Andreas Heege 2019

Transfer-printed decoration in CERAMICA CH

From a technological perspective this was a printing process where engraved copper plates were inked with a finely ground mixture of linseed oil and glaze, heated up and then printed onto a sheet of paper (hot press printing). The paper could then be cut into shape and placed on the pottery which had already been glazed. The design was then rubbed on and the colour transferred from the soft, wet paper to the vessel surface. Glue bat printing was a similar process, except that thin sheets of gelatine (bats) were used instead of paper. The engraved copper plate was rubbed with linseed oil and then wiped clean, leaving oil only in the lines of the engraving, which were then printed onto the gelatine. The gelatine was placed on the glazed vessel, transferring the oil, which was then dusted with finely ground glaze powder. The powder adhered to the oiled areas and was then fixed by a third firing.

Transfer-printing was developed in England in c. 1751, initially as overglaze decoration in black or red on faience and soft-paste porcelain (Maire 2008, 349). Attempts made in Italy (Turin and Doccia) during the first half and middle of the 18th century to use the same technique on faience and porcelain had proved commercially unsuccessful and not been pursued further (Mallett 2011).

Overglaze transfer printing on faience and stoneware was soon advertised throughout mainland Europe and used occasionally in the second half of the 18th century (Drakard/Holdway 1983, 10–17; Kronberger-Frentzen 1964, 9–28; Linnemann 1999, esp. 90 fn. 7; Decker/Hoffmann/Thevenin 1999, 76–80; Bolender/Beck-Coppola 2004; Maire 2008, 349–356; Bartels 1999, 245–246; Cluett 2004, 30). In Switzerland, for example, the Zurich Porcelain Manufactory began to use overglaze transfer printing as early as 1785 (decorations in black and purple) and its successor, the Nägeli factory, continued to use it (Bösch 2003, Vol. 1, 384, Vol. 2, 238-239; Ducret 2007, 33–34; Matter 2012, 99–100). From about 1780 onwards, English manufacturers began to replace overglaze decoration on refined white earthenware with transfer-printed decoration in blue and black under the glaze (Stellingwerf 2019, 46). Underglaze printed decoration in cobalt blue had, however, been used on English porcelain since the late 1750s.

In France and the rest of mainland Europe, transfer-printed refined white earthenware was not produced on a significant scale until after 1800 (Bolender/Beck-Coppola 2004, 37–63; Maire 2008, 349–420; Anglo-American production: Majewski/O’Brien 1987, 141–146). In Carouge near Geneva, transfer printing was used as early as between 1813 and 1819 (Strobino 2002, 8). By contrast, it does not appear to have been adopted in Montereau until 1818, and in Septfontaines until 1823/1824; its earliest use in Creil can be dated to 1827; in Wallerfangen and Mettlach it was used from 1825 (following early experiments with overglaze decoration in 1815), in Sarreguemines from around 1828/1830, in Longwy, Lorraine from around 1835; in Niderviller, the technique does not appear to have been added to the repertoire until c. 1850 (Decker 2003, 155; Maire 2008, 368–372; Decker/Thévenin 1992, 33; Adler 1991, 20; Desens 1998, 44–46; Thomas 1976, 23, 29, 37; Thomas 1977, 22; Linnemann 1999, 92–93; Bolender/Beck-Coppola 2004, 73–81). The same can be said for Maastricht, where transfer-printing was not used until 1844 (Bartels 1999, 246). Vessels with transfer-printed images were produced from 1830 in Damm near Aschaffenburg, from 1837 at Aschach Castle, district of Bad Kissingen, and from 1842 in Wächtersbach (Linnemann 1999, 92; Brandl 1993, 29–30; Wurzel 2001, 10; Linnemann 2001, 23-31). Around the same time, manufacturers in southern Germany, in Zell am Harmersbach, Hornberg and Schramberg began to produce vessels that were inspired by English and French examples. The introduction of transfer printing in those areas cannot be dated precisely, but it would not have been long after their French counterparts had begun to use the technique (Kronberger-Frentzen 1964; Simmermacher 2002, 63; Sandfuchs 1989, 10–13). The same applies to transfer-printed wares from the refined earthenware factories in the Upper Palatinate in Germany (Endres/Berwing-Wittl/Kleindorfer-Marx 2004, 35 Fig. 34 and 91–92). After 1846, transfer printing, mainly in black, blue and brown, and rarely green or bichrome, was also added to the range of refined earthenware production at Kilchberg-Schooren near Zurich (Ducret 2007).

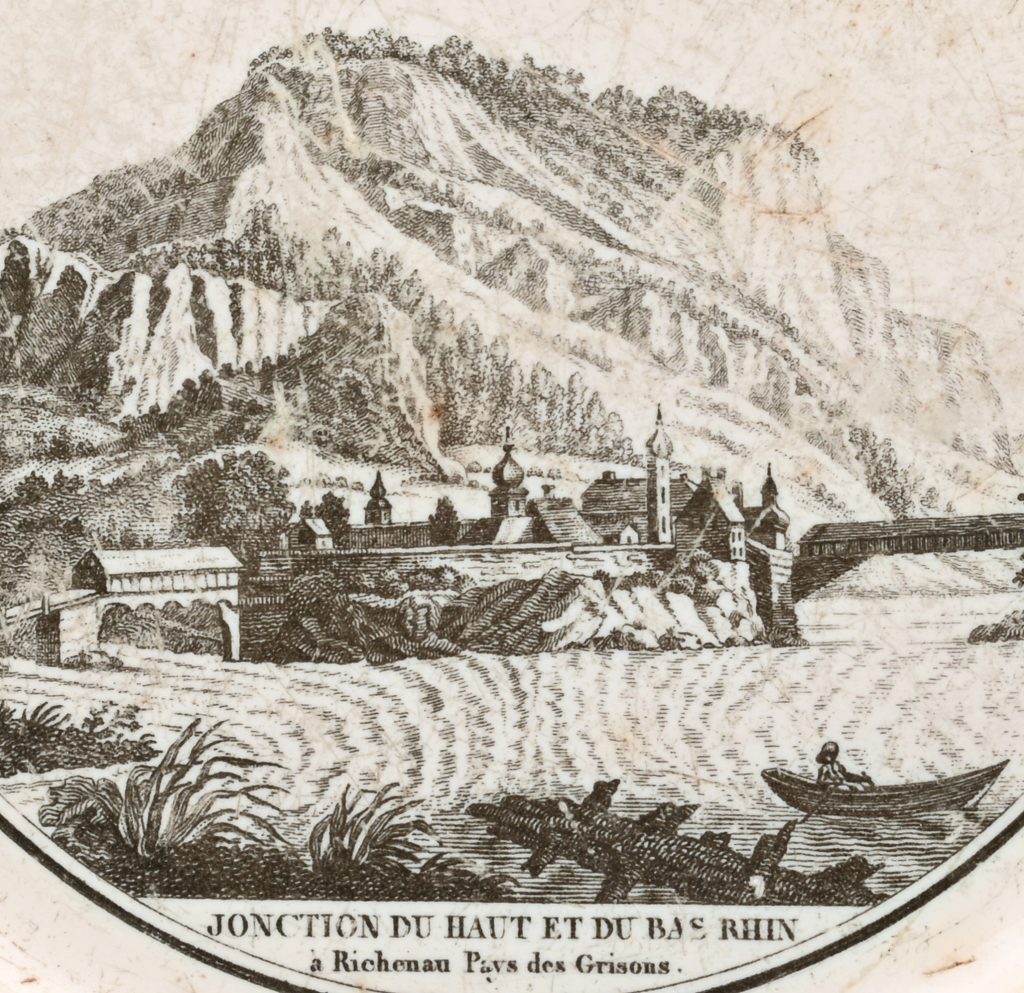

Line-engraving/hatching (French transfer-printed decoration, STONE factory, COQUEREL ET LE GROS, Creil, c. 1810/1820).

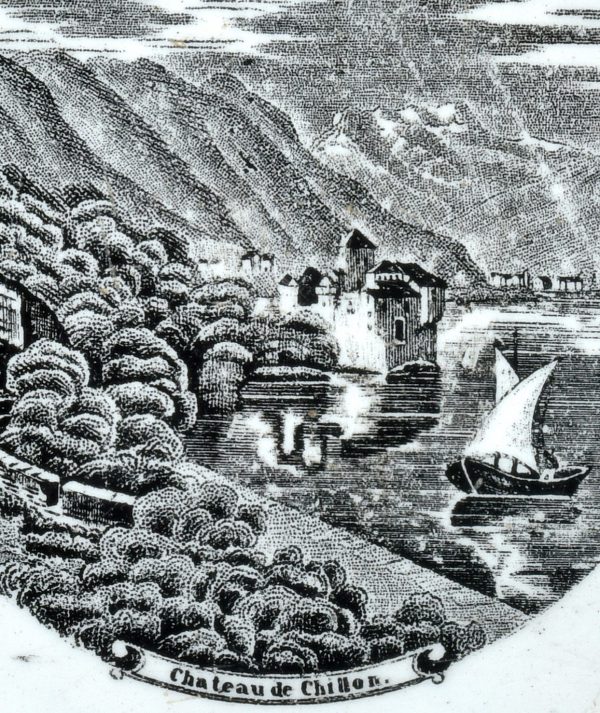

Design consisting of dots or stipples (stippling), transfer-printed decoration from the Johannes Scheller manufactory, Kilchberg-Schooren, c. 1850/1860

From around 1807, English manufacturers ceased to line-engrave (hatching) the printing plates and began to use designs that were made up of dots. Known as “stippling”, the technique allowed engravers to create more differentiated depictions and shading (Brooks 2005, 43; Bolender/Beck-Coppola 2004, 91; Bartels 1999, 245-246). On the Continent, however, both techniques continued to be used, sometimes side by side.

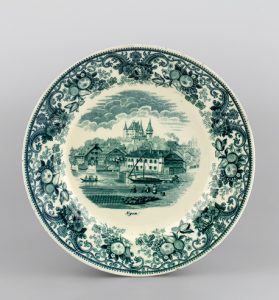

Over the course of the 19th century, the refined white earthenware industry developed new colours for use in underglaze transfer printing (“fancy colours”: green – from 1822; pink, purple, brown, and a deep, flowing blue – from the early 1830s). They were available either singly or in polychrome designs (underglaze printing in multiple colours), whereby a separate printing plate was used for each colour. From the 1830s onwards it was also possible to print up to three colours using only one plate (single-plate multicolour printing). This, however, required elaborate preparation because the different colours had to be rubbed onto the correct areas of the printing plate. It was not long after that, between c. 1835 and 1845, that polychrome colour printing using several printing plates was developed and perfected (multiple-plate multicolour printing). The engraver had to deconstruct the image into its colour components, which resulted initially in three or four, and by the 1850s and 60s, up to five or six printing plates being used. Each colour was printed onto paper, transferred onto the biscuit-fired vessel and then reheated to harden the colour and drive off the oil before adding the next colour. The final stage was to glaze the vessel and then fix the glaze by glost firing.

Particularly at the onset of historicism, transfer printing was sometimes enhanced by hand-painted designs or gilding (Linnemann 2001, 31). From the mid-19th century onwards, underglaze transfer-printing was gradually replaced by colourful overglaze-printing, i.e. by polychrome lithographs or chromolithographs (see Lithographic overglaze printing), although transfer-printing still continued to be used occasionally in refined white earthenware production. By the late 20th century, polychrome underglaze printed decoration (offset printing?) was also used, for instance, at the Langenthal porcelain factory.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

German: Umdruckdekor

French: décor imprimé

References:

Adler 1991

Beatrix Adler, 200 Jahre Keramiktradition Vaudrevange/Wallerfangen 1791-1991, Mettlach 1991.

Bartels 1999

Michiel Bartels, Steden in Scherven, Zwolle 1999.

Blondel 2001

Nicole Blondel, Céramique : vocabulaire technique, Paris 2001, 322-323 et 367-369.

Bolender/Beck-Coppola 2004

Charles J. Bolender/Martine Beck-Coppola, Les assiettes imprimées de Sarreguemines 1828-1838: La période Utzschneider, Paris 2004.

Bösch 2003

Franz Bösch, Zürcher Porzellanmanufaktur 1763-1790, Porzellan und Fayence, Bd. 1 und 2, Zürich 2003.

Brandl 1993

Andrea Brandl, Aschacher Steingut. Die Steingutfabrik (1829-1861) des Schweinfurter Industriellen Wilhelm Sattler (Schweinfurter Museumsschriften 55), Schweinfurt 1993.

Brooks 2005

Alasdair Brooks, An Archaeological Guide to British Ceramics in Australia, 1788-1901, Sydney 2005.

Cluett 2004

Robert E. Cluett, Staffordshire pottery 1858-1962. Majolica, transfer prints, flow blue, fine bone China from Cauldon, Atglen, PA 2004.

Decker 2003

Emile Decker, Une imagerie sur faïence : les assiettes parlantes à sujets imprimés de la manufacture de Sarreguemines, in : Jean-Michel Minovez, Faïence fine et porcelaine. Les hommes, les objets, les lieux, les techniques, Toulouse 2003, 153-170.

Decker/Thévenin 1992

Emile Decker/Christian Thévenin, Faïences de Sarreguemines. Les arts de la table (Collection Céramique), Nancy 1992.

Decker/Hoffmann/Thevenin 1999

Emile Decker/Diana Hoffmann/Christian Thevenin, Des hommes, des terres, des machines. La production de la faïence à la manufacture de Sarreguemines, Sarreguemines 1999.

Desens 1998

Rainer Desens, Villeroy & Boch. Ein Vierteljahrtausend europäische Industriegeschichte 1748-1998, Mettlach 1998.

Drakard/Holdway 1983

David Drakard/Paul Holdway, Spode printed ware, London 1983.

Ducret 2007

Peter Ducret, Bedrucktes Steingut aus der Manufaktur Scheller in Kilchberg, in: Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz, Mitteilungsblatt Nr. 119/120, 2007.

Endres/Berwing-Wittl/Kleindorfer-Marx 2004

Werner Endres/Margit Berwing-Wittl/Bärbel Kleindorfer-Marx, Steingut. Geschirr aus der Oberpfalz, München 2004.

Kronberger-Frentzen 1964

Hanna Kronberger-Frentzen, Altes Bildergeschirr. Bilderdruck auf Steingut aus süddeutschen und saarländischcen Manufakturen, Tübingen 1964.

Linnemann 1999

Blanka Linnemann, Bildergeschirr. Aspekte einer halbindustriellen Massenware des 19. Jahrhunderts am Beispiel Villeroy&Boch, in: Bärbel Kerkhoff-Hader/Werner Endres (Hrsg.), Keramische Produktion zwischen Handwerk und Industrie, Alltag – Souvenir – Technik, Beiträge zum 31. Internationalen Hafnerei – Symposion des Arbeitskreises für Keramikforschung in Bamberg vom 28. September bis 4. Oktober 1998 (Bamberger Beiträge zur Volkskunde 7), Hildburghausen 1999, 89-100.

Linnemann 2001

Blanka Linnemann, Vom einfarbigen Kupferdruck zum polychromen Steindruck, in: Thomas Wurzel, Wächtersbacher Steingut. Die Sammlung der Sparkassen-Kulturstiftung Hessen-Thüringen

Frankfurt 2001, 23-31.

Maire 2008

Christian Maire, Histoire de la faïence fine francaise 1743-1843, Le Mans 2008.

Majewski/O´Brien 1987

Teresita Majewski/Michael O´Brien, The use and misuse of nineteenth-century english and american ceramics in archaeological analysis, in: Michael B. Schiffer, Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory, Bd. 11, 1987, 97-209.

Mallett 2011

Mallet, John, Transfer printing in Italy and England. Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 22, 2011, 89-115.

Matter 2012

Annamaria Matter, Die archäologische Untersuchung in der ehemaligen Porzellanmanufaktur Kilchberg-Schooren. Keramikproduktion am linken Zürichseeufer 1763-1906 (Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 43), Zürich 2012.

Sandfuchs 1989

Bertram Sandfuchs, Zeller Keramik seit 1794: Ausstellung “Zeller Keramik” zum 850jährigen Stadtjubiläum, 7. Mai – 17. Septemberg 1989, Zell 1989.

Simmermacher 2002

René Simmermacher, Gebrauchskeramik in Südbaden, Karlsruhe 2002.

Stellingwerf 2019

Wytze Stellingwerf, The Patriot behind the pot. A historical and archaeological study of ceramics, glassware and politics in the Dutch household of the Revolutionary Era: 1780-1815, Zwolle 2019.

Strobino 2002

Georgette Strobino, Faïence fine du Léman au XIXe siècle: Carouge, Nyon, Sciez (Carnet du Musée de Carouge 3), Carouge 2002.

Thomas 1976

Thérèse Thomas, Villeroy & Boch. Keramik vom Barock bis zur Neuen Sachlichkeit. Ausstellung im Münchner Stadtmuseum, Mettlach 1976.

Thomas 1977

Thérèse Thomas, Villeroy&Boch 1748-1930. Keramik aus der Produktion zweier Jahrhunderte, Amsterdam 1977.

Wurzel 2001

Thomas Wurzel, Wächtersbacher Steingut. Die Sammlung der Sparkassen-Kulturstiftung Hessen-Thüringen, Frankfurt 2001.