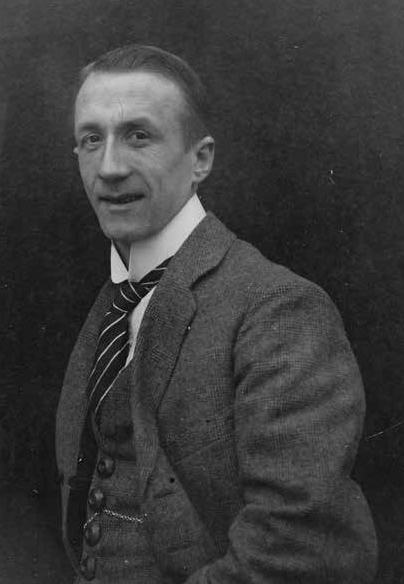

Heinrich Meister 1894-1972 (photo archive Meister & Co., Christine Hobi)

100 years of Meister pottery

Richard Kölliker 2020 (with additions from the SOGC by Andreas Heege)

Meister pottery in CERAMICA CH

Heinrich (also known as Heinz or Heinz-Tobias) Meister (born 7th July 1894 in Binningen near Basel; died 11th April 1972 in Dübendorf) grew up in Münster in the Alsace region. He sat his final school exams in Colmar and began studying architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich, where he met his future business partner, Josef Kövessi from Debrecen in Hungary. Kövessi studied political science and wrote his dissertation on the pottery industry in Switzerland (Kövessi 1923). In 1919, Heinrich Meister dropped out of university and undertook a work placement at Albert Wächter-Reusser’s art pottery in Feldmeilen near Zurich, where his tasks included the designing and painting of pottery. Josef Kövessi was already working there and, according to his work reference, by March 1920 had learnt all of the important ceramic techniques. The objects by Albert Wächter that have survived in the collection of the Swiss National Museum show that the workshop’s repertoire included the shapes and decorations that were typical of the time and looked similar to what was produced in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region during the same period. They were the sources of inspiration that Heinrich Meister and Josef Kövessi encountered during their brief training.

Dübendorf-Stettbach, the building where the pottery was produced in the 1950s (photo archive Meister & Co., Christine Hobi)

In 1920, thanks to support from Heinrich’s uncle, Albert Meister, Heinrich and his colleague Kövessi set up their own company which was known rather informally as “Meister & Kövessi, Workshop for Arts and Crafts” in Stettbach, a district of Dübendorf. Albert Meister had bought the property, which consisted of a house and a workshop building as well as an electric turbine. The premises had previously housed a potter’s workshop, a sawmill and a turnery. In later years Heinrich Meister would identify Josef Kövessi as the “actual founder” of the company. Kövessi was the ceramic specialist, while Meister acted as managing director, cashier, correspondent and ceramic designer. The Alsace master potter Alphons Braun was also briefly involved in setting up the workshop. His own stoneware factory in Thayngen had just closed down, which meant that Meister and Kövessi were able to purchase materials and machines for less than market value. A large wood and coal-fired walk-in muffle kiln was installed in the workshop. In the beginning it proved very difficult to regulate, and in 1925 it was replaced by an ultra-modern electric kiln. The muffle kiln, however, was not demolished and continued to be used alongside the new one, simply because of its size. Finding the right formulas for the glazes also appears to have caused difficulties at first. From the middle of 1920, however, production began in earnest. After various court proceedings, master potter Braun left the company even before it was officially formed.

On 1st January 1921, Heinrich Meister and his uncle were listed in the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce as owners of the “Meister & Cie.” art pottery workshop (SOGC 39, No. 29; p. 221 dated 30/1/1921). The company logo, however, read “A. Meister, art pottery workshop”.

1922 Mustermesse Basel, the Meister & Co. stand in group XII, Arts and Crafts (photo archive Meister&Cie, Christine Hobi).

In 1921, his first year of production, Heinrich Meister already took a stand at the Basel Mustermesse fair to present his collection.

Advertisement for MUBA (Mustermesse Basel), in the magazine “Die Tat, 5th March 1943”.

Over the course of its existence, Meister & Co. regularly presented its wares at the Mustermesse in Basel (official MUBA catalogues).

Pottery painter Gertrud Meister-Zingg (1898-1984) in her studio in the 1930s (photo archive Meister & Co., Christine Hobi).

Having applied and worked part-time for Meister & Co. in 1922, pottery painter Gertrud Zingg (born 2nd August 1898 in Bern; died 2nd March 1984 in Uster) from Bern joined the team full-time from March 1923. She had studied ceramics at the vocational school in Bern from the winter semester of 1914/1915 to the winter semester of 1918/1919 under Jakob Hermanns and others (cf. list of students in Messerli 2017, 228-229). Heinrich Meister and Gertrud Zingg married in August 1924. Gertrud was the head of the painting department in Stettbach. Their daughter Christine was born in 1927. She would begin an apprenticeship as a pottery painter in her parents’ company in 1947.

Benno Geiger (1903-1979) when he was employed at the Meister workshop (photo archive Meister & Co., Christine Hobi).

One of the company’s first apprentices from 1920 to 1922 was Benno Geiger from Engelberg (1903–1979). He worked as a journeyman for the workshop from 1923 to 1925. From 1935 to 1948 he was head of the department of art pottery at the Aedermannsdorf Pottery Factory and in 1941 he became the principal of the School of Pottery in Bern, a position he retained until he retired in 1969.

On 1st January 1924 the art pottery workshop “Meister & Co.” changed its structure (SOGC 43, No. 117, p. 901, dated 23rd May 1925). Heinrich’s mother, the widow Wilhelmine Meister, née Stehlin became a partner and retained the role until her death in 1948 (SOGC 66, No. 235, p. 2711, 7/10/1948). Following a dispute about the future course of the workshop, Josef Kövessi left the company in 1925 and returned to Hungary. Uncle Albert, on the other hand, emigrated to Brazil, where he lived from 1926 to 1930. He would eventually open up a shop selling colonial goods in Zurzach, Canton of Aargau.

On 13th October 1925, the NZZ (Neue Zürcher Zeitung) newspaper wrote: “The halls of the Kunsthalle [Bern] are decorated with the works of the artists of the Gesellschaft Schweiz. Malerinnen und Bildhauerinnen [Swiss Society of Female Painters and Sculptors]. The jury has shown reliable expertise in its powerful choices… Great advancements have also been made in the pottery category. Let me draw your attention to the beautifully formed bowls and plates by G. Meister-Zingg, or Clara Vogelsang’s accomplished jugs and bowls. Adele Schwander has delivered practical and pretty cups and bowls…”

In 1926, Heinrich and Gertrud Meister were admitted to the Schweizerischer Werkbund (SWB). Heinrich Meister became a member of the executive committee of the Zurich section of the Werkbund. Gertrud Meister-Zingg also became a member of the Swiss Society of Female Painters and Sculptors (GSMBK).

In 1927 the first vessels were exported to Germany, France and the Unites States. At that time the company mainly used faience glazes, only a small amount of slipware and many terracotta vessels, mainly large garden vases and moulded flowerpots. Other objects included small sculptures and animal figurines, garden statues and large planters made from sintered clinker as well as pottery with flowing glaze decoration typical of the period, and monochrome artistic glazes, craquelure, matte or alkali glazes. With his workshop’s designs Heinrich Meister also reacted to the “Neue Sachlichkeit” [New Objectivity] movement and the concept of unadorned pottery, which was becoming increasingly popular at the time.

In 1927 the Meisters exhibited some of their wares at the exhibition “Céramiques Suisses” at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire (Museum of Art and History) in Geneva.

In the 1930s, the company achieved its first successes. It began to present its wares at several other fairs, for instance in Frankfurt, and entered into a close collaboration with the Heimatwerk, a shop selling Swiss crafts and designs in Zurich. In 1931, Meister&Cie. took a share in the firm Wullschleger&Cie in Olten, which traded in furniture, gold and silver wares, pottery, wallpaper and fabric. This was obviously a bid to develop an additional channel of distribution (SOGC 49, No. 215, 2001 dated 16th September 1931). The renaissance of the Heimatstil (a historicist style of art and architecture) in the late 1930s in reaction to the Neue Sachlichkeit also left its mark on the workshop and its ceramics, as its clientele too were looking for products in this style. Heimatstil-type pottery was particularly popular with expats in the US, and so the Meisters began to produce vessels decorated with Alpine flowers, birds, fish, circus motifs, Alpine herdsmen, Ticino houses, Engadine houses, mottos, sports motifs etc. Heinrich Meister would later call this period a phase of “regression and original sin”. In 1939, Meister&Cie. also presented its wares at the 1939 Landesausstellung (Swiss National Exhibition) in Zurich.

Between c. 1930 and 1959, Heinrich Meister held the position of president of the Verband Schweizerischer Töpfermeister und Tonwarenfabrikanten (Swiss Association of Master Potters and Pottery Manufacturers), which was replaced in 1959 by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Schweizerischer Keramiker (ASK) (Swiss Ceramics Association), of which he was one of the founding members.

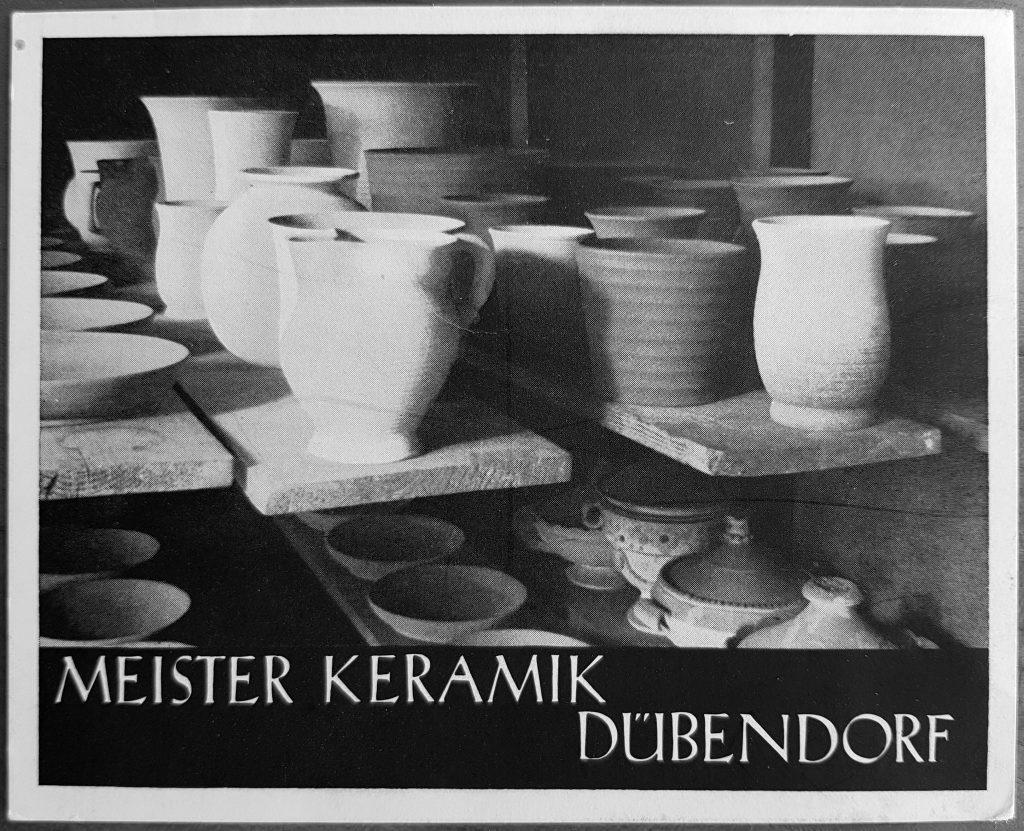

Promotional postcard for Meister Keramik, c. 1950.

After the Second World War, the company once again experienced an upswing in its fortunes, not least because contacts with the US could resume. However, much like German, Swedish and Canadian customers, the American clientele, too, expected the Meisters to launch a new and exclusive collection annually, which proved quite challenging for the designers and potters. After the war, up to 20 people were employed by the company at any one time. Many of the graduates from various Swiss Schools of Pottery worked for the Meisters for periods of time, including Annina Vital (who later had her own pottery in Chur) and Margret Loder-Rettenmund (later with Keramik Luzern). At the second International Ceramics Congress in Zurich in 1950, Heinrich Meister gave one of the main talks on the history of Swiss pottery.

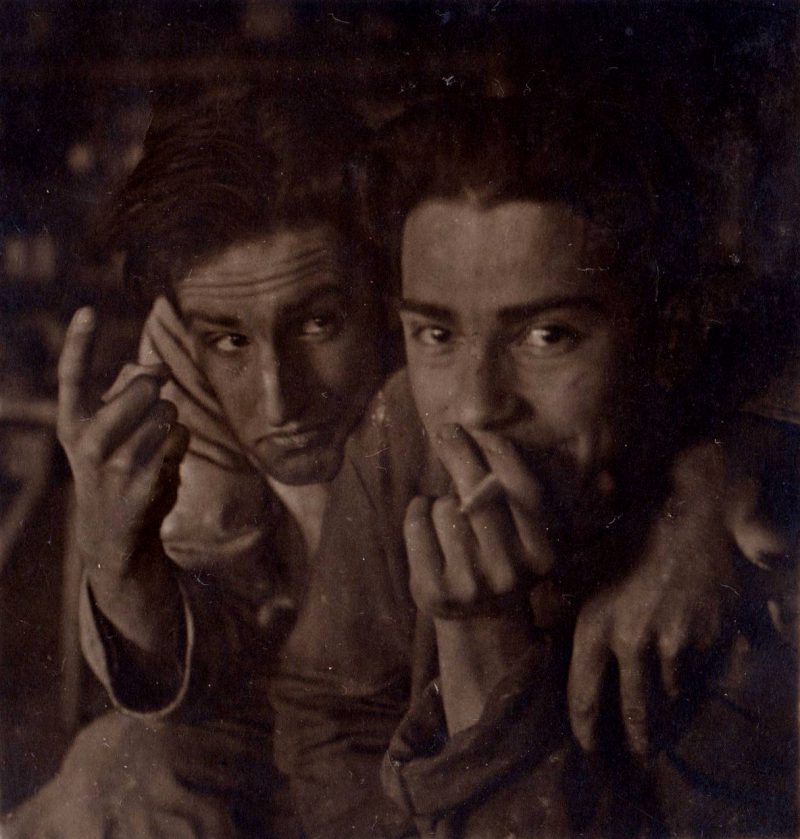

Heinrich Meister and Gertrud Meister-Zingg in the 1950s (photo archive Meister&Cie, Christine Hobi).

By the end of the 1950s, Heinrich Meister was beginning to make plans to close down the company in favour of opening a practical vocational school for mature students as a branch of the Migros Club School. The plans, however, were never realised and in 1961, the workshop shut its doors due to the owners’ ages and the decline in demand (Tages-Anzeiger, Zurich, 3rd January 1962).

Heinrich and Gertrud Meister-Zingg were part of the “second generation of modern Swiss ceramicists”, characterised by a desire to experiment with shapes, colours and decorations. On his second career path, Heinrich Meister became an internationally renowned “fashion designer” in pottery. He created shapes of striking originality and radiance. The most popular products included vases, lampshades and utilitarian pottery such as bowls and jugs etc., while Gertrud fashioned many different figurative objects besides painting pottery.

Several Meister ceramics can be found in the collections of the Schweizerisches Nationalmuseum (Swiss National Museum) and the Museum für Gestaltung (Museum of Design) in Zurich.

Exhibitions on and featuring Heinrich Meister:

Maria Weese and Heinz Meister, pottery exhibition, 6th July to 10th August 1924, Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich

Swiss National Exhibition “Landi”, ceramic pavilion, 1939, Zurich

“Den Meister zeigen” – Objects from the collection of Erika Munz and historical documents from the Meister business and family archives. 26th September to 18th October 2014, Protestant Parish Hall, Dübendorf.

Meister ceramics – a small collection of photographs

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Richard Kölliker, Vom Geschäft mit der schönen Form. Meister & Cie. – Kunstkeramische Werkstätte Dübendorf-Stettbach, 1920 bis 1961. Heimatbuch Dübendorf, Jahrbuch 68, 2014, 25-50.

Richard Kölliker, Meister-Keramik – Heinrich und Gertrud Meister-Zingg und ihre Kunstkeramik Werkstatt in Dübendorf-Stettbach 1920–1961. Privatdruck, Schaffhausen 2014.

Josef Kövessi, Die Tonwarenindustrie in der Schweiz. Diss., Universität Zürich, 1923.

Kupper, Roland, Auf der Suche nach der modernen Form: Meister-Keramik 1920-1961. Sammler-Anzeiger – Gazette des Collectionneurs 35, Nr. 4, 2015, 4.

Erwin Kunz, Aus der Vergangenheit der ehemaligen Töpferei Meister in Stettbach. Neujahrsblatt Zürich 11, Zürich 1966, S. 7-16.

Christoph Messerli, 100 Jahre Berner Keramik

von der Thuner Majolika bis zum künstlerischen Werk von Margrit Linck-Daepp (1987-1983). Hochschulschrift (Datenträger CD-ROM), Bern 2017.

Wegleitungen des Kunstgewerbemuseums der Stadt Zürich, Nr. 55, Keramische Ausstellung Weese, E. Maria und Heinz Meister, Zürich 1924.