Pottery from the region around Lake Geneva/Savoy in CERAMICA CH

Roland Blaettler, 2019 (with additions by Andreas Heege, 2023)

In compiling this inventory, we paid particular attention to the pottery that was commonly used in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, mainly slipped and glazed earthenware (MHL AA.46.D.21). It goes without saying that it is often difficult to interpret this type of product, as the vessel shapes and the techniques used to make them were very simple, widespread and long-lived. The frequent lack of decoration and the almost systematic absence of makers’ marks did not make our task any easier. We also realised that this type of everyday ware is not very well represented in museum collections. Objects of this kind rarely survived the passage of time, for the very reason that they were used every day and because their mundane appearance rarely triggered a conservation reflex.

We expected local history museums in rural areas, which are often dedicated to everyday life, to be more interested in this type of crockery. This, however, was not the case, neither in the Canton of Vaud, nor in the Canton of Neuchâtel. However, these museums tend to be more recent in date than urban museums and have generally been open only since the second half of the 20th century. In these relatively recent collections, it is just a small number of objects – within our area of interest – that came from local families; many more were acquired from antique dealers or were donated by collectors, which further blurred the exact provenance of the pottery

Against this background, it is not surprising that the everyday ware that has survived dates from no earlier than the late 19th century and more often than not from the first decades of the 20th century

Earlier specimens are rarely found (e. g. MHL AA.46.D.18; MHL AA.46.D.6; MVVE 5244; MPE Nr. 12; MHV 984; MHPN MH-FA-611; MHPN MH-FA-4061; MHPN MH-FA-525). But even in this recent segment our finds were not particularly abundant, neither with regard to everyday crockery, nor in terms of pottery which in contemporary sources was identified as “artistic” but was often created in the same workshops. This is rather surprising, given the number of pottery workshops we have inventoried so far, and for how long some of them remained in operation.

Having examined the collections in the Cantons of Neuchâtel and Vaud and comparing them with Genevan inventories (in particular with the Amoudruz collection at the Musée d’ethnographie), it became very clear to us that the everyday pottery within this rather vast region extending from the shores of Lake Geneva to the Neuchâtel Jura and Savoy (Buttin/Pachoud-Chevrier 2007) was very homogenous indeed.

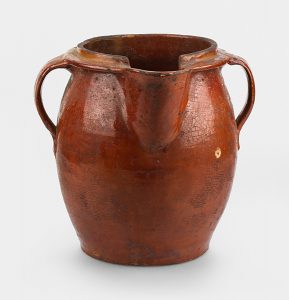

Examples are this cylindrical container for conserving foodstuffs, known in the Geneva region as “toupine” (MPE 2938; MVB 380B; MVB 380C; MVB 380D; MHPN MH-FA-4427A; MHPN MH-1996-79; MHPN MH-FA-4427B);

or this well-known type of jug with its tubular spout and double handles, usually coated in a green glaze (MM 920; MM 929; MHPN MH-1996-77).

Other examples are conical creaming bowls (MM 1014; MHPN MH-1996-78), including one of the few marked pieces from the “Poterie moderne” at Chavannes-près-Renens (MHL AA.46.D.22).

Yet others that are less often represented in the collections but are part of the same type of production include these cups and saucers (MVM M 193; MVM M 195), Daubières/braising pans (MHL AA.VL 90 C 690; MVB No 2) and lard pots (two handled jars: MVM M 204; MVM M 203).

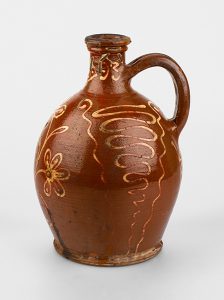

The same study area yielded numerous examples of another vessel which can be associated with the same type of production but is characterised by an almost systematic presence of decoration, usually consisting of sketched floral motifs or geometric patterns. This relatively homogenous group of objects is almost exclusively made up of cylindrical milk jugs in various sizes characterised by a thickened rim that is concave on the outside (MVB No. 1; MVVE 3210; MPE No. 8; MRVT No. 68; MRVT BR 4a; MRVT No. 67; MRVT BR 4; MPA 914; MPA Bv 4; MPA Bv 15; MPA Bv 12; MPA Bv 5).

An illustration in an anthropological study (De Freire de Andrade and De Chastonay 1956, Fig. 5) and numerous similar examples in the Amoudruz collection of the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève (Anthropological Museum in Geneva), which are almost all attributed to “Colovrex”, initially led us to assume that they originated from the Knecht potteries in Colovrex (or even in Ferney-Voltaire). The Amoudruz collection also contains a series of pots of the same shape with commemorative inscriptions dating them to between 1914 and 1967. The more objects we examined, however, the more we identified differences in how they were made. While these differences could be explained partially by the fact that the type remained in use for a long time, they actually suggested that other workshops had been producing very similar types. And so it turned out to be; when examining material from the Canton of Neuchâtel, we recently found a small cylindrical milk jug in the collection of the Musée régional du Val-de-Travers in Môtiers, which perfectly matches the category and which had not been included in the first volume of the printed version of our inventory (Ceramica CH, vol. I). However, the vessel, which is decorated with a polychrome marbled pattern on a dark-brown background, bears the stamped mark of the “Poterie modern” at Chavannes-près-Renens (MRVT No. 26)!

At the time, we had not yet identified this mark, but we now know that it was introduced in 1902, just after Lucien Ménétrey had founded the company. It remained in use probably until 1905 when the business was reregistered as a public limited company (see “Renens, Canton of Vaud, the potteries”). It is thanks to this vessel, which to our knowledge is the only one of this type that bears a mark, we now know that cylindrical jugs of this kind cannot be automatically attributed to the Knecht workshops.

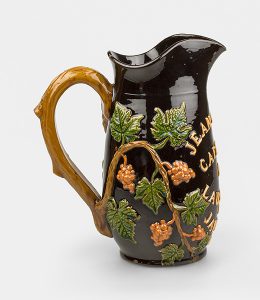

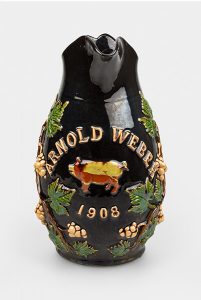

It is obvious, however, that the Knechts and their enterprises on either side of the border played an important role in the development of slipped earthenware in the region of Lake Geneva. In the period between 1875 and 1920, their range included an elaborately decorated type of pottery that could be classed as “artistic”: the famous patronymic jugs (also known as “welcoming jugs”, particularly in the literature on Ferney) with moulded applied decorations in the shape of vine branches (MVVE 2355; MVVE 2411).

Thanks to only two known marked specimens, both in the collection of the Musée du Château de Nyon (Historical and Porcelain Museum, Nyon Castle) (MHPN MH-2015-9; MHPN MH-2014-10), this type of jug can be firmly attributed today to the Knecht potteries. As far as we can tell so far, these jugs were distributed over a similar area to that of the cylindrical jugs with sketched or geometric floral patterns, i.e. the Cantons of Geneva, Vaud and Neuchâtel (see above). “Welcoming jugs” therefore serve as an indicator of the abundance of Knecht wares in an area that extended far beyond the borders of the Canton of Geneva. We can assume that the same applied to the everyday crockery.

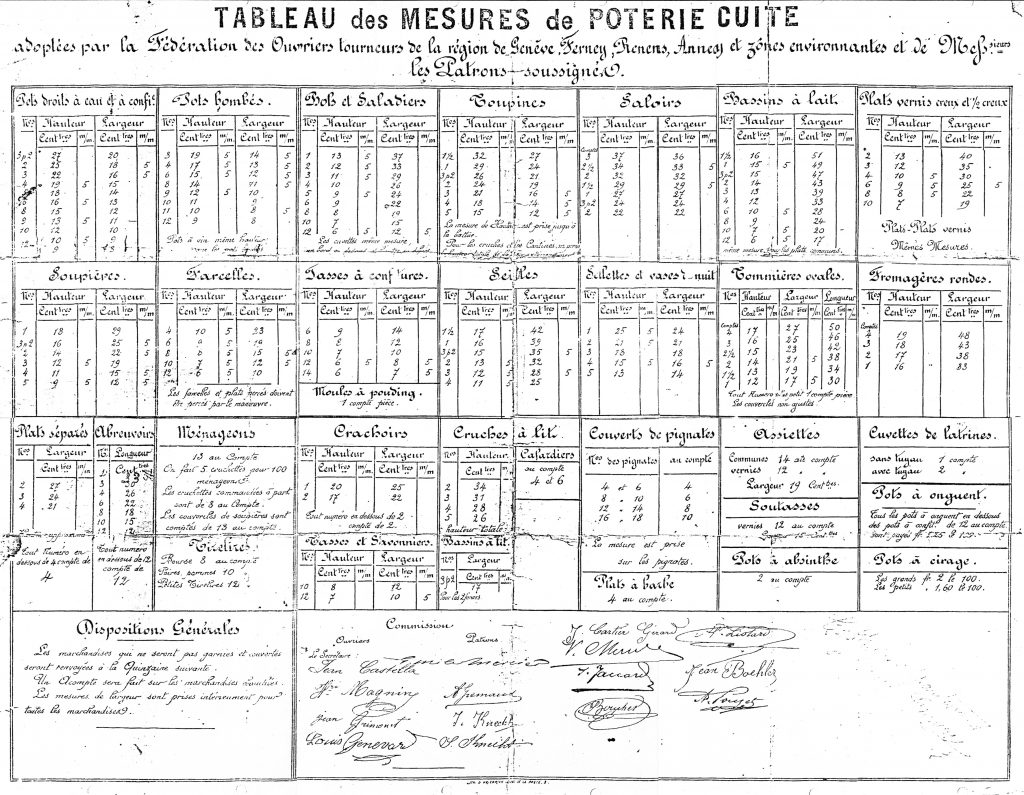

Size chart for pottery adopted by the Federation of Potters in the regions of Geneva, Ferney, Renens, Annecy and the surrounding areas and by the undersigned employers.

Because it has not been possible to attribute the everyday wares from the Cantons of Neuchâtel and Vaud to any particular workshop, particularly the undecorated ones, we have decided to combine them all under the umbrella term “slipped earthenware from the Lake Geneva region” for now. This approach is supported by a document published in 1984 by a group of historians from Ferney-Voltaire: the “Tableau des mesures de poterie cuite adoptées par la Fédération des ouvriers tourneurs de la région de Genève, Ferney, Renens, Annecy et zones environnantes et de Messieurs les patrons soussignés” [Size chart for pottery adopted by the Federation of Potters from the region of Geneva, Ferney, Renens, Annecy and the surrounding areas and by the undersigned employers] (Ferney-Voltaire 1984, 264–265).

This lithograph from the late 19th century (we would suggest a date of between 1893 and 1896) was intended for display on workshop walls. It attests to the efforts made by the master potters from the Lake Geneva region to coordinate pricing, possibly in response to pressure from the Association of Throwers (Fédération des ouvriers tourneurs). The table lists the number of pieces of each shape a potter had to be able to create from a specific amount of clay known as a “compte”. The “compte” therefore served as a unit to determine how much a thrower was owed.

The table contains approximately 30 shapes in various sizes with height and width measurements accurate to half a centimetre. The specificity of the measurements suggests that the shapes were rather strictly standardised.

The document suggests that there was a cross-border group of experts which brought together the employees on the one hand and the employers on the other. The fact that this syndicate existed was obviously due to the high permeability of the border in terms of the mobility of skilled workers. It is obvious that throwers, for instance, had to be able to move from one workshop to the next even if it meant crossing the border. The history of the different workshops in Nyon or Renens clearly shows close personal relationships between some of these workshops and the pottery centre at Ferney-Voltaire which existed into the early 20th century (see especially the chapters «Nyon VD, La Poterie commune und ihre Nachfolger, Richard Frères» und «Renens VD, die Töpfereien»).

The signatures of the employers at the bottom of the document included that of master potter Alexandre Liotard, who had worked in Ferney-Voltaire since 1882. The Knecht potteries in Colovrex and Ferney-Voltaire were represented by the signature of Stanislas Knecht. After Lucien Knecht’s death in 1890, both workshops were taken over by his widow Jeanne and their three sons Stanislas, Arnold and Louis (Buttin/Pachoud-Chevrier 2007, 85-88). Below Stanislas Kencht’s signature is that of Jean Bœhler, who managed the Poterie commune de Nyon from 1885 to 1902. The potters from Renens are all listed: Samuel Jaccard, resident in Renens since 1890, Paul Bouchet, who took over the workshop his father had set up in 1883, and Émile Mercier, who founded his workshop in 1892 and remained at the helm of the company until 1898. The employers’ group also included four Genevan potters, Aimé Joseph Amédée Gremaud, a potter and stove fitter, who was resident at Place de la Navigation square from 1883 to 1899 (SOGC, vol. 1, 1883, 723 – Vol. 17, 1899, 1241); Alfred Pouzet, who in 1888 took over the workshop his father Antoine had founded on Rue de la Terrassière four years previously and ran it until 1924 (SOGC, vol. 6, 1888, 716 – 42, 1924, 734); Jacob Knecht, a nephew of Henry, founding father of the Ferney pottery, who had trained alongside his uncle before taking over a workshop on Rue du Temple in Carouge in 1884 (SOGC, vol. 2, 1884, 45), and finally François-Joseph Cartier-Girard, owner of a “pottery factory for utility ware”, which he had established in Petit-Saconnex (Canton of Geneva) in 1893 and which he ran until his premature death in 1896 (SOGC, vol. 11, 1893, 195 – vol. 14, 1896, 1097). Incidentally, the pottery factory was taken over in 1896 by Louis-Charles Leuba, Jules Genoux and Henri Magnin and named Leuba et Co. (SOGC, vol. 14, 1896, 1089). The National Museum in Zurich has in its collection a water jug for serving absinthe that bears the mark “G. Girard Genève” (Inv. LM-65630).

Henri Magnin is also among the undersigned, though on the side of the workers. At the time he was president of the Chambre syndicale des ouvriers tourneurs en poterie du canton de Genève (Association of potters in the Canton of Geneva), which had been established in 1892. He remained in office until at least 1901 (SOGC, vol. 10, 1892, 934 – vol. 19, 1901, 782). A few years later, between 1905 and 1907, Henri Magnin became director of the Poterie moderne S. A. at Chavannes-près-Renens (see the chapter “Chavannes-près-Renens VD, Poterie moderne (S.A.), 1902-1972/73»).

As this document shows, the potters in the Lake Geneva region and in parts of Savoy (Buttin/Pachoud-Chevrier 2007) maintained a genuine network, at the levels of both the employers and the employees. It should therefore come as no surprise that their basic wares – undecorated everyday crockery and items of everyday use as produced by most workshops – formed an homogenous whole.

To return to the stylised or geometric floral patterns on the cylindrical milk jugs mentioned above, we have occasionally come across very similar ornaments and type of make in other shapes: milk jugs (MVB 380F; MVB 380E; MPA Bc 32), a plate in the collection of the Musée du Pays-d’Enhaut in Château-d’Œx [Museum of the Old-Pays d’Enhaut] (MPE 1336) and another plate in the Museum of Montreux (MM 766). The similarities between the floral patterns on these vessels and the ones on the cylindrical jugs is particularly obvious on a plate that may have been made by the Poterie commune de Nyon when it was still being run by Théophile Thomas-Morello (MPE 2995). It should be noted that these few objects are the only ones that have come to light so far where this type of decoration appears on a shape other than a cylindrical jug. In the Amoudruz collection, only about ten plates or milk jugs among a total of around 400 regional ceramic objects bear a similar decoration

As can be seen in a photograph of Jacob Knecht’s stand at the Exposition industrielle de Carouge-Acacias in 1906, his pottery workshop in Carouge produced crockery that bore similar decorations as the ubiquitous vessels described above (Dumaret 2006, 141–143, Fig. 113).

Jacob Knecht’s son Édouard (1876–1928) succeeded him as company director in 1913 (SOGC, vol. 32, 1914, 1289). After Édouard’s death, the business was run by his widow Lina and renamed Veuve Édouard Knecht; in 1930, Lina went into partnership with the sculptor Jean Chomel (1902–1979 – SOGC, vol. 48, 1930, 903) and named the new company Knecht & Chomel. When Lina died in 1932, Chomel continued to run the business on his own, until he founded the Poterie de Carouge S. A. in 1934. This company was declared bankrupt two years later (SOGC, vol. 52, 1934, 2101 – vol. 54, 1936, 1984).

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

Sources:

Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, from 1883 (accessed via the website e-periodica.ch)

References:

Buttin/Pachoud-Chevrier 2007

Anne Buttin/Michèle Pachoud-Chevrier, La Poterie domestique en Savoie, Annecy 2007.

De Freire de Andrade et de Chastonay 1956

Nadège de Freire de Andrade et de Philibert Chastonay, La dernière poterie rustique genevoise. Archives suisses d’anthropologie générale XXI, 8-141.

Dumaret 2006

Isabelle Dumaret, Faïenceries et faïenciers à Carouge. Arts à Carouge: Céramistes et figuristes. Dictionnaire carougeois IV A. Carouge 2006, 15-253.

Ferney-Voltaire 1984

Ferney-Voltaire. Pages d’histoire. Ferney-Voltaire/Annecy 1984.