware (perhaps this was the yellowish “stoneware” mentioned above?), or else a refined white earthenware. The products were all clearly marked with the letters “PF & Cie” and a fish.

Some marks were painted (MHPN MH-FA-4215; MHPN MH-2015-44), others were incised (MHPN MH-FA-4433A; MHPN MH-FA-4220) and yet others were fashioned as a white slipped cartouche in the style that is found on “Old Thun” pottery (MHPN MH-2015-40). Impressed marks were also used (MHPN MH-2009-1).

The mark was officially registered in November 1880 (Bundesanzeiger, 1880, Volume IV, Book 48, 64) under the number 197. The official publication shows the impressed mark. The same drawing was used in an advertisement by Pflüger announcing the opening of a second showroom in the “chalet”, an annexe to the Grand Bazar, which had been erected opposite the Flon railway station not long before and which was set up specifically as a salesroom for their “in-house” pottery (L’Estafette, 29th July 1880, p. 3, and 8th December 1880, p. 1). The advertisement contained a warning to customers: “Because Swiss and French pottery is sold as purportedly originating from the factory in Nyon on a daily basis, please check for the mark shown below.” From spring 1879 onwards, the Pflüger brothers regularly placed notices in the Lausanne press advertising their “art pottery from the manufactory in Nyon”.

Because of their colourful and sometimes even spectacular style, the Pflüger brothers’ creations attracted the attention of the critics and eclipsed all the other products that were being made in Nyon at the time – and quite rightly. The catalogue of the 1883 National Exhibition in Zurich lists the factory with the same exhibitor number as Pflüger Frères and even seems to be something like a “sub exhibitor”. Pflüger Frères et Cie were awarded a certificate “for their artful refined white earthenware with applied decoration and for their role in setting up this industry in Switzerland” (Messerli 1991, 17-18 and footnote 124; Le Nouvelliste vaudois, 4th April 1883, p. 3).

The assessment made by the jury appears slightly exaggerated. The Pflügers’ well-known applied decorations were not their own creations but had, rather, been inspired by the contemporary – though more accomplished – designs of Eugène Hécler’s workshop which was in operation in Ferney-Voltaire between 1881 and 1907 (Clément 2000, 87-91; see also MAHN AA 1343; MAHN AA 3351; MAHN AA 1342; MAHN AA 1344). Objects of a similar style were also made by Picolas & Degrange in Carouge (Dumaret 2006, Fig. 91) and by Alexandre Schwarz at the Poterie des Délices in Geneva (registered in the SOGC on 13th January 1883 [Vol. 1, 1883, 42] – The Musée Ariana has in its collection a black-brown vase with a polychrome bouquet of flowers in applied decoration, MAG AR 07896). Both Picolas & Degrange and Alexandre Schwarz exhibited the same type of pottery in the ceramics section of the Zurich National Exhibition in 1883 next to the Pflügers’ creations (Journal de Genève, 11th May 1883, 1)..

The press in the Canton of Vaud welcomed the endeavours of the Pflüger brothers in Nyon with much enthusiasm. They were quite emphatically feted as the great innovators of the Nyon pottery-making tradition and as the founders of a new branch of industry which looked very promising for the Canton of Vaud’s economic development (see, for instance, a report on the National Arts Exhibition in L’Estafette dated 26th May 1880, p. 5). This even led to misinterpretations: we have come across several accounts of how the Pflüger brothers had bought or even founded the factory in Nyon. Even though the new art pottery would never have seen the light of day without their initiative – and the financial investments they probably agreed to make – we must not forget that the Pflüger brothers would never have been capable of creating a single ceramic object without the technical expertise of Jules Michaud and his staff.

Their collaboration lasted for four years. According to family lore, Louis gave up “running the factory in Nyon” on 27th January 1882 (Vuillermet 1908). A notice placed in the Lausanne by Pflüger Frères press in December 1883 (e.g. in the Gazette de Lausanne dated 1st December, p. 4), announced that “our workshops were moved from Nyon to Lausanne on 1st September 1883”. The notice also advertised the following: “sale of modelling clay and firing of finished pieces”. In our opinion the workshop that had been moved to Lausanne must have been a decorating shop, fitted, at most, with a muffle kiln which was used solely for fusing decorations. Throughout 1884, a series of advertisements appeared for “painting courses and private lessons with Monsieur Louis Pflüger, specialising in flower painting on silk fabric, porcelain and refined white earthenware and watercolour painting”. The studio was located at 17 Avenue de Villamont. Another advertisement the following year announced that “Pflüger Frères & Cie. will be firing porcelain on the 1st and on the 15th of every month and will subsequently dispatch the fired pieces. The company also offers a complete range of porcelain-painting paraphernalia for sale”. The Pflügers had clearly discovered a new gap in the market offering services for independent and amateur porcelain painters. The company’s advertisements no longer mention art pottery. In 1886, the “pottery factory at the Flon train station” offered a clay modelling course “for ladies” (L’Estafette dated 6th January 1886, 2); a few months later, the company was advertising an exhibition of “artistic and industrial products that might interest people from abroad” which was to be held at the same place, the “Chalet du Flon”, a former Mecca for their famous pottery (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 27th May 1886, 1).

In 1888, the Pflüger brothers staged a pottery exhibition at the Athénée centre in Lausanne of “hundreds” of decorated faience and porcelain objects made by approximately forty exhibitors, some of which must have been their customers, particularly female customers, as it was apparently “mainly the ladies who excel in this delicate and charming art form” (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 10th September 1888, 4). Products from the “factory of the Monsieurs Pflüger” were also on display.

On 16th September, L’Estafette (p. 5) published an article about “three pretty dishes” exhibited by Louis Pflüger. According to the piece, they were “decorated in a special manner; the work is more reminiscent of oil painting than of pottery”. The description is a perfect match for the only object known to us that bears a Lausanne Pflüger mark (MHPN MH-2000-174).

If Louis Pflüger did, in fact, produce pottery in Lausanne, he probably restricted himself to decorating wall plates or dishes, which were delivered in the biscuit-fired state by one pottery or another; the final firing could then be carried out in his muffle kiln. We do not believe that the Lausanne workshop would have been capable of creating objects as complex as those previously produced in Nyon.

The everyday production

Following the closure of the Pflüger brothers’ decorating shop in Nyon, the factory seems to have continued to produce pottery in the same naturalistic style for some time, as shown by two pieces from 1883 and 1884/1885 respectively (MHPN MH-2015-42; MHPN MH-2015-51).

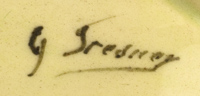

These later objects simply carried a painted or incised “Nyon” mark; several bore the signature of Gaston Fresnoy, a ceramicist from the Département Côte-d’Or (MHPN MH-2015-42; MHPN MH-2015-51; MHPN MH-1999-22; MHPN MH-FA-4064). The communal archive in Nyon has an 1899 savings book in his name, which was probably provided by the factory (ACN, R 810).

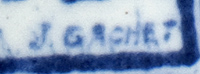

A signed vase attests to another collaboration, this time with Jules Gachet, a painter from Nyon (MHPN MH-2015-39).

The manufactory’s everyday production is not very well documented. According to the catalogue of the National Exhibition in Bern in 1883, the factory exhibited “white crockery” (refined white earthenware) and brown cookware. At the Vaud regional exhibition in Vevey in 1894, the factory in Nyon appears to have taken up less space that the potteries in Renens, “though their products were pleasing to the eye. Some of them bore pretty designs painted in high-temperature colours. Particularly worth noting is a dish with a rural motif in applied decoration” (L’Estafette, 7th August 1894, 1). The manufactory was awarded a gold medal and a certificate (L’Estafette dated 7th August 1894, 7).

On 2nd October 1894, the Gazette de Lausanne (p. 1) again wrote about the Pflüger brothers’ production in a rather detailed report: “Under the astute leadership of the Monsieurs Pflüger, whose workshops were moved from Nyon to Lausanne a few years ago, the production of faience objects and art pottery with applied decoration has taken a new and bright path in its evolution; the exhibition, however, only includes their current production lines: […] the blue designs on these pieces did not come from the brush of an artist, but rather from a simple cutout cardboard stamp, which was loaded with paint and then skilfully applied to the body of the vessel like a seal. […] some of the models on display are artful faience pieces decorated with a brush; this production line, however, had to be discontinued because it was no longer profitable”.