“Heimberg-type” pottery from the Heimberg-Steffisburg region of the Canton of Bern in CERAMICA CH

“Heimberg-type” pottery from the Berneck region of the Canton of St Gallen in CERAMICA CH

Andreas Heege, Andreas Kistler 2019

Introduction

Heimberg and Steffisburg are two politically independent, neighbouring municipalities in the Canton of Bern. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, they, together with the area surrounding them, formed the most important location or region for pottery making within the Canton of Bern. Among collectors and in the literature, it has become customary to use the term “Heimberg” or “Heimberg pottery” for any ceramic object produced in the region, although as we will show, this is not strictly correct. Because it is often not possible to determine which workshop or municipality a particular piece originated from, we have opted, for the sake of convenience, to record the place of production as “Heimberg-Steffisburg”.

State of research

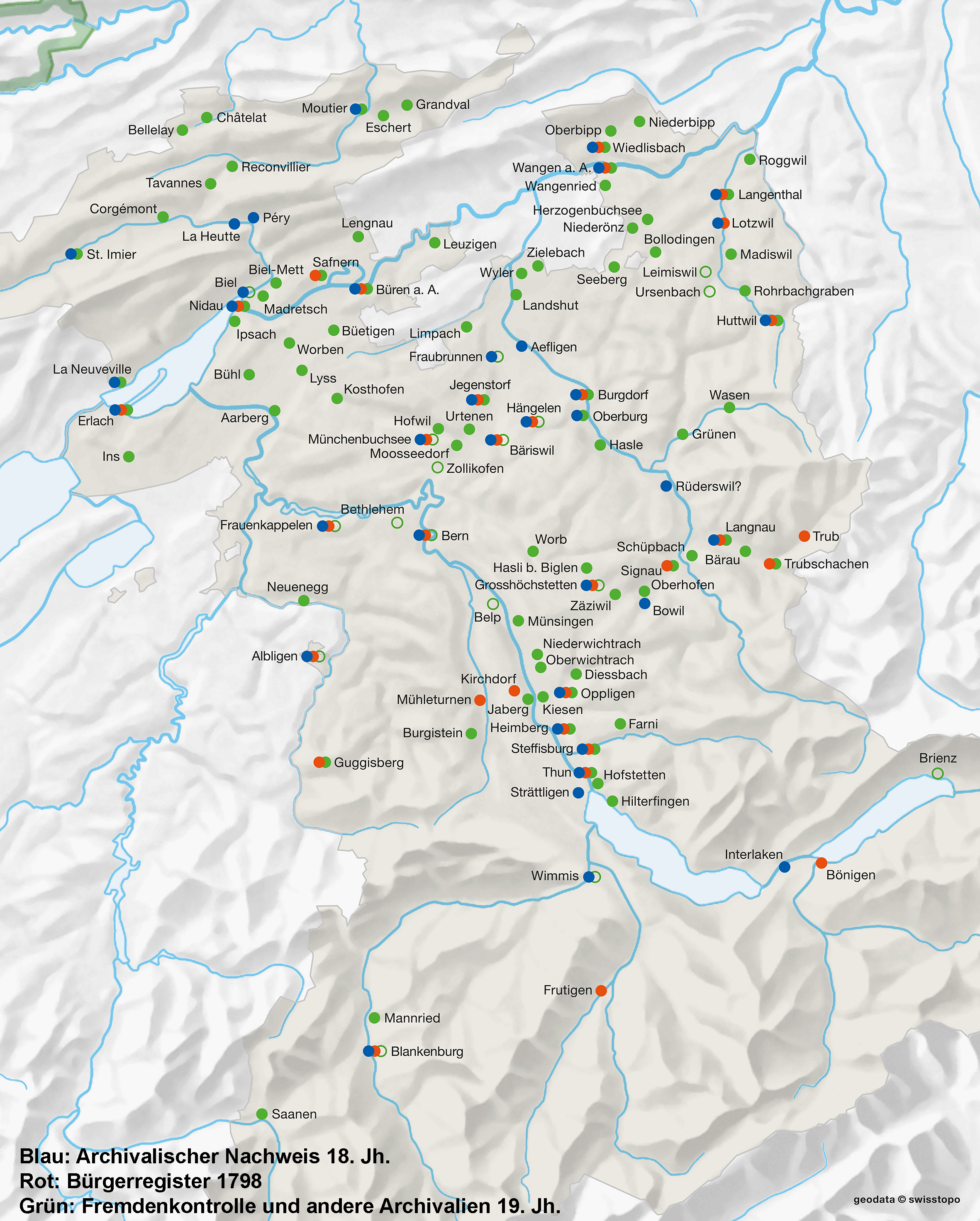

In c. 1850, up to 80 potters’ workshops existed along the road between Bern and Thun, in the former administrative district of Thun, and in a series of neighbouring municipalities that belonged to the district of Konolfingen – Jaberg, Kiesen, Oppligen, Diessbach, Wichtrach and Münsingen (Map of potters’ workshops in the Canton of Bern). Thanks to archival and genealogical research carried out by Fernand Schwab (Schwab 1921), Hermann Buchs (Buchs 1988) and Andreas Kistler, we now have a comprehensive overview of the locations of most workshops in Heimberg and Steffisburg and of the family backgrounds of the potters who ran them.

Heimberg-Steffisburg: List of potters’ properties

Heimberg-Steffisburg: List of potting families

At this stage it is not possible to determine which product came from which place of production. The term “Heimberg-Steffisburg” therefore generally refers to the wider Bernese region of production of “Heimberg-type” pottery. From around 1850 onwards, if not earlier, this would have included Langnau and neighbouring communities such as Schüpbach.

In 1764, Heimberg had 234 inhabitants in over 47 households, while Steffisburg right next to it had 924 inhabitants in 184 households. By 1856, the numbers in Heimberg alone had risen to 234 households with 1217 inhabitants. In 1880, Heimberg recorded 1149 inhabitants and Steffisburg 3898 (Heege/Kistler 2017a, 362–508).

Alexandre Brongniart (1770-1847), Director of the Porcelain Manufactory in Sèvres from 1800 to 1847, and his seminal work published in 1844 (source: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexandre_Brongniart)

The first information in the literature about the pottery that was being produced in Heimberg dates from 1844. Alexandre Brongniart, Director of the Porcelain Manufactory in Sèvres in France, visited the community in 1836. Eight years later he published a brief description of the local pottery and how it was being produced. As an eye-witness account by an experienced ceramicist it is highly significant (Brongniart 1844, Vol. 2, 14–15). Very few potters from Heimberg participated in the second or third Swiss Trade and Industry Exhibitions in Bern in 1848 or 1857, which is why the catalogues and technical reports compiled on those occasions did not paint a comprehensive picture of production at the time (Messerli Bolliger 1991, 46–47). It was not until 1874, in other words after the heyday of the indigenous pottery trade, that further, more detailed information was made public. Josef Merz, an architect from Thun, gave a public lecture on pottery production in the region and the harmful effects of lead poisoning, which potters typically suffered from (Merz 1874). The first overview of the history of the Heimberg potters was published in 1906 in the “Illustriertes Fremdenblatt von Thun und Umgebung”. It was written by Karl Huber, the then town archivist of Thun (Huber 1906), and is an important source of information about various events that occurred in the second half of the 19th century. Another source is a report by Oscar Blom published in 1908. At the time, Blom was director of the Trade Museum in Bern and responsible for “promoting the majolica industry in Heimberg-Steffisburg-Thun” (Blom 1908).

Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer (1864-1936), Director of the Museum of Cultures in Basel, and the pottery plates from his 1914 publication (source: MKB).

In 1914, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer, Director of what is today the Museum of Cultures in Basel (MKB), was the first to study Heimberg pottery from the point of view of cultural anthropology and to attempt to divide it into stylistic groups (Hoffmann-Krayer 1914).

In 1921, the solicitor and economist Fernand Schwab (1890-1954) published a study entitled Beitrag zur Geschichte der bernischen Geschirrindustrie, which was based on archival materials and interviews (Schwab 1921) and remains a seminal work and indispensable secondary source for anyone studying Heimberg pottery to this day.

It was not until between 1961 and 1995, that some life was once again breathed into Heimberg pottery research. This was mainly due to Hermann Buchs, the director of the Castle Museum of Thun (Buchs 1961; Buchs 1969; Buchs 1980; Buchs 1988; Buchs 1995), and Robert L. Wyss, director of the Historical Museum in Bern.

Robert L. Wyss (1921-2003), former director of the Historical Museum of Bern (source BHM) and his most important work on the history of pottery published in 1966.

Using the collection of the BHM, Robert L. Wyss attempted to compile a comprehensive classification system for all ceramic objects attributed to Heimberg (Wyss 1966, 34–42).

In her 1991 PhD thesis, Barbara E. Messerli Bolliger focused mainly on the history of late 19th and early 20th century pottery production in Heimberg (Messerli-Bolliger 1991).

In 2006, Adriano Boschetti published a summary of the state of research as part of his PhD thesis and shed a light on the history of Heimberg pottery production mainly from the point of view of cultural history and archaeology (Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 224–228).

Steffisburg, Grosses Höchhus, foundations of a potter’s kiln and stokepit from the 19th century (photo Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Heinz Kellenberger).

Steffisburg, Grosses Höchhus, pottery wasters from the infill between the foundations of the potter’s kiln, c. 1850-1860 (photo Archaeological Service of the Canton of Bern, Badri Redha).

It was not until quite recently that some of the potters’ workshops were excavated (Baeriswyl 2008; now also Heege/Kistler 2017b, 68 and most recently Frey 2022) and a potter’s kiln was recorded (Heege 2007a; Heege 2007b). A report on relatively large quantities of used Heimberg-type ware from sites in the city of Bern was published in 2010 (Heege 2010). In contrast to other potters’ workshops in the Canton of Bern, the potters in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region focused almost exclusively on producing crockery.

Tiled stove dated 1864 used specifically for drying raw and unfired vessels at the Künzi workshop “im Lädeli” in Heimberg. Reconstructed at the Castle Museum of Thun in 1999 but dismantled since, unfortunately.

Producing or fitting tiled stoves did not play a significant role (photo: an exception; Buchs 1970).

The early days of production

Pottery production in the Heimberg region began around 1730. It was at that time that Langnau potter Abraham Herrmann (1698–1750) and his family moved to Heimberg and later to Steffisburg. In c. 1752, Abraham’s younger brother Peter (1712–1764), followed him. Neither of the two had apparently been able to find gainful employment at their father’s workshop in Langnau. The earliest archival mention of Abraham dates from 29th April 1731. We can assume that Abraham and Peter, in their own workshops, continued to produce pottery in the “Langnau style” as they had learnt at home. However, this has not been confirmed by archaeological means or by ceramic objects with unambiguous signatures (on this see the current state of research as outlined in Heege/Kistler 2017b, 66–68, 268–271; Langnau workshop 1, hand 3).

The development of the craft in Heimberg

It was only after 1780, that external influences from southern Germany and northern Switzerland led to the development of a distinct “Heimberg style”, which included black-brown or red-brown coats of slip with slip-trailed decorations. Around the same time as Abraham Hermann moved to Heimberg, other potters from the Emmental valley – Huttwil, Langnau and Signau – and from eastern Switzerland – Herisau – also settled there. From c. 1770/80 onwards, archival records show that a growing number of foreign journeymen and sometimes potters, mainly from the region of Schaffhausen, and from Württemberg, Hesse and the Palatinate as well as Austria came into the region.

Plate by Johannes Weisshaubt from Neunkirch near Schaffhausen 1785 (SNM LM-011598, photo by Donat Stuppan).

A typical Heimberg plate, for example, bears the signature of potter Johannes Weisshaubt from Neunkirch near Schaffhausen and the date 1785 (SNM LM-011598). That year, 13 potters operated in the municipality of Steffisburg (Schwab 1921, 28; StAB BV101, 9).

According to the Helvetisches Bürgerregister (the cantonal register of citizens), 111 adult males lived in Heimberg in 1798, which included as many as 14 potters. One potter was registered in Opplingen and four in Steffisburg (Schwab 1921, 63). The local clay was obviously good to work with and there was a steady supply of firewood, despite the large number of craft enterprises

A report about a dispute over the building of a potter’s kiln in Steffisburg submitted to the economic commission of the Canton of Bern by Thun Bailiff Steiger in 1819 also mentioned the fact that, outside of the parish of Steffisburg, pottery was also being produced in Thun, Allmendingen, Jaberg, Diessbach near Thun and Langnau. He went on to say that there were currently 34 potters’ kilns in the parish of Steffisburg, one master potter would typically employ one or two journeymen, and sometimes an apprentice and a labourer. “Usually, only women and children are employed to dry the vessels, while women alone paint them. The journeymen that are currently working in the parish of Steffisburg include 10 non-nationals.” The running costs, including firewood, materials and workers’ pay were calculated at 60 francs per firing. After deducting expenses, one would expect to make a profit of 40 to 70 francs, depending on the type of pottery that was being fired. He also stated that production had markedly increased but that only a small amount of the wares was being sold within the Canton of Bern, so that “the rest can be sold in other cantons, or exported to France, Germany or Italy […]” (StAB B IV 15, Volume XI, 45–46). It is particularly worth noting in this context that the report states that decorating the pottery in Heimberg was a task carried out exclusively by women; a statement that would be reiterated in 1844 by Alexandre Brongniart. The exports mentioned in the report, particularly those to France and Italy, cannot be verified by the archaeological finds published so far.

In 1832, the State Governor of Thun wrote about the potters’ craft in Heimberg and its surroundings: “Pottery making is an important craft and it is being pursued on such a scale that several individuals have been able to build comfortable houses. Every week several fully loaded carts are driven into town.” (StAB A II 3401, p. 23, 6/12/1832, quoted after Frank 2000,766). In 1834, he reported that the potters had employed many journeymen from abroad, but that half were local. For each 55 local master potters there were five or six non-locals (StAB A II 3402, p. 13, 15/2/1834, quoted after Frank 2000, 766).

r the year 1836, Alexandre Brogniart (1844, 14) reported the existence of more than 50 potters’ workshops in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region.

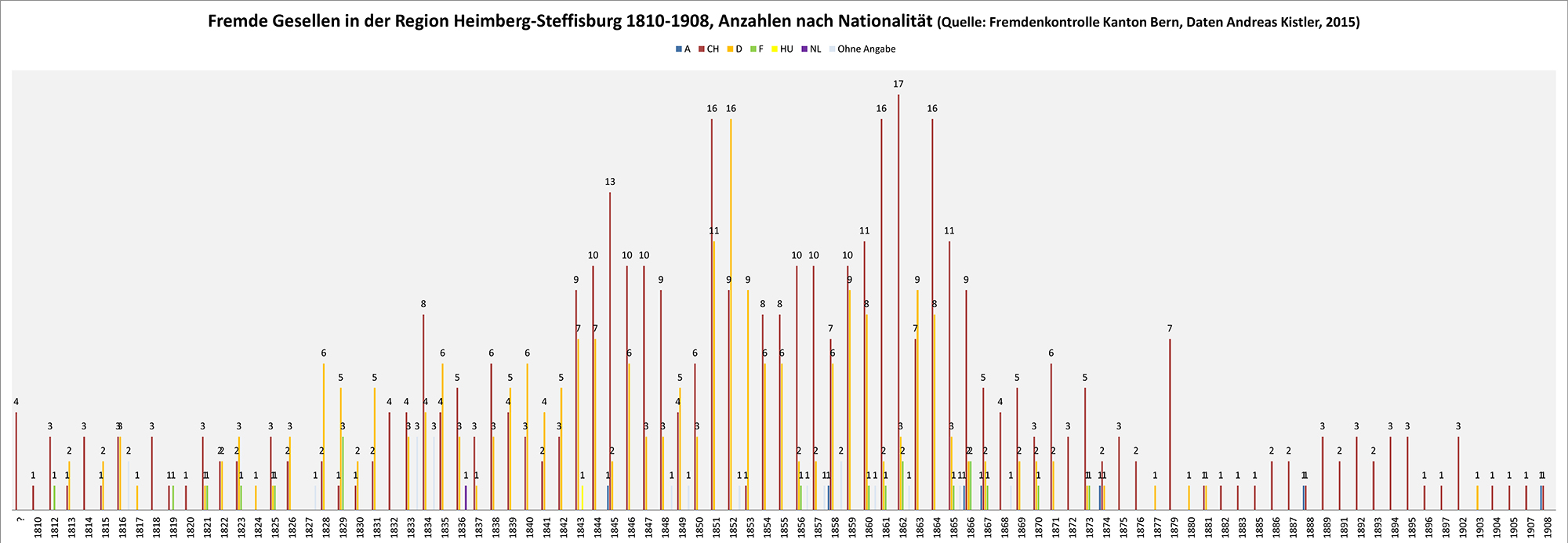

The influx of both Swiss and German journeymen to Heimberg continued unabated after 1800. For the period between 1810 and 1908, the archival sources include 401 journeymen from Switzerland (incl. Canton of Bern), 229 from Germany, 19 from France (Alsace), 7 from Austria and one each from the Netherlands and Hungary registered as working in the two relevant districts of Thun and Konolfingen (Bern State Archive, registry of foreign citizens). The vast majority of journeymen from Germany came from Baden and Württemberg, with much smaller numbers hailing from Bavaria, Hessen, Nassau, Prussia and Saxony. Many of the Swiss journeymen originated from the Cantons of Aargau (mainly Rekingen), Basel (Läufelfingen), Lucerne (Malters, Meggen), St Gallen (Berneck and places around Altstätten, Au, Balgach, Eichberg, Lüchingen, Marbach as well as Rapperswil, St Gallen), Schaffhausen (Beggingen, Neunkirch, Oberhallau, Unterhallau, Thayngen and Wilchingen), Thurgau (Berlingen, Steckborn), Vaud (Duillier, Poliez-Pittet) and Zurich (Bülach, Dällikon, Rafz, Schauenberg, Unterstammheim, Wädenswil and Zurich). They all brought what they had learned from making “Heimberg style” pottery (decorative techniques and motifs) back to their home cantons and states, thus ensuring the spread of this type of pottery.

If we assume that the records kept by the different registration offices were correct, there were never more than 27 foreign journeymen working in the region around Heimberg-Steffisburg in any of the years between 1809 and 1908, contrary to Schwab 1921, 85: “80 journeymen each year in the 1850s”. In their most productive years between 1843 and 1866, Heimberg workshops recorded more than ten new registrations each year. After 1866, the numbers fell below ten and between 1880 and 1908 there were only between one and three foreign registrations each year. The conflicts between the Swiss and German journeymen mentioned by Schwab (1921, 81) for the 1860s are clearly supported by the records. While nine German journeymen were registered in the Heimberg region in 1863 and eight in 1864, that number fell to three in 1865, two in 1866, one in 1867, and none at all in 1868. Eleven German journeymen in total were registered between 1869 and 1881. It must be borne in mind, however, that the Heimberg pottery trade appears to have experienced a period of crisis and undergone a phase of reorganisation at that time and as a consequence the number of Swiss journeymen also dropped significantly.

Alphabetical list of foreign journeymen (data provided by Andreas Kistler based on the records in the Bern State Archive)

List of foreign journeymen sorted by country, canton/state, place (data provided by Andreas Kistler based on the records in the Bern State Archive)

List of potters in the Canton of Bern employing foreign journeymen (data provided by Andreas Kistler based on the records in the Bern State Archive)

Heimberg vase made by journeyman Carl Traugott Lieberwirth from Strehla in Saxony (MKB VI-1432).

Direct ceramic evidence attesting to the presence of these journeymen in Heimberg is rarely found. So far, we only know of one Heimberg vase signed by journeyman Carl Traugott Lieberwirth from Strehla in Saxony (MKB VI-1432), who was employed by potter Christen Reusser in Kiesen for three-and-a-half months in 1829 (StAB Bez Konolfingen B 1434, 258). The Historical Museum in Bern houses another vase which is decorated with three-dimensional flowers and bears an incised motto and the signature of its maker on the bottom. The motto reads: Nicht wie Rosen nicht wie Nelken, den die vergehn u. verwelken, Sonder wie das Feuerglühn, soll stets unsre Freundschaft blühn, Heinrich Notter [Unlike roses and carnations, which wither and die, our friendship shall always endure like a glowing fire, Heinrich Notter] (BHM 6933).

Vase made by Heinrich Notter from Willisdorf in the Canton of Thurgau working as a journeyman potter in Heimberg (BHM 6933).

Heinrich Notter came from Willisdorf in the Canton of Thurgau. Between June 1860 and September 1868, he was employed by four different potters in Heimberg (StAB Bez. Thun Regstamt B 129). He may have brought this type of three-dimensional decoration from his homeland in eastern Switzerland, as similar objects are known to have been made by potter Martin Guhl (1825–1892) in Steckborn (1825–1892) (Früh 2005, 518). However, between 1844 and 1849, a Johann Martin Guhl from Steckborn (perhaps the same individual?) worked as a journeyman for four different potters in Hasle near Burgdorf, Diessbach, Kiesen-Murachere and Kiesen (StAB Bez Konolfingen B 1436). This means that he could have learnt to make this type of decoration in the Canton of Bern and brought it back to Steckborn.

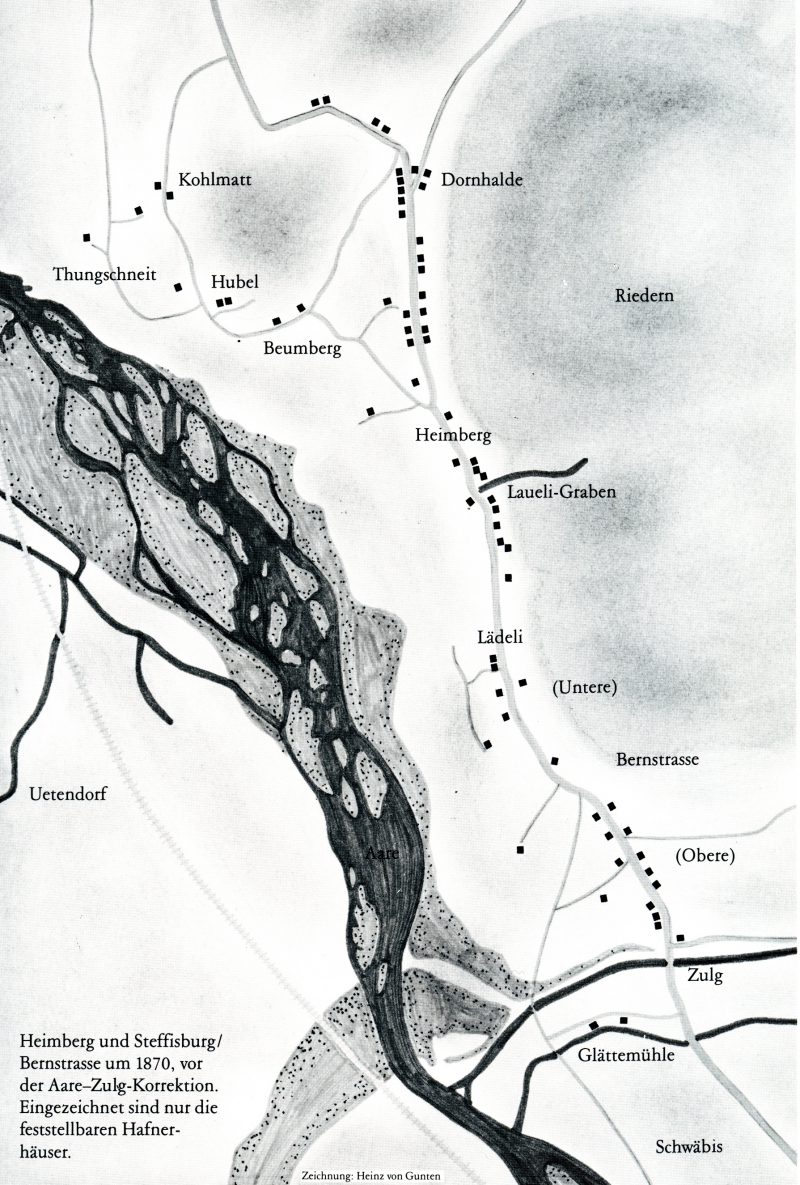

The distribution of potters’ workshops in Heimberg (Buchs 1988, 11).

Exact statistics to characterise the further evolution of the potters’ craft in the region are hard to come by, though it does appear that some 80 workshops were in operation in the Heimberg/Steffisburg region when pottery production was at its peak (c. 1820–1860) (for Heimberg see the map of potters’ workshops above; Buchs 1988, 11).

In 1860, a petition signed by 70 potters was submitted to the Bernese Government to advocate for the inclusion of potters’ products in the customs tariff negotiations with France. It was hoped that by convincing the French to lower tariffs on imports it would become viable to sell Swiss pottery in France (StAB BB IV 95).

In 1874, architect Merz from Thun reported that more than “62 independent potters are working with 53 kilns and employing 105 workers. The average annual production is therefore worth approximately 4000 Swiss francs per master. The average net profit is approximately 1500 francs. The overall turnover is therefore approximately 250,000 francs with a net yield of 93,000 francs. In normal times, like for instance now, there is considerably more demand than can be met, and if more could be produced, there would most certainly be greater demand, even if prices were to be increased. The potters, however, are still running their businesses in the same way as their grandfathers did before them, and in some cases production has even been reduced. This deficit is mainly due to the fact that the apprentices or journeymen do not seek further training, generally do not go abroad and therefore do not achieve any significant progress. The shapes of all vessels, and their basic colours and decorations remain the same and the products are still as unappealing as they always have been.” (Merz 1874, 23).

The Federal Census of Enterprises (commercial statistics) of 1889 recorded 41 potters’ workshops in Heimberg and 12 in Steffisburg. A total of 217 people made their living from pottery production (Gewerbestatistik 1889, cited after Frank 2000, 767).

The introduction of the so-called Thun majolica, a richly decorated historicist type of pottery aimed, in particular, at the tourist market which was developing at the time, resulted in strong sales for up to ten of the more innovative enterprises after 1870 and even more so after the Paris Exposition of 1878. We do not know if and to what extent some of the other potters were involved in producing for the same market, or for pottery wholesalers like Schoch-Läderach. What is clear though is that the majority of workshops did not become involved in producing modern “art pottery”, even after the end of the Thun majolica boom and the emergence of Art Nouveau pottery (between around 1900 and 1905) but continued to produce traditional utility wares. Due to their absence from museum collections and a lack of archaeological excavations, we know very little about what they looked like or how they were decorated..

In 1908, Oscar Blom, Director of the Trade Museum in Bern, counted 47 businesses in the region (Blom 1908, 3, without a list of names). The Adress- Reise- und Reklamen-Taschenbuch für Thun und Berner Oberland (a type of Yellow Pages for the Thun and Bernese Oberland regions) for 1908 lists the following potters, though we are not certain that they actually all produced crockery:

Heimberg (19 names) Aebersold Johann; Aebersold Gottlieb; Amstutz Elisabeth widow; Bieri Karl; Forster Johann; Gugger Chr.; Haueter Eduard; Hänni Friedrich; Jenni Robert; Kunz Fr.; Künzi Johann; Läderach Johann; Loder Bendicht; Portner Hermann; Reusser Jakob; Schädeli Fr.; Schenk Fritz; Schenk Rudolf; Tschanz Gottfried. Karl Schenk, who also produced and signed pottery is listed as a beekeeper and bailiff. Gottfried Tschanz also served as mayor.

Interlaken (2 names) Ritschard Karl, Centralstrasse; Straubhaar G., Rugenparkstrasse

Saanen (1 name) Loosli Jak.

Steffisburg (12 names) Bieri Ed., Bernstrasse; Frank Fr., Bernstrasse; Frank Chr., Bernstrasse; Hermann Rud., Bernstrasse; Hänni Gottl., Bernstrasse; Hodel Karl, Bernstrasse; Loder Karl, Bernstrasse; Meyer Fr., Bernstrasse; Messerli Gottfr., Bernstrasse; Müller Kl., Bernstrasse; Tschanz Joh., Bernstrasse; Zürcher Ed., Bernstrasse. The company owned by the widow Wanzenried-Ingold is listed as a “majolica factory”.

Strättligen (2 names) Feiler Gottl., Allmendingen; Straubhaar, Buchholz.

Wimmis (1 name) Loosli, Alfred

Zweisimmen (1 name) Gobeli, Hans

By the 1920s, the number had decreased to some 20 producers (Schwab 1921, 104, without a list of names), who were now increasingly listed as workshop owners with staff who had trained in one of the Swiss Schools of Ceramics or had attended pottery schools or courses (Chavannes or Bern, Steffisburg, Langnau). They understood the benefits of following the latest trends that were being disseminated, for instance, by the Basel Mustermesse trade fair, which had been set up in 1917.

According to the Federal Office of Culture, “peasant-style ceramics” are now considered a “living tradition” or “traditional craft”, even though very few potters’ workshops still exist in the region.

“Heimberg-type” pottery

In 1844, Alexandre Brongniart, Director of the Porcelain Manufactory in Sèvres, published a brief report on Heimberg and its pottery production:

“[…] it bears the distinct and assertive colouring that generally characterises Swiss decorative schemes. The small district of Heimberg, little more than a kilometre from Thun, on the road to Bern, has more than 50 potters. The clay body of their ceramics is composed of two types of clay from the local area: one is reddish and comes from Merlingen [Merligen, to be correct, on Lake Thun; Boschetti-Maradi 2006, 19], the other is from Steffisburg in Heimberg. Before firing, the mixture is a smoky grey in colour; natural earthenware slips or manmade slips dyed using a variety of metal oxides are then applied to colour the vessels. Red ochre is added to produce red vessels, manganese for brown and ferrous white earth is used to make them white. The unfired but well-dried objects are usually coated with these slips, which are then decorated with crude but extremely varied ornaments, using suspensions of clay dyed with adhesive oxides, including antimony, copper, cobalt and also manganese. The colours are put into small containers similar to lamps with quills in the spouts; using these containers, women add coloured dots, lines and other motifs to the vases; the variety of ornaments the potters use to decorate their products in such a simple manner is astonishing. The glaze simply consists of lead minium, which is added in the form of a powder to the unfired but well-dried pieces. The clay body, the coat of slip, the decorative patterns and the glaze are all fired together in a kiln that is shaped like a horizontal cylinder, has a sunken firing chamber, and is fuelled with fir wood […].” (Brongniart 1844, Vol. 2, 14–15 translated into German by Messerli Bolliger 1993, 149–150. The illustrations were published in Brongniart/Riocreux 1845, Pl. 31,4.12.13).

Pottery from Heimberg (Brongniart/Riocreux 1845, Pl. 31,4.12.13). No. 4 was acquired in Thun by the Museum in Sevres in 1817, while Nos. 12 and 13 were purchased by Brongniart in 1836.

The “Heimberg-type” pottery that was produced in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region was highly varied. It has still never been the subject of a comprehensive typological classification. Because the products from the region became the stylistic market leaders in terms of earthenware production in the 19th century, and also had a considerable influence on other pottery-producing regions in the Canton of Bern and the rest of Switzerland, it is really quite difficult to ascertain where exactly each individual piece of pottery was made. That is why we have opted to use the term “Heimberg-type” pottery. Where the provenance is given as “Heimberg-Steffisburg (region)”, this is a general term which explicitly refers to all pottery makers in the surrounding area of the Canton of Bern (including, for instance, Langnau products from the second half of the 19th century, cf. Heege/Kistler 2017b, 172-173). Similarly, the provenance “Berneck” is just an auxiliary concept which would definitely have included other places of production throughout the wider area – e.g. Steckborn in the Canton of Thurgau or perhaps even the Bregenz Forest region of Austria. The label “Berneck” comprises all “Heimberg-type” pottery that has been recorded mainly in museums throughout eastern Switzerland (in the Cantons of Graubünden, Appenzell, St. Gallen, Thurgau). From a stylistic perspective it is never possible to distinguish conclusively between “Berneck” ware and the pottery from the Canton of Bern. Owing to a lack of evidence, our assignations are still mainly being guided by our instincts.

Early Heimberg deep dish with hooked rim dating from 1783 (BHM 3189).

From around 1780, the range of “Heimberg-type” pottery began to include vessels with black, red and later white coats of slip (the earliest pieces dated from 1781: SNM LM-3509; SNM LM-18395, while others date from 1783: BHM 3189, MKW 219).

The insides and outsides of the vessels often differ in their colouring (black and red, black and white, red and white, dark red and orange-red), while others are coated in the same slip on both sides (red, white or beige) (Heege 2010, Figs. 67, 68-70, 73-79). Closed vessels such as jugs, pots or tureens always have a coat of white slip on the inside.

Heimberg-Steffisburg region, deep dish with hooked rim, dated 1793 (MAG R 222).

A second production line introduced in the Heimberg region around the same time was characterised by a coat of bright red or red-brown slip (e.g. MAG R 222). The oldest dated piece from this series is a plate with an unusual indented rim bearing a depiction of a dragoon made in 1784 (SNM LM-63935).

These wares were richly decorated with slip trailing, and sometimes the painted areas were then incised to further accentuate the shapes. Another technique used on this type of pottery was chattered decoration.

Deep dish with slip-trailed and incised decoration and with chattered decoration on its wall, c. 1800/1810 (MAG 7609).

Typical Heimberg plate bearing a potter’s motto“Ich bin der Vogel aller Ding, des Brot ich ess, des Lied ich sing” [I am the bird of all things, the bread I eat, the song I sing] (MAG R 220).

Plates and bowls often bore “potters’ mottos”. While some of which were reminiscent of those from Langnau, the majority had quite an international component undoubtedly owing to the journeymen’s migrations. By contrast to the Langnau examples, which were incised, Heimberg mottos were always slip-trailed. Combining slip trailing with combed or poured-slip decoration does not appear to have been a popular in Heimberg. The same workshops, however, probably also created wares with monochrome glaze or vessels with splashed decoration as well as pottery with speckled decoration. To answer the question of whether the wasters from the potter’s workshop at “Grosses Höchhus” in Steffisburg were representative of the wares commonly produced in the region (including sponged and dendritic decorations), further archaeological excavations of potters’ workshops would have to be undertaken.

The so-called “Thun majolica” was developed in the 1870s based on the “Heimberg style”, which was increasingly losing its original characteristics owing to the influences, on the one hand, of ceramics schools and drawing courses and on the other of Art Nouveau and Art Deco. It is therefore sometimes difficult to distinguish between “Heimberg-type” pottery and “Thun majolica”, particularly since the latter was produced in Steffisburg, both by independent workshops and by manufactories or small pottery factories such as the Wanzenried Manufactory.

From 1780, “Heimberg-type” plates, bowls and dishes typically had hooked rims while after 1800, they had mostly bevelled rims. Other characteristic shapes were lidded tureens and single-handled milk jugs. Coffee pots and cups have also regularly been found. Rarer shapes would have included water dispensers, wash basins, shaving basins, ink stands, tobacco jars, butter churns, plates with drainers, small deep dishes, candle holder, money boxes, oil lamps and lidded containers. Lidded preserving jars (for lard), or at least painted ones, however, appear to have been quite rare. No systematic overview of shapes has ever been compiled, either for the objects in museum collections, or for the finds from archaeological excavations.

Deep dish with bevelled rim, c. 1810/1820 (MAG R 242).

In the folkloristic literature, dishes and plates with bevelled rims (like MAG R 242) have long been considered typical of Swiss pottery. Researchers believe that they were imitated in the southern part of the Black Forest and in southern Central Franconia, including the coat of black slip and the decoration consisting of chains of S-shaped symbols along the rim (“Heimberg-type” pottery), when returning journeymen brought home the shapes and patterns they had encountered in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region (Groschopf 1937, 44; Spies 1964, 38, 39, 66; Bauer 1971, 51–52; Bauer/Wiegel 2004, 389). The opposite has also been suggested, i.e. that the style was brought to Heimberg from the southern areas of the Black Forest (Meyer-Heisig 1955, 39–43) but has not been adequately researched to date from the southern German perspective. Due to a lack of firmly-dated assemblages from Baden-Württemberg or Bavaria, it is not yet clear, when the transfer actually began. In any case, no dishes or plates with bevelled rims can be found in Schwäbisch Gmünd prior to 1817 (Gross 1999). When studying the literature as well as numerous collections from Swiss museums, it became clear that bowls, dishes and plates with bevelled rims were not part of the “classic” Bäriswil repertoire (prior to 1821), nor did they feature among Langnau products before the 1830s (Heege/Kistler/Thut 2011; Heege/Kistler 2017b). This means that the development of this particular type of rim in the 18th century did not take place within the core area of Bernese pottery production. The earliest firmly dated dishes and plates with coats of black or red slip from Heimberg from 1781 up to the 1820s also mainly featured hooked rims (cf. e.g. MAG N 686, MAG R 195; MAG R 221; MAG R 213; MAG R 240; MAG R244; MAG R 219; MAG R 222; MAG R185; MAG R 239). In museum collections, the earliest bevelled rims date from 1813 and increase in number in the following years (FMST K114, BHM 5876, Heege 2010, Fig. 75), and it is therefore no surprise that they were the dominant type of rim among the finds from Brunngasshalde in Bern (1787–1832) (Heege 2010, Figs. 67, 68, 70, 72, 74, 76 and 77). In archaeological contexts, their earliest appearance was on vessels with speckled decoration among the finds from the Alte Landvogtei site in Riehen in the Canton of Basel-Stadt, which were deposited in the ground no later than 1807. The same assemblage also included two shallow bowls with this type of rim (Matteotti 1994, Cat. 77 and 78, 92). This appears to support the theory proposed by Meyer-Heisig.

Categories of “Heimberg-type” pottery

The following overview does not claim to be exhaustive, as the “Heimberg-type” pottery has yet to undergo a comprehensive and detailed analysis.

“Heimberg-type” pottery with a coat of black or red slip, earliest phase

Plate dated 1792, bearing the potter’s motto “Die Rosen schmöcken lieblich die Knaben sind betriblich” [The roses smell lovely, the boys are busy] (MAG R 215).

The earliest “Heimberg-type” pottery, dating from the period between 1780 and c. 1820, had a coat of black or red slip and exhibited stylistic influences from the region around Schaffhausen and southern Baden-Württemberg. The same technique and colour scheme would continue to be used until the second half of the 19th century; the painted motifs, however, would change as time went on (Heege/Kistler 2017a, 378-411).

“Heimberg-type black and red” dishes with bevelled rims, younger motifs, c. 1840-1860 and c. 1865-1870 (MAG R 216 and R 234).

“Naïve Heimberg-type” pottery

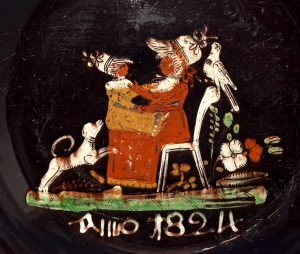

A more independent local group of decorations and motifs evolved from the early 19th century onwards (cf. e.g. MAG R 241; MAG 7312; MAG 16699; MAG R 212; MAG R 194; MAG R 217; MAG R 218; MAG R 223; MAG 971). The depictions were naïve in style often showing small child-like figures dressed in adult clothes or uniforms and performing the activities of adults.

Most of the clothes were in the post-revolutionary Empire or Biedermeier styles, which are particularly easy to recognise in female fashion. This group of objects began to appear in 1808 at the latest and were probably all produced by a single or small group of pottery paintresses or workshops. The earliest known piece bears a depiction of a potter and a pottery paintress in their workshop (BHM 7943). The most recent piece in the series dates from 1832 (MKB VI-2821). There may have been a second paintress who had a similar style of working and who succeeded the first one chronologically, producing pottery until at least 1856 (e.g. BHM 8751; Heege 2010, Fig. 78; see also CREUX 1970, 130,5).

“Heimberg-type” pottery with draped swags

Another large group of “Heimberg-type” pottery mainly comprised dishes, bowls, plates and tureens with draped swags. This type of overall decoration that went up as far as the rim and was reminiscent of interior textile decorations, was part of the Empire or Biedermeier styles (cf. MAG 12016; MAG AR 1999-97; MAG R 234).

Unfortunately, very few of these dishes bear dates so that it is almost impossible to determine their age. There are, however, some chronological clues. A few examples bear short draperies consisting of just one or two swags that can be dated to 1802, 1815, 1817, 1820 and 1828 (SNM LM-4816; MKB VI-5125; SNM HA-4250; NH-KL NH2000-025; MKB VI-977). Overall triangular swags first appeared on plate rims in 1817 and 1819 (SNM HA-4250; MKB VI-3932). It is therefore no surprise that similar motifs can also be found on some of the vessels recovered from municipal waste deposited at Brunngasshalde in Bern prior to 1832 (Heege 2010, Fig. 74). However, draped swags of this kind can also be found on a dish dated 1867 (SST 5186) and a tiled stove dated 1864, which was used in potter Johann Künzi’s workshop in Heimberg for drying ceramics (Buchs 1970). The next stage in the development of this type of decoration in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, eventually led to the almost all-over decoration known as Chrutmuster [herbal or plant pattern] on “Thun majolica” (Blaettler/Ducret/Schnyder 2013, Pl. 73,1).

“Heimberg-type” pottery with a coat of white slip and incised and slip-trailed decoration

Alongside the pottery coated in black or red slip, a third production line evolved in the Heimberg-Steffisburg region from the early 19th century, which was coated in white slip and decorated with incised and slip-trailed motifs (e.g. MAG 7610, MAG N 30, MAG 4638, MAG 7608, MAG 4640, MAG R 165, MAG AR 2025-383, MAG 16697; Heege/Kistler 2017a, Kat. 145-152). As in the pottery from “Langnau”, its motifs were also first outlined using an incisor tool and then filled out using a slip trailer. Parts of motifs were sometimes slip-trailed only. The same production line also had a series of plates with black or red rims and white wells (see MAG 14093) or with black or red wells and white rims. The backs of these plates could also be coated in red slip. The entire series is not very well dated.

Keramik “Heimberger Art” (MAG 7610 und 14093).

If the dates incised or painted onto the objects are correct, the oldest vessel to be decorated in this manner is a plate from 1805 (SST 06773), followed by two shaving basins dated 1813 and 1829 respectively (RML A78; private ownership), a coffeepot with a pedestal base dated 1814 (MKB VI-2881), a dish dated 1819 (HMTG T225), a plate dated 1820 (SST 569), a coffeepot dated 1827 (MKW 229), a vase made by the journeyman potter Carl Traugott Lieberwirth from Saxony, which can be dated to 1829 (MKB VI-1432) and a coffee cup and saucer dated 1830 (BHM 8424, Heege 2010, Fig. 69). The Thun Castle Museum houses a bowl for cream dated 1831 (SST 11132) and a plate dated 1831, which bears an inscription identifying its place of production as “Heimberg” (SST 12680). These dates are supported by archaeological finds. Pottery of this type was deposited in the ground between 1820 and 1836 in Wimmis, Canton of Bern (Archaeology Service of Bern, FpNr. 340.013.2011.01) and prior to 1832 in municipal waste found at Brunngasshalde in Bern (Heege 2010, Fig. 68,2). The decorative evolution of this group, however, continued beyond that time, probably up to around 1850/60. The group overall can probably be dated to the first half of the 19th century with an emphasis on the period between 1820 and 1840.

The link to Heimberg as a potential place of production for this ware is not just based on the vase created by Carl Traugott Lieberwirth for potter Christen Reusser in Kiesen (MKB VI-1432) or the plate from the Castle Museum in Thun (SST 12680), but also on a few specimens that, based on their motifs, can be associated with the same workshop in Heimberg that created the “naïve” decorations. Children in dragoons’ uniforms and other children dressed as adults can also be found on vessels coated in white slip (ZHdK-KGS 01100; MKB VI-2217; SNM HA-4255, LM-45843). The women’s dresses all have fitted bodices ending just below the bust, as one would expect to find given the Swiss adherence to French fashion during the Helvetic Republic, the period after the Act of Mediation and the period of Restoration, in other words up to the 1830s. The coat of arms of the Canton of Bern was also very popular in this series (MAG 7610, MAG 7608). It can be found not only on a cup dated 1830 (BHM 8424; Heege 2010, Fig. 69), but also on several plates (BHM 12549, BHM 12580; MKB VI-2216), shaving basins (RML A80; BHM 2594, BHM 21232) and even a coffee pot (MAG 4638).

“Heimberg-type” pottery with blue slip trailing

Blue slip trailing on “Heimberg-type” pottery began very tentatively in the late 1820s (MKB VI-1432) but then very quickly became more popular. Five plates and dishes coated in white slip from the Museé Ariana in Geneva are stylistically linked by this novel blue colour, which tended to run more than other colours (MAG 7608, MAG 4640, MAG R165, MAG AR 2015-383; MAG 16697, compare also MAG R 216, MAG 14093).

In addition, MAG 7608 and MAG 4640 also share the same decoration on the rim, which consists of round or rosette-shaped petals and round green leaves accompanied by rows of dark-brown dots. MAG 4640 and MAG R 165, on the other hand, both bear draped swags of the type mentioned above (see Heege/Kistler 2017a, Kat. 148-152). The border made up of petals and leaves evolved from the 1820s onwards, although the dark-brown dots appear to have been absent during the early period, as can be seen from a coffee pot dated 1836 that is now housed at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (FWMC C.1910-1928). The complete pattern can be found on two plates dated 1837 and 1838 respectively (SNM LM-010321; MAHN AA-1462) and on a costrel dated 1842 (MKB VI-10765). A small number of dated reference pieces are from 1848 (private ownership; Albert Anker Haus in Ins), 1853 (BHM 5874; MKB VI-1765), 1857 (BHM 6937), 1858 (MTrub 677), 1863 (SST 4896) 1864 (MAHN AA-2023) and 1871 (MKB-1423).

“Heimberg-type” pottery with slip trailing only and with very runny blue slip trailing

“Heimberg-type” pottery decorated with slip trailing that did not have incised outlines (cf. MAG 14205, MAG R 152) appears to represent a reduced variant or later phase of development.

Usually, several different colours were combined. Often very runny, blue was either the main colour or at least an important one. The oldest known piece to bear polychrome slip trailing that includes blue is a shaving basin dated 1862 (private collection in Cham). Dated objects are otherwise rare. They include a tureen dated 1869 (RSB IV-924), two plates with drainers dated 1874 (SNM LM-011799, SNM LM-017871) and two shaving basins dated 1874 and 1877 respectively (Augustinian Museum, Freiburg i. Br. 2008/041; MBS 1920.129). The group includes other pieces that bear the coat of arms of the Canton of Bern, a small tureen (MKW 265), coffee cups and saucers (SST 4898) and a milk jug (SST 4904).

The earliest firmly dated objects decorated with cobalt blue painting only and dark-brown writing are from 1854 (private Swiss collection).

Based on a signed shaving basin (SST 649), this style, sometimes combined with polychrome slip trailing is often attributed to a single workshop and to potter David Andres in Heimberg (1810–1873; Buchs 1988, 94; Wyss 1966, 40; Messerli-Bolliger 1991, 47–48; Roth-Rubi/Schnyder/Egger/Fehr 2000, 6–10; Boschetti-Maradi 2007, 58–59).

However, given that some of these objects are dated to periods more than 11 years after David Anderes’ death (up to 1884), this is no more convincing than attributing them all to the Loosli workshop in Wimmis as proposed by Fernand Schwab (Schwab 1921, 106 fn. 72). There is no evidence to suggest that only one workshop in Heimberg produced blue painted vessels. Master potter Christian Matthys in Heimberg, for instance, created very similar wares in his workshop on Dornhalde in 1872 (MKB VI-3919).

Ceramic fragments with a coat of white slip and partial blue decorations dating from the first half of the 19th century are known to have been produced by a workshop in neighbouring Steffisburg (Heege 2012, Fig. 12). And finally, after 1840 (Heege/Kistler 2017b, 117 Fig. 138), and particularly after the mid-19th century (Heege/Kistler 2017b, 173), potters in Langnau also made intensive use of runny blue slip trailing.

“Heimberg-type” pottery – Neo-Renaissance

The striking elements of the small box MAG R 179 are laurel swags and Neo-Renaissance-style masks in between. This particular historicist style developed in France after 1830 (under the “Citizen King” Louis-Philippe) and was characterised by the conscious return to Renaissance-style elements, with local variants all over Europe. The style was apparent in architecture, interior design, artisanship, cabinet making and pottery production. It had its greatest impact between 1870 and 1885, when its forms were considered exemplary. The box shown here has six counterparts, five in Swiss museums and one in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, none of which are dated (FWMC C.1944-1928; ZHdK-KGS 01972; MAHN AA 1198, MAHN AA 2056). The slip trailing on two of them is blue instead of green (RSB O-5361; SNM LM-010327). No other types of pottery with similar sprigs are known. Their place of manufacture is unclear. The fact that they exhibit rows of dark-brown dots, along with some relevant information about their provenance in museum inventories points to the Heimberg-Steffisburg region. The example in the Fitzwilliam Museum was purchased in 1894 from antiques dealer Samuel Born-Straub, or from his daughter Margarethe in Thun. Two boxes as good as new from the Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel were acquired from the collection of Edouard de Reynier in Bern as early as 1887.

There are no specific clues that would point to the date of these boxes. Given the earliest date of entry into one of the museum collections, they must have been made prior to 1881, when the then Museum of Design in Zurich acquired its piece (ZHdK-KGS 01972) from a dealer in Schaffhausen. Bearing in mind that the Neo-Renaissance style was considered the height of fashion in the 1870s, it would be interesting to know where the potter or potters in Heimberg got their inspiration from. It is possible that this is where Eugène Boban (1834–1908; Riviale 2001) enters the picture. Considered a highly controversial figure today for his forging of antiquities, he was an enterprising Parisian dealer who in the 1860s convinced two Heimberg potters, Wyttenbach and Küenzi, to produce “luxury ware” to his designs (Huber 1906, 278).

“Heimberg-type” pottery – white slip over black-brown slip

One of the plates in the Musée Ariana in Geneva (MAG R 188) belongs to a relatively large group that began with examples dated 1849/1850 (private ownership and SNM LM-010323) and was produced until at least 1871 (MKB VI-15780).

The mottos on the plates were written either in a semicircular banner, as in the examples shown above, or in a circle in the centre (MAHN AA1232; MAHN AA1457; HMO 8357). What makes this group stand out is the fact that they have two coats of slip – one in black-brown, the other, covering the first, in white. Because the incised decoration only removed the white slip, the patterns appeared dark-brown or even black. Sometimes, the lead glaze slightly etched the black slip, so that it left brown smudges along the edges of the incised lines. The decorations on Langnau pottery and on wares from other German-speaking parts of Switzerland, however, were always incised down to the clay, resulting in red or red-brown patterns.

There are hardly any references to this particular decorative technique in the literature. Published in 1906, an article by Thun’s city archivist, Karl Huber, is the only time it is referenced, though he neglects to suggest a date for when it was first employed (Huber 1906, 278). The earliest use of the technique dates back to the 1830s. The Swiss National Museum houses a plate dated 1837 (SNM LM-010321), which at first glance appears to be more recent.

The incised date, however, is supported by a plate with a similar base that is also dated 1837 and another that bears the date 1838, both in the Museum of Art and History in Neuchâtel (MAHN AA 2164; MAHN AA 1462). The same date can also be found on two identical “Heimberg-type” tureens bearing this type of decoration (private ownership; MKB VI-1783). From around 1840 onwards, numerous workshops seem to have been using the same technique, judging by the variety of decorations and designs that exist (cf. also MAG 14206; MAHN AA 1453; MAHN AA 2184; MAHN AA 3276; MAHN AA 1233; MAHN AA 2042; MAHN AA 2023; MAHN AA 1430; MAHN AA 1455; MAHN AA 1456; MAHN AA 1431; MAHN AA 1232; 1457). They also include objects dated between 1843 and 1877 with patterns that were only incised and not painted (MAHN AA 1453; almost identical: RSB IV-599).

One serving dish for a tart or cake dated 1875 is known to have been decorated by a Mrs. Imhof, née Frank, from Heimberg (FWMC C.1950-1928). It should therefore come as no surprise that the same technique can also be found on late Thun majolica vessels (Huber 1906, 279; MAHN AA 1764; MAHN AA 1989-60; MAHN AA 1416; MAHN AA 1417; MHLCF No 6). Heimberg potters were not alone in using this technique. The works that Steckborn potter Martin Labhardt produced for Peter Herrmann’s (1809–1871) workshop in Langnau included objects with similar decorations from 1853 and possibly from other years (MAHN AA 2055; Heege/Kistler 2017b, 381–386).

Beaded decoration

Some “Heimberg-type” vessels had “beaded decoration”. The questions of where this group of “Heimberg-type” pottery originated, when it was first produced, how it evolved and how it was linked to the pottery from Langnau (see the glossary entry Beaded decoration), can only be rudimentarily answered. This is due to the fact, for instance, that so far, none of the archaeological finds from the 19th century in the Canton of Bern have included any vessels with beaded decoration. Nor did the technique feature among the production waste from Steffisburg, Höchhus (Baeriswyl 2008, before 1855) or Langnau, Sonnweg 1 (Heege/Kistler 2017b, 154–183).

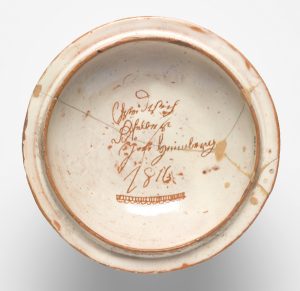

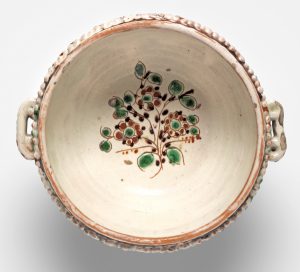

Box with beaded decoration from 1816 (MAG R 178), made by potter Friedrich Gfeller in Oppligen “beir Rotachen Brügg”.

In this respect, the box MAG R 178 is an outstanding object. It not only bears a date (1816) but also the name of the potter who made it (Friedrich Gfeller) and a possible place of manufacture (“ÿm Heimberg”). Only one other mention of this potter has so far come to light. In 1829, he is known to have lived in Oppligen “beir Rotachen Brügg”, in other words, right next to Heimberg. We also know that a Hans Gfeller had a potter’s workshop there from 1827 to 1829 (StAB Bez Konolfingen B 1434). If we deduce from this that beaded decoration originated from the Heimberg-Steffisburg region, this is further supported by information supplied by Karl Huber, Thun’s city archivist. In his article in the “Illustriertes Fremdenblatt von Thun und Umgebung” he writes about the history of Heimberg pottery production: “In the early 19th century, Heimberg was re-energised. A new, unusual type of decoration was introduced: little balls of clay were attached to the vessel surfaces in rows, arches or other small groups. The predominant colours added to the greenish-white slip were emerald-green, brick-red, a deep yellow and sometimes brown […]” (Huber 1906, 278).

Beaded decoration can be found on many “Heimberg-type” ceramic objects in museums, including on boxes, tureens, money boxes, vases, milk jugs and coffeepots, all of which are coated on both sides with white slip and probably all date from the first or second third of the 19th century (MAG R 178, MAG 16698, MAG AR 2015-364, MAG N 850, MAG AR 2015-366, MAG N 196). The box MAG R 178 mentioned above is one of only two known objects with this type of decoration that bear a date. The other is a money box dated 1859 from the Regional Museum in Langnau (RML A306). The laurel garland and the rouletted beading beneath the rim may point to a somewhat later date for MAG N 196, but this cannot be confirmed by other dated pieces.

However, since many of the lids on the white boxes and tureens with beaded garlands also bear reduced or advanced versions of volute handles, which were typical of Langnau ware (MAG AR 2015-364, MAG N 850, MAG N 196), we might ask what exactly was happening in the first two thirds of the 19th century and who copied what from whom. In other words, are we looking at Heimberg products with earlier decorations and handle types from Langnau or are they Langnau wares with decorative motifs from Heimberg? Pottery with beaded decoration is an obvious manifestation of the close ties between the two areas and also heralds the end of the Langnau style and the increasing predominance of Heimberg-style decorations even on products from Langnau. In the absence of new archaeological finds from the areas concerned, the question of where these wares were actually made will continue to be difficult to answer. The boxes and tureens in the collection of the Musée Ariana in Geneva (MAG R 178; MAG 16698, MAG AR 2015-364, MAG N 850, MAG AR 2015-366, MAG N196) were probably made in Heimberg. Conclusive evidence for the production of such vessels with beaded decoration and incised flower/leaf motifs in Langnau has not yet been found.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Baeriswyl 2008

Armand Baeriswyl, Steffisburg, Grosses Höchhus. Bauuntersuchung und Grabung seit November 2006, in: Archäologie Bern/Archéologie bernoise. Jahrbuch des Archäologischen Dienstes des Kantons Bern, 2008, 72–75.

Bauer 1971

Ingolf Bauer, Treuchtlinger Geschirr (Kunstwissenschaftliche Studien 45), München 1971.

Bauer/Wiegel 2004

Ingolf Bauer/Bert Wiegel, Hafnergeschirr aus Franken (Kataloge des Bayerischen Nationalmuseums München 15,2), München 2004.

Boschetti-Maradi 2006

Adriano Boschetti-Maradi, Gefässkeramik und Hafnerei in der Frühen Neuzeit im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 8), Bern 2006.

Boschetti-Maradi 2007

Adriano Boschetti-Maradi, Geschirr für Stadt und Land. Berner Töpferei seit dem 16. Jahrhundert (Glanzlichter aus dem Bernischen Historischen Museum 19), Bern 2007.

Brongniart 1844

Alexandre Brongniart, Traité des arts céramiques ou des poteries considérées dans leur histoire, leur pratique et leur théorie, Paris 1844, Bd. 2.

Brongniart/Riocreux 1845

Alexandre Brongniart/D. Riocreux, Description méthodique du Musée céramiques de la manufacture royale de porcelaine de Sèvres, Paris 1845.

Buchs 1961

Hermann Buchs, Über die Anfänge der Töpferei in Heimberg und deren Eigenständigkeit, in: Jahresbericht Historisches Museum Schloß Thun, 1961, 5–12.

Buchs 1969

Hermann Buchs, Heimberg. Aus der Geschichte der Gemeinde, Heimberg 1969.

Buchs 1970

Hermann Buchs, Ein Heimberger Tröckneofen, in: Historisches Museum Schloss Thun, 1970, 4–17.

Buchs 1980

Hermann Buchs, Die Thuner Majolika des Johannes Wanzenried und des Zeichners Friedrich Ernst Frank, in: Jahresbericht Historisches Museum Schloss Thun, 1980, 5–43.

Buchs 1988

Hermann Buchs, Vom Heimberger Geschirr zur Thuner Majolika, Thun 1988.

Buchs 1995

Hermann Buchs, Das Hafnergewerbe im Heimberg, in: Einwohnergemeinde Heimberg (Hrsg.), 850 Jahre Heimberg 1146-1996, Heimberg 1995, 50–60.

Blom 1908

Oscar Blom, Die Förderung der Majolika-Industrie in Heimberg-Steffisburg-Thun durch das kantonale Gewerbe-Museum in Bern, in: Jahresbericht pro 1907 des kantonalen Gewerbemuseums Bern, 1908, 1-9.

Frey 2022

Jonathan Frey, Archäologische Forschungen: Töpferöfen in Heimberg, in: Keramikfreunde der Schweiz, Bulletin 99, 2022, 13-16.

Groschopf 1937

Günter Groschopf, Die süddeutsche Hafnerkeramik, in: Jahrbuch des Bayerischen Landesvereins für Heimatschutz, 1937, 37–115.

Gross 1999

Uwe Gross, Schwäbisch Gmünd-Brandstatt: Keramikfunde aus einer Kellerverfüllung der Zeit um 1800. Eine vorläufige Übersicht. Teil 1: Irdenware, in: Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 23, 1999, 667-720.

Heege 2007a

Andreas Heege, Der letzte Töpferofen im Heimberg, in: Jahresbericht Schlossmuseum Thun, 2007, 27–37.

Heege 2007b

Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen-Pottery kilns-Fours de potiers. Die Erforschung frühmittelalterlicher bis neuzeitlicher Töpferöfen (6.-20. Jh.) in Belgien, den Niederlanden, Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (Basler Hefte zur Archäologie 4), Basel 2007, 309–319.

Heege 2010

Andreas Heege, Keramik um 1800. Das historisch datierte Küchen- und Tischgeschirr von Bern, Brunngasshalde, Bern 2010.

Heege/Kistler/Thut 2011

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler/Walter Thut, Keramik aus Bäriswil. Zur Geschichte einer bedeutenden Landhafnerei im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 10), Bern 2011.

Heege 2012

Andreas Heege, Drei neuzeitliche Grubeninventare von Jegenstorf, in: Archäologie Bern/Archéologie bernoise. Jahrbuch des Archäologischen Dienstes des Kantons Bern, 2012, 159-196.

Heege/Kistler 2017a

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Poteries décorées de Suisse alémanique, 17e-19e siècles – Collections du Musée Ariana, Genève – Keramik der Deutschschweiz, 17.-19. Jahrhundert – Die Sammlung des Musée Ariana, Genf, Mailand 2017, 362–508.

Heege/Kistler 2017b

Andreas Heege/Andreas Kistler, Keramik aus Langnau. Zur Geschichte der bedeutendsten Landhafnerei im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 13), Bern 2017.

Hoffmann-Krayer 1914

Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer, Heimberger Keramik, in: Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde 18, 1914, 94–100.

Huber 1906

Karl Huber, Thuner Majolika, in: Illustriertes Fremdenblatt von Thun und Umgebung, 1906, 258–259, 278-279, 294–296.

Matteotti 1994

René Matteotti, Die Alte Landvogtei in Riehen (Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Basel 9), Basel 1994.

Merz 1874

Joseph Merz, Die Industrien im Berneroberland, deren Hebung und Vermehrung: Vortrag an der Hauptversammlung des gemeinnützigen Vereins des Kantons Bern, den 19. Oktober 1873 in Thun, Bern 1874.

Messerli Bolliger 1991

Barbara E. Messerli Bolliger, Der dekorative Entwurf in der Schweizer Keramik im 19. Jahrhundert, zwei Beispiele: Das Töpfereigebiet Heimberg-Steffisburg-Thun und die Tonwarenfabrik Ziegler in Schaffhausen, in: Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt 106, 1991, 5–100.

Messerli Bolliger 1993

Barbara E. Messerli Bolliger, Keramik in der Schweiz. Von den Anfängen bis heute, Zürich 1993.

Meyer-Heisig 1955

Erich Meyer-Heisig, Deutsche Bauerntöpferei. Geschichte und landschaftliche Gliederung, München 1955.

Riviale 2001

Pascal Riviale, Eugène Boban ou les aventures d’un antiquaire au pays des américanistes, in: Journal de la Société des Americanistes 87, 2001, 351–362.

Rohrbach 1999

Lewis Bunker Rohrbach, Men of Bern: The 1798 Bürgerverzeichnisse of Canton Bern, Switzerland, Rockport 1999.

Roth-Rubi/Schnyder/Egger u.a. 2000

Kathrin und Ernst Roth-Rubi/Rudolf Schnyder/Heinz und Kristina Egger u.a., Chacheli us em Bode… Der Kellerfund im Haus 315 in Nidfluh, Därstetten – ein Händlerdepot, Wimmis 2000.

Schwab 1921

Fernand Schwab, Beitrag zur Geschichte der bernischen Geschirrindustrie (Schweizer Industrie- und Handelsstudien 7), Weinfelden/Konstanz 1921.

Spies 1964

Gerd Spies, Hafner und Hafnerhandwerk in Südwestdeutschland (Volksleben 2), Tübingen 1964.

Wyss 1966

Robert L. Wyss, Berner Bauernkeramik (Berner Heimatbücher 100-103), Bern 1966.