Andreas Heege, Andreas Kistler 2019

History of research

The earliest mention in the literature of a pottery tradition in Berneck dates from 1921. At that time, Fernand Schwab was keenly interested in the formation and development of the pottery tradition in Heimberg and its impact on other areas, including Berneck (Schwab 1921, 60). In 1924, Daniel Baud-Bovy (1870–1958), President of the Eidgenössische Kunstkommission [Federal Arts Commission] (1916–1938) wrote a book entitled “Peasant Art in Switzerland”, which also contained a chapter on Swiss pottery production. In this context he mentioned a store sign from a pottery workshop in Berneck, which at the time was already part of the collections of the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum St. Gallen (Historical and Folklore Museum) (Baud-Bovy 1924, 61 and Fig. 369. German translation: Baud-Bovy 1926, 77 and Fig. 311; HVMSG 9528).

From the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

It shows a potter working at his wheel. However, there is no mention of the products from the Berneck workshops in Baud-Bovy’s book.

Another reference to a pottery tradition in Berneck, this time from 1947, came from the pen of Karl Frei, Deputy Director of the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum [Swiss National Museum] who at the time was one of the most renowned experts on Swiss earthenware (Frei 1947, 31). In a volume to accompany the exhibition on “Swiss Pottery from prehistory to the present day” curated by the Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich (Museum of Applied Arts in Zurich), Frei wrote about “black-coated pottery in the Heimberg style”, which was being sold by “door-to-door salesmen in the Appenzell region and Vorarlberg, in the Grisons and as far afield as Bavaria” (probably quoted by Creux 1970, 125, unsourced). It is not clear where this information came from, nor are there any pictures of the pottery, probably because the Swiss National Museum itself did not have any significant pottery collections, but only plaster of Paris moulds and slip-trailers from the then liquidated Berneck workshop of G. Federer (SNM LM-68232 to LM-68240, slip-trailers; LM-68241 to LM-68245, utensils; LM-68246 to LM-68315, plaster of Paris moulds and objects that came from them). The most significant object from Berneck in the Zurich collection is a matchstick holder in the shape of a bear holding a shield of the Canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden. It bears the signature “I. O. K.” and can therefore be attributed to the Berneck workshop of Josef Othmar Kurer (Schnyder 1998, 113 Cat. 178; SNM LM-13187). The matchstick holder shows that Berneck workshops also created pottery with speckled decoration (i.e. with iron manganese particles in the slip).

Matchstick holder in the shape of a bear from the Swiss National Museum

Robert Gschwend (Gschwend 1948) and Leo Broder (Broder 1955; Broder 1975) were the first researchers to publish studies of any significance on Berneck products, although they were not substantiated by a sufficient number of archival sources either. They nevertheless formed the basis, along with an analysis of the sources from the municipal archive carried out by former mayor Jakob Schegg, for a pottery exhibition held in the Ortsmuseum Berneck (OMB) [Berneck local museum] in 2006, which prompted the publication, a year later, of a more richly illustrated study on the history of Berneck pottery by Margrit Wellinger-Moser (Wellinger-Moser 2007).

The history of pottery production in Berneck definitely dates back to the late 17th or mid-18th century, as shown by a signed but undated Baroque tiled stove made by stove-fitter “Johan Ulerich in der Mur, Haffner In Berneg” in the “Salis House” in Maienfeld (Broder 1955, Fig. p. 45. On the stove see Poeschel 1937, 30, Fig. 28).

Kachelofen in Maienfeld

It is decorated with polychrome underglaze brushwork and has allegorical depictions of the Virtues together with fitting quotes from the Old and New Testaments on its upper structure. This is contrasted on the lower part by the Vices. From a stylistic point of view, the stove has close parallels among Steckborn products. Previously stored in the attic of the house, the stove was newly fitted by the Zug stove-fitters Keiser in 1933 and extended by the addition of a seat on one side. The first mention of a certain “Ulrich Indermauer, potter” comes from a Bernang (former name of Berneck) court record dating from 1685 (Einiges über Töpferei, anon., Unser Rheintal 5, 1948, 81–82). The next reference to Berneck pottery dates from the 19th century. In 1828, the records state that there were four workshops in Berneck, while between 1830 and 1850 the neighbouring municipalities of Au, Balgach and Lüchingen near Altstätten had three workshops each, two existed in Altstätten itself and one each in Rebstein and Marbach. Records from 1836 mention a dispute about the exportation of clay to Austria, which shows that there must have been some sort of rivalry (perhaps between local potters and their counterparts in Vorarlberg?). Potters by the name of Indermauer and Lang successfully lobbied the local council and their restrictive attitude prevailed (Boesch 1968). According to master potter Ritz sen., who passed away in 1931, there were 21 pottery workshops in Berneck around 1870 and 19 across the river Rhine in Lustenau, Vorarlberg. Records for 1872 attest to 18 master potters in Berneck (Boesch 1968, 180) and in 1878 there were at least 17 potters from the following families:

Federer, Grüninger, Hasler, Hongler, Jüstrich, Kurer, Lang, Mätzler, Ritz, Schädeli, Schuppli, Seiz, Thurnherr und Zangger.

The names were taken from a subscribers’ list to the “History of the municipality of Bernang” published in 1879 by the Catholic parish priest of Berneck, Franz Xaver Kern (Kern 1879). By 1899 the number of potters or potters’ workshops had decreased to twelve, by 1905 to nine, by 1913 to seven, by 1920 to six, by 1931/1937 to three and by 1948/1955 to one, which had been established in 1902 by master potter Hans Ehrat. It would subsequently become the Hanselmann pottery, which was later taken over by Hans Plattner and is now owned by Fred Braun (Gschwend 1948; Broder 1955; Boesch 1968, 209; Wellinger-Moser 2007, 251–255).

In 2016, the history of Berneck pottery was examined in detail for the first time from an archaeological perspective and from the point of view of cultural history (Heege 2016, 28-36). In 2017, Andreas Kistler added his own research results (Heege/Kistler 2017, 369-373) and in 2019, a basic typological differentiation was made between Berneck pottery and the products from the Lötscher pottery in St. Antönien (Heege 2019); at the same time, the entire pottery collection from the Raetian Museum as subjected to a comparative study. The following paragraphs present the results obtained from these studies.

Berneck SG and Heimberg BE – “Heimberg-type pottery”: a conundrum

In 1921, 1955 and 1975, the typological links between Berneck and Heimberg were explained by “Heimberg women” marrying into Berneck pottery families, even though neither Fernand Schwab, nor Leo Broder or Hermann Buchs from Thun (according to Gresky 1969, 41) provided any genealogical proof. Fernand Schwab wrote: “As little as 20 years ago, there were similar ties between Heimberg and Bernegg: many a young Bernegg potter who learnt his trade in Heimberg or served there as a journeyman brought home a potter’s daughter from there to settle down as a master at home” (Schwab 1921, 60). Because it can be shown that as early as 1836 it was usually the women who carried out the painting in Heimberg (as attested to by Alexandre Brongniart, the director of the main porcelain manufactory in Sèvres, France, who visited Heimberg on his travels around Switzerland: Brongniart 1854, vol. 2, 14–15), this could indeed be seen as one explanation for the close similarities in the decorative canon that existed from around 1800/1820 between Heimberg and Berneck. Unfortunately, this theory must be refuted.

When Jakob Schegg studied church records in search of the places of origin listed for the wives of the known potters in 19th century Berneck (I would like to thank Jakob Schegg, former mayor, for the detailed and highly informative discussion on his as yet unpublished research results), he did not find any marital links between Heimberg and Berneck for the very important early part, or for the second half of the 19th century (mentioned for the first time by Wellinger-Moser 2007, 254). The church records of Steffisburg do, however, show one interesting link for an originally Catholic potter from Berneck named Leondus Federer, son of Joseph Federer, who was said to have settled in Heimberg sometime prior to 1819, but later returned to Berneck (Steffisburg Church Register 17, 163 no. 23. Five of his children died in 1822, 1825 and 1828, as also recorded in the Steffisburg Church Register: 22,99; 22,111; 23,9 and 10). He married Elisabeth Rubli, a widow from Dachsen in the Canton of Zurich on 26th November 1819 in Münsingen. Her previous marriage had been to Caspar Joder from Steffisburg (not a potter!) in 1816. He had died on 18th March 1818 (Steffisburg Church Register 17, 141 and 22, 84 no. 27). When a son of Leondus Federer, who had been born in 1824, was christened in Steffisburg, Franz Joseph Kurer, a potter from Berneck acted as his godfather (Steffisburg Church Register 10, 214).

If we accept, therefore, that it was not the female pottery painters who were responsible for the typological and stylistic transfer of knowledge between Heimberg and Berneck, the only other possible explanation, ultimately, is journeymen moving between the two areas. Based on work carried out by Andreas Kistler, we now know that between Johann Michael Kurer, the first journeyman known to have been in the region of Heimberg in 1823, and Joseph Anton Ritz, the last recorded journeyman in 1905, the registry of foreign citizens in Bern recorded a further six journeymen from Altstätten, five from Au, five from Balgach, eleven from Berneck and one from Marbach. The fact that various journeymen from Berneck worked for one or two-year periods in the region of Heimberg-Steffisburg, goes some way towards explaining how skills and decorative motifs were transferred between the regions within a relatively short period of time. And it also means that it is quite possibly very difficult to distinguish between pottery from the Berneck region and that from the Heimberg-Steffisburg area. That is why the descriptions in the database always contain the term “Heimberg-type pottery”. As for objects from the antiques trade the question of provenance will ultimately have to remain unanswered, although we can assume that the majority of simple utilitarian ware from the Grisons was probably produced in the Berneck region. We must not forget, however, that we have no concept of what the pottery produced in neighbouring Lustenau in Vorarlberg would have looked like.

Pottery from Berneck

The earliest use of coats of dark slip in Berneck was dated by Leo Broder to a period during which they had not even begun to be used in Heimberg. This is not plausible, as Berneck was definitely not the primary centre of this stylistic development. Broder’s theory was based on a plate bearing the date 1772, although it is almost impossible to think that its drapery pattern could have dated from earlier than the 1830s (Broder 1955, Fig. p. 51. Broder 1975, Fig. p. 3). On the other hand, the plate also bears the placename “Bernang” and thus may indeed be an important example of the products that were made there in the first third of the 19th century (Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum St. Gallen, HVMSG 8347).

Pottery from the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

Even more important in this context is a small costrel which Hessian journeyman Konrad Pistor brought home from Berneck, his last place of employment (from November 1848 to May 1849); on his travels he had also visited Heimberg, as had his grandfather before him. It bears his name and the date 1849 on the front as well as an incised inscription running around the front and back, which is unusual for Heimberg ware, both with regard to its technical execution and in terms of its content. A shield surrounded by drapery shows a bear passant toward dexter, which closely resembles the Bernese coat of arms (Gresky 1969, 39 Fig. 8. Broder 1975, 7, picture at bottom left). The bear, however, is wearing a collar, as is typical of Bäriswil bear depictions, and therefore obviously does not represent the coat of arms of the Canton of Bern, but probably acts, rather, as a canting arms for both Berneck and Bäriswil. A shaving basin with a coat of black slip and bearing the date 1840 that belonged to master bricklayer Johannes Kurer from Berneck shows a very similar decoration (HVMSG 7278a).

Pottery from the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

A large very flat bowl with bevelled rim, a coat of red slip and white slip-trailing as well as a decorative frieze with incised floral motifs bears the motto “Long live the potters in Bernneg” (HVMSG 9764), leaving no doubt about its place of production. Another bowl with identical decoration on the rim bearing the motto “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” is kept in the collection of the SMT (inv. 568).

Pottery from the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

When looking at “Heimberg-type pottery” in the collections of the museums at Berneck, Heiden, St. Gallen, Frauenfeld and Triesenberg, it becomes obvious that numerous pieces have decorative motifs that are not usually found on pottery from Heimberg. They include two flat bowls (form SR 17), one with four figures (possibly a christening party?), probably not in Bernese costume (Museum in Heiden, no inv.), the other with a house that is not typically Bernese in style (RMC H1970.185), a single-handled jar (form HTR 12) dated 1849 (HVMSG 2010-01), a coffee pot of unusual shape dated 1827 (Walser Museum Triesenberg, no inv.) and a flat bowl SR 17 dated 1852 (HVMSG 9129), to which numerous other examples can be added (HVMSG 8656 and 8657, Museum Heiden no inv., RMC H1971.914, OMB 2010.1494).

Pottery from the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

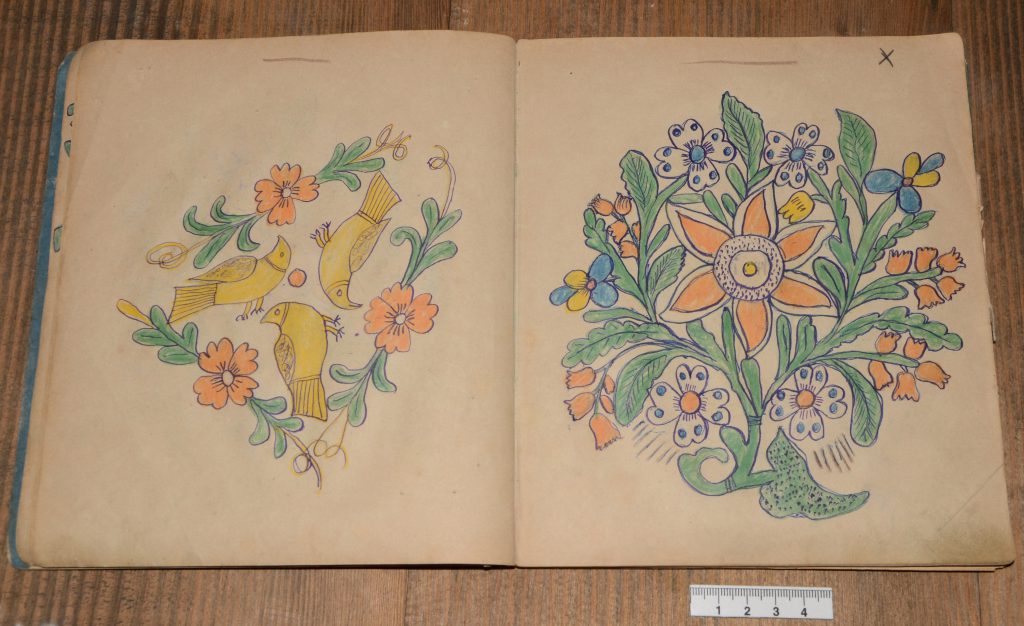

Some of the vessels’ decorative elements correspond to motifs found in a pattern book that belonged to a pottery paintress from Berneck (Ortsmuseum Berneck [Berneck local museum], OMB no inv.; e.g. OMB 2010.1567, 2009.1123).

Pattern book from the Ortsmuseum Berneck

The same variability becomes apparent when comparing objects like tureens from the Rätisches Museum Chur or the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen.

Pottery from the Rätisches Museum in Chur

The museum inventory attributes all these vessels wrongly to St. Antönien workshops, probably because the first piece (RMC H1970.238.) was acquired in 1907 from Andreas Lötscher the younger, the last potter to have worked at St. Antönien. The majority of the objects, however, (RMC H1973.831, H1973.836, H1973.841, H1973.956, H1973.841, H1973.956, H1973.958) originated from the collection of Margrith Schreiber von Albertini in Thusis and were bought on the antiques market in 1973 as “St. Antönier-Geschirr [St. Antönien ware]”. A study on the pottery from the Lötscher workshop in St. Antönien (Heege 2019) has since proved beyond doubt that none of these tureens were actually produced there. Another piece from the same group of tureens, on the other hand, was acquired together with a matching single-handled jar from a private individual in Rodels (RMC Inv. H1984.1, H1984.2). Alongside various other examples kept in Grisons museums, they show just how widespread this type of pottery was in the Canton of Graubünden.

Pottery from the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen

By contrast, the museum inventory of the Historisches und Völkerkundemuseum in St. Gallen attributes its large number of tureens, of which we can only show a small selection here, to Berneck without any further discussion, but this is probably just because they are now located in the Canton of St. Gallen.

“Heimberg-type pottery” from the Canton of Bern.

On the other hand, if we compare the painted motifs with examples that are still in use in Oberdiessbach in the Emmental valley or with pieces from collections in Burgdorf or Mürren (BuumeHus in Oberdiessbach, no inv.; SMB IV-918; Fahrländer-Müller Collection K82), which were quite possibly produced in the Heimberg region, the similarities are so striking, that it can only fill us with surprise, given the current state of research and provided we do not assume that Heimberg products were traded to Graubünden or Liechtenstein some 200 km away (see also finds from Bernese excavations: Heege 2010b, 89 Abb. 77). The only plausible explanation is to assume that at least one other important centre of production for “Heimberg-type pottery” was located in the St. Gallen Rhine Valley besides the possible places of production at Kandern in the southern Black Forest area (Eisele 1929; Eisele 1937; Gebhardt-Vlachos 1974; Schüly 2002) and Steckborn in the Canton of Thurgau (Heege 2016, 64-66), and that this centre’s area of distribution stretched as far as the Cantons of Schaffhausen (Heege 2010, 67–69), Thurgau, Zurich (Hoek/Illi/Langenegger et al. 1995, Pl. 9,181–182; Pl. 10,184.186; Frascoli 2004, Pl. 13,75, c. 1800?; Pl. 17,124, terminus post quem 1905), St. Gallen, Appenzell Innerrhoden and Ausserrhoden (Obrecht/Reding/Weishaupt 2005, 102, Cat. 179) and Graubünden (cf. RMC), as well as the Principality of Liechtenstein (Heege 2016) and the Vorarlberg region of Austria (Heege 2016, 62-64). Moreover, finds of pottery with similar decorations, for example from Schwäbisch Hall (Gross 1994), as well as black-coated pottery from Middle Franconia (Bauer 1971; Bauer 1979; Bauer/Wiegel 2004) may point to the existence of additional places of production in the Württemberg region which could also have supplied the eastern areas of Switzerland.

Pottery in the style of “Thun majolica” from Berneck

Very little evidence has to date come to light for the late phase of Berneck pottery production, i.e. for the late 19th century. In 1883, potter Richard Grüninger from Berneck presented a “collection of ceramic wares” at the inaugural Swiss National Exhibition in Zurich (Messerli Bolliger 1991, 17). According to the inventory register of the Musée d’art et d’histoire de Neuchâtel [Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel] (MAHN), three of Grüninger’s Rösti dishes with bevelled rims were added to the collection in 1886. While the vessel shapes are typical of the German-speaking part of Switzerland, the decorations on the coats of beige or red slip are quite unusual and not in keeping with standard Heimberg conventions: besides black slip-trailing there is also white and polychrome stencilled decoration (Blaettler/Ducret/Schnyder 2013, Pl. 79,7–9).

Pottery created by Richard Grüninger from Berneck, 1883, Musée d’art et d’histoire de Neuchâtel (MAHN)

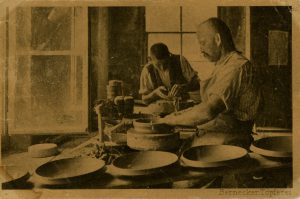

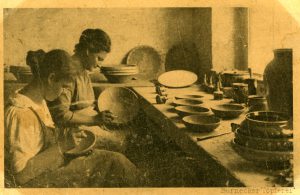

In the 1880s, various efforts were made, by the “Kaufmännisches Direktorium St. Gallen” (Association of St. Gallen Merchants) among others, to improve the economic circumstances of the potters of Berneck, which were obviously rather difficult at the time. Their lack of success was attributed to the absence of “elegant forms and [to] a lack of appealing painted decoration”. In an attempt to remedy the situation, drawing classes were set up (run by teacher Nüesch) and a touring exhibition was staged over a two-week period by the St. Galler Industrie- und Gewerbemuseum (Industry and Trade Museum St. Gallen) which showed the potters what “perfectly shaped and painted” ceramic wares could look like (Boesch 1968, 180, unsourced). Unfortunately it is not known what exactly was shown to the potters at the time. Based on a number of photographs that have survived

and products that are still kept at the Ortsmuseum Berneck, however, it appears that they were encouraged to produce pottery in the style or with the flower and Edelweiss motifs of “Thun majolica” (Museum Heiden, no. inv., OMB inv. 2010.1579, 2010.1580, 2010.1581, gifted by the Trudi Hanselmann Pottery). The Stegkanne (spouted pitcher) shown in the photograph still survives (OMB, no inv.) as does a variant version of a plate with the coat of arms of all the cantons (OMB 2010.1535). The picture also shows shallow bowls with bevelled rims and vessels with horizontal bands typical of the period, as well as vessels shaped like “Heimberg” tureens.

Pottery in the style of Thun majolica from Berneck (collection of the Ortsmuseum Berneck)

The measures, however, do not appear to have been particularly successful. “The Vorarlberg carters, who had in the past transported whole cartloads of cups and bowls home to their little country, failed to appear” (Boesch 1968, 209).

The Ortsmuseum Berneck also holds the remains of a twelve-part series of postcards, probably from 1923 (on the occasion of the Rhine valley trade show), from one of the last working potteries in Berneck. They are a rare testimonial to a craft that was slowly dying out at the time. The complete series can be found here.

Summary

The results from the study strongly suggest that the pottery coated in black, white, red or beige/orange slip found in Liechtenstein, Vorarlberg and Graubünden was imported from one or more places of production which have not yet been identified, but that the majority of these wares were probably made in Berneck, though in the absence of scientific analyses the appearance of “true” Heimberg pieces ultimately cannot be definitely excluded. To ascertain which of the “Heimberg-type” vessel shapes and decorative motifs were actually made in Berneck would probably require excavations or at least scientific analyses. So far, there has been a lack of both. It would be most desirable for an in-depth study on the pottery history of the Berneck region to be undertaken. Any objects in the database that are today in the Canton of Graubünden and whose place of manufacture is said to be “Berneck”, should be viewed as originating from the “Berneck region” and we cannot discount the possibility that this may have included parts of Vorarlberg; moreover, it is possible that evidence will come to light at some point in the future to show that identical wares were also produced in other areas of the Canton of St. Gallen. It is not possible for the time being to distinguish between these wares and the “Heimberg-type” pottery that was produced in the Canton of Zurich, for example at the Hanhart Factory in Winterthur.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References

Baud-Bovy 1924

Daniel Baud-Bovy, Peasant Art in Switzerland, London 1924.

Baud-Bovy 1926

Daniel Baud-Bovy, Bauernkunst in der Schweiz, Zürich/Leipzig/Berlin 1926.

Bauer 1971

Ingolf Bauer, Treuchtlinger Geschirr (Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 45), München 1971.

Bauer 1979

Ingolf Bauer, Hafnergeschirr im Ries, in: Rieser Kulturtage-Eine Landschaft stellt sich vor. Dokumentation 2, 1979, 273-296.

Bauer/Wiegel 2004

Ingolf Bauer/Bert Wiegel, Hafnergeschirr aus Franken (Kataloge des Bayerischen Nationalmuseums München 15,2), München 2004.

Blaettler/Ducret/Schnyder 2013

Roland Blaettler/Peter Ducret/Rudolf Schnyder, CERAMICA CH I: Neuchâtel (Inventaire national de la céramique dans les collections publiques suisses, 1500-1950), Sulgen 2013.

Boesch 1968

Jakob Boesch, Die Geschichte des Hofes Bernang und der Gemeinde Berneck, Berneck 1968.

Broder 1955

Leo Broder, Bernecker Töpferei, in: Rheintaler Almanach, 1955, 41-54.

Broder 1975

Leo Broder, Bernecker Töpferei. Ein geschichtlicher Rückblick, in: Unser Rheintal, 1975, 1-8.

Brongniart 1854

Alexandre Brongniart, Traité des arts céramiques ou des poteries considérées dans leur histoire, leur pratique et leur théorie ; Volume 2 ; édition avec notes et additions par Alphonse Salvétat, Paris 1854.

Creux 1970

René Creux, Volkskunst in der Schweiz, Paudex 1970.

Eisele 1929

Albert Eisele, Die Entwicklung des Hafnergewerbes in Kandern, in: Die Kachel- und Töpfer-Keramik 2, 1929, Heft 9, 65-71.

Eisele 1937

Albert Eisele, Von Kanderner Hafnern, in: Mein Heimatland 24, 1937, 138-154.

Frascoli 2004

Lotti Frascoli, Keramikentwicklung im Gebiet der Stadt Winterthur vom 14. -20. Jahrhundert: Ein erster Überblick, in: Berichte der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 18, 2004, 127-218.

Frei 1947

Karl Frei, Keramik des Mittelalters und der Neuzeit, in: Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich (Hrsg.), Ausstellung Schweizerische Keramik von der Urzeit bis heute, Zürich 1947, 27-46.

Gebhardt-Vlachos 1974

Sibylle Gebhardt-Vlachos, Kandern als Töpferstadt. Von der Bauerntöpferei zur Kunstkeramik, in: Das Markgräfler-Land. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Kultur des Landkreises Lörrach und seiner Umgebung. Neue Folge, 5/36. Jahrgang, 1974, Heft 3/4, 137-220.

Gresky 1969

Wolfgang Gresky, Hessische Töpfergesellen in Heimberg. Zu den Beziehungen zwischen hessischer und Berner Keramik, in: Historisches Museum Schloss Thun, 1969, 24-45.

Gross 1994

Uwe Gross, Hausrat an der Stadtmauer. Keramik- und Glasfunde aus dem Bereich der Befestigung der Katharinenvorstadt, in: Albrecht Bedal/Isabella Fehle (Hrsg.), Hausgeschichten, Bauen und Wohnen im alten Hall und seiner Katharinenvorstadt, Ausstellungskatalog (Kataloge des Hällisch-Fränkischen Museums Schwäbisch-Hall 8), Sigmaringen 1994, 359-388.

Gschwend 1948 (1931)

Robert Gschwend, Einiges über die Töpferei, in: Unser Rheintal (Wiederabdruck aus Rheintaler Schreibmappe 1931) 5, 1948 (1931), 81-82.

Heege 2010

Andreas Heege, Hohenklingen ob Stein am Rhein, Bd. 2: Burg, Hochwacht, Kuranstalt. Forschungen zur materiellen Kultur vom 12. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert (Schaffhauser Archäologie 9), Schaffhausen 2010.

Heege 2016

Andreas Heege, Die Ausgrabungen auf dem Kirchhügel von Bendern, Gemeinde Gamprin, Fürstentum Liechtenstein. Bd. 2: Geschirrkeramik 12. bis 20. Jahrhundert, Vaduz 2016.

Heege 2019

Andreas Heege, Keramik aus St. Antönien. Die Geschichte der Hafnerei Lötscher und ihrer Produkte (1804-1898) (Archäologie Graubünden – Sonderheft 7), Glarus/Chur 2019.

Heege/Kistler 2017

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Poteries décorées de Suisse alémanique, 17e-19e siècles – Collections du Musée Ariana, Genève – Keramik der Deutschschweiz, 17.-19. Jahrhundert – Die Sammlung des Musée Ariana, Genf, Mailand 2017.

Hoek/Illi/Langenegger u.a. 1995

Florian Hoek/Martin Illi/Elisabeth Langenegger u.a., Burg, Kapelle und Friedhof in Uster, Nänikon-Bühl (Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 26), Zürich, Egg 1995.

Kern 1879

Franz Xaver Kern, Geschichte der Gemeinde Bernang im St. Gallischen Rheinthale, Bern 1879.

Messerli Bolliger 1991

Barbara E. Messerli Bolliger, Der dekorative Entwurf in der Schweizer Keramik im 19. Jahrhundert, zwei Beispiele: Das Töpfereigebiet Heimberg-Steffisburg-Thun und die Tonwarenfabrik Ziegler in Schaffhausen, in: Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt 106, 1991, 5-100.

Obrecht/Reding/Weishaupt 2005

Jakob Obrecht/Christoph Reding/Achilles Weishaupt, Burgen in Appenzell. Ein historischer Überblick und Berichte zu den archäologischen Ausgrabungen auf Schönenbüel und Clanx (Schweizer Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters 32), Basel 2005.

Poeschel 1937

Erwin Poeschel, Die Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Graubünden, Bd. I: Die Kunst in Graubünden. Ein Überblick (Die Kunstdenkmäler der Schweiz 8), Basel 1937.

Schüly 2002

Maria Schüly, Hafnerware aus Kandern unter wechselnden Einflüssen, in: René Simmermacher (Hrsg.), Gebrauchskeramik in Südbaden, Karlsruhe 2002, 85-96.

Schwab 1921

Fernand Schwab, Beitrag zur Geschichte der bernischen Geschirrindustrie (Schweizer Industrie- und Handelsstudien 7), Weinfelden/Konstanz 1921.

Wellinger-Moser 2007

Margrit Wellinger-Moser, Von Ofenkacheln und Verenakrügen: Berneck war einst eine Hochburg für das Töpfergewerbe, in: Unser Rheintal, 2007, 249-258.