C.A. Schmalz, 1949 self-portrait and photo of his early works.

Pottery made by Cäsar Adolf Schmalz in CERAMICA CH

Andreas Heege and Roland Blaettler, 2022

Cäsar Adolf Schmalz (1887, Stalden-Konolfingen – 1966, Heimberg) was one of 14 children. His father was employed as a surveyor for the land register, his mother ran the local post office (Schmalz family tree). Having completed his secondary school education in Grosshöchstetten, he attended a three-year course at the Museum of Applied Arts in Bern under the tutelage Paul Wyss, qualifying as a draughtsman. His final exam was adjudicated on by the Bernese graphic designer Rudolf Münger. As he said himself, Paul Wyss ignited “a holy fire” within him for the arts and for Heimberg pottery (Marti/Straubhaar 2017, 9). Because he spent a lot of his spare time drawing and making clay statues, he was encouraged to apply to the cantonal authorities of Bern for a grant, which was approved. In 1908, he travelled to Spain where he studied at the Prado museum and modelled animal and bullfighter figures for a porcelain manufacturer. He also spent a year in Paris, after which he returned home in 1910 and married Liseli Engel (originally from Bowil, 11/2/1887-18/4/1965) in Steffisburg on 28th June 1910 (announcement of the nuptials in the Tagblatt der Stadt Thun, Volume 34, No. 160, 9th July 1910). Up to the and possibly beyond the outbreak of the First World War he worked in Steffisburg. His autobiographical notes from 1952 read: “In Steffisburg I painted cups and plates, and modelled jugs, bowls and figures. This earned me an encouragement award and a few prizes at competitions.” Unfortunately, Schmalz is a little vague here, and there is no information in any of his other papers that would point to the workshop where he was employed. Based on three signed figures which were later found among his works, we can assume that he was employed at some point by Karl Loder-Eyer in Steffisburg.

A tour of the bazaar by a journalist from the NZZ newspaper (21/6/1914) specifically mentioned “jolly groups of dancing peasants” (ceramic figurines?) from the Loder-Eyer workshop, none of whom, to our knowledge, have survived.

We do know of a private collection that does, however, contain three signed figures with a reference to the homeware store “Kaiser & Cie” in Bern. It was also among the approved suppliers to the Swiss Heritage bazaar and had submitted numerous objects to the “souvenir competition” that had been held in advance of the National Exhibition. Surprisingly however, the 1913 list of awards does not identify Karl Loder- Eyer as the artist who made the figures, but rather the ceramicist Cäsar Adolf Schmalz from Heimberg (“12 figures of peasant dancers and musicians”). A monograph on Schmalz’s work also lists the figures (Marti/Straubhaar 2017, 127).

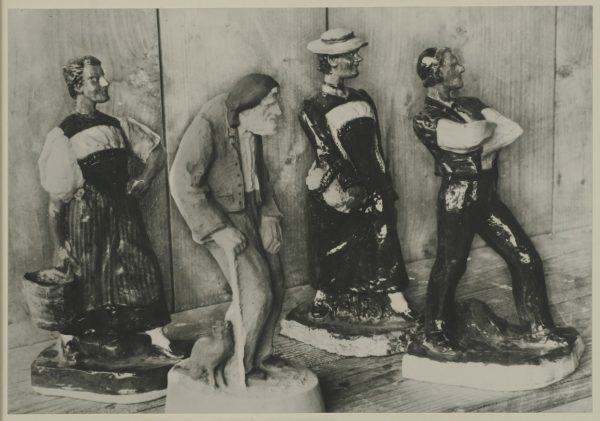

Other early works, including armorial plates, vases, bowls and historical or satirical figures or groups of figures are known from pictures taken by the Bernese photographer Hermann Stauder in 1917 (see also the image at the beginning).

Figures made by Cäsar Adolf Schmalz in 1917 (Stauder 1917).

From 1914 to 1918, Schmalz was called up for national defence duty with the Swiss Army. This, however, did not stop him from bringing his sketching pad wherever he went or offering his figures for sale (Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich 1916: Illustrierte schweizerische Handwerker-Zeitung : unabhängiges Geschäftsblatt der gesamten Meisterschaft aller Handwerke und Gewerbe, Volume 32, 1916, 400).

In 1921, Schmalz bought a small farm in Heimberg called “Rebeli” on the Aare River, set up a workshop and apparently continued his training as a self-taught ceramicist while looking after his small holding.

Figures from the period around 1922-1930.

In 1922, Schmalz exhibited several ceramic sculptures at the first national exhibition of applied arts staged by L’Œuvre in the hall of the Comptoir Suisse in Lausanne. The motifs were rural scenes (Cat. p. 47, Nos. 210–213). A year later, audiences in the Canton of Vaud were afforded another opportunity to see Schmalz’s ceramics in the second arts exhibition which was staged by the Société de développement de Montreux (Montreux tourist board) in the salons of the spa and ran from 25th March to 8th April. The exhibition was dedicated specifically to the contemporary arts scene in the German and Italian speaking parts of Switzerland (Feuille d’avis de Vevey dated 21st March 1923, 6 – Tribune de Lausanne dated 4th April, 3).

This may have been where the Federal Government acquired a small statue, which it later loaned to the Arts and crafts Museum in Lausanne (MHL AA.MI.1644).

Dish made by Cäsar Adolph Schmalz. The well bears the red and green coat of arms of the town of Moudon. “Fert” was the motto used by the former Italian Royal Dynasty of Savoy. On 22nd October 1931, a “Vente paroissiale” (parish sale) was held by the Parish of Moudon to raise funds for the restoration and upkeep of the Church of Saint-Étienne (L´Echo de la Broie, 10/10/1931,4). The dish was probably made especially for this occasion.

In 1931, Cäsar Adolf Schmalz accepted an offer for the position of instructor at the Swiss School of Ceramics in Chavannes-Renens (Chavannes-Renens, Swiss School of Ceramics). He was mentioned in the director’s graduation speech that year (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 4th April 1931, 24). Schmalz himself wrote: “The position pays well and for once, my financial worries have eased” (Marti and Straubhaar 2017, 13). However, the job was also very time-consuming and left very little opportunity for his own creative endeavours. It soon became obvious that the experiment was not going to last very long. Schmalz’s own commentary concerning his employment in Chavannes was somewhat contradictory: in one record he spoke about “two years”, another mentioned “three years” (Marti and Straubhaar 2017, 10 and 13). The fact that the school’s entry in the Indicateur vaudois (phone- and address book for the Canton of Vaud) only listed him in 1932 (with Fritz as his first name!), probably means that he was hired some time in 1931 and resigned from the post by the end of 1932 at the latest.

His artistic endeavours were severely curtailed again because of the Second World War. Most of his time was spent on serving in the military and looking after his farm. Later, he taught modelling classes at an adult education centre. He was a passionate angler and friend of the Emmentaler Jodler, a community yodelling group in Konolfingen. Cäsar Adolf Schmalz’s often playful creativity found its expression in many different fields, including painting, water-colours, illustration, mosaics, frescoes and, of course, pottery.

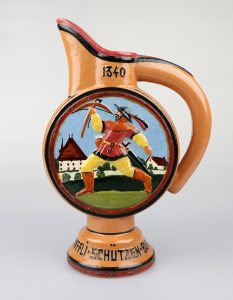

When creating ceramics, he mainly used the traditional Heimberg technique to make slipped and glazed earthenware. Sometimes historicist, sometimes modernist, all his works were very colourful. He was often commissioned to create souvenirs and prizes for shooting or choral societies as well as objects bearing family coats of arms for private individuals (Messerli 2017, 73-79; Marti/Straubhaar 2017,9).

“Die Bürgerwehr vom Wetterloch, 1950” [The Wetterloch Militia]. This piece was based on Karl Grunder’s dialect work “Ds Wätterloch. Bilder u. Begäbeheite us d. Mobilisationszeit vom Jahr 1914”, first published in Bern-Bümpliz in 1928. The Bernese dialect poet and teacher Karl Grunder (1880–1963) was a pioneer in rural theatre culture and member of the Berner Heimatschutztheater [a theatre company that came out of the 1914 National Exhibition and specialised in dialect plays].

His figures of prominent people in Bern’s history were very popular and thanks to his mastery of making plaster of Paris moulds, he was able to reproduce them multiple times (HMO 8342).

The Regional Museum in Langnau has four of Schmalz’s figures in its collection, including two depictions of Schultheiss (chief magistrate) Niklaus Friedrich von Steiger at the Battle of Grauholz, one of Elsi, the mysterious maidservant (see Marti/Straubhaar 2017, 221 on the story about the maidservant) and one of the eminent “Doctor of the Alps”, Michael Schüppach, (cf. also HMO 8342, BHzD 482 and Marti/Straubhaar 2017, 109–111).

Micheli Schüppach, “Doctor of the Alps”.

A figure group (HMO 7179) discovered at the Historical Museum in Olten shows that Schmalz did some work for the Langenthal Porcelain Factory during the early part of his career.

In addition to these colourful and rather playful products, Schmalz over time also began to produce a more academic and modernist type of ceramic sculpture consisting of monochrome figures of a more general nature (Amstutz 1931, Fig. pp. 53–54 and 57; F. A. 1966 – obituary in the Bund newspaper).

A website presents Cäsar Adolf Schmalz’s versatile artistic work.

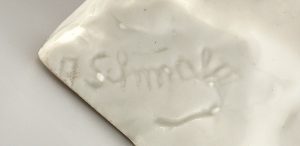

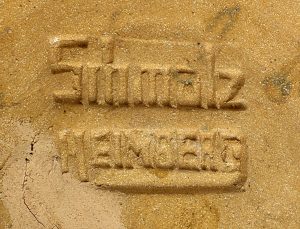

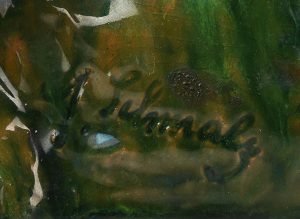

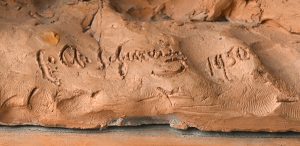

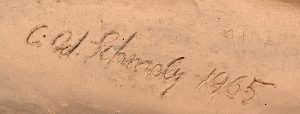

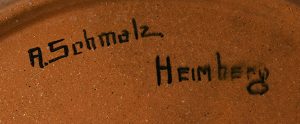

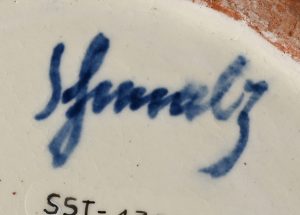

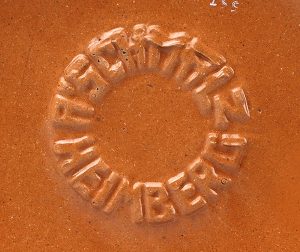

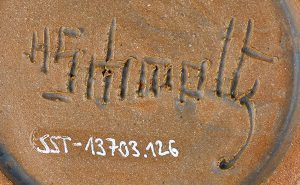

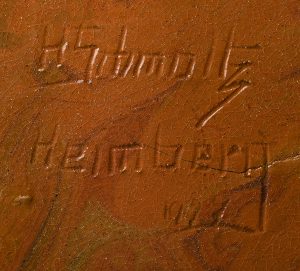

Die Marken und Signaturen von C.A. Schmalz

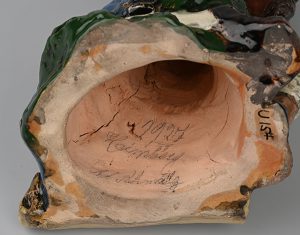

The earliest known mark is an impressed mark consisting of two lines stamped individually, the one on top reads “Schmalz”, the one below “HEIMBERG”. Only one work bearing this mark is dated precisely to the year 1926. It was probably used for all of Cäsar Adolf Schmalz’s “early works”. One piece is known where the “HEIMBERG” stamp was omitted.

A square impressed mark bearing C. A. Schmalz’s family coat of arms can be dated to 1943 and 1944.

Another impressed mark shows a proper escutcheon and the name “Schmalz”; it dates to the period between 1947 and 1957..

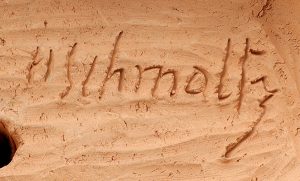

Schmalz also often used incised signatures. In 1928 and 1945 he just signed his name, Schmalz; in 1929 he used “A. Schmalz”; in 1950 “C. A. Schmalz” and in 1965 “C. Ad. Schmalz”. The initials “A. S.” are only known from one (undated) object.

Painted marks, however, are much rarer. One from 1931 reads “A. Schmalz Heimberg”; others, from 1935 and 1945, just read “Schmalz”.

Cast vessels dating from between 1936 and 1946 bear a circular moulded mark “A.SCHMALZ HEIMBERG”.

Hans Schmaltz (1910-1972)

Cäsar Adolf Schmalz and Liseli Engel had one son, Hans (1910-1972).

Pottery made by Hans Schmalz in CERAMICA CH

Hans also became a ceramicist, following in his father’s footsteps while working on the small family farm (obituary in the Thuner Tagblatt, 14th September 1972).

Signed and dated (1931) figure made by Hans Schmaltz. Was it made during his father’s employment at the Swiss School of Ceramics in Chavannes-Renens?

It is not known where Hans learnt his craft as a ceramicist (probably from his father, and perhaps during the latter’s employment at the Swiss School of Ceramics in Chavannes-Renens?).

Throughout his whole life, he distinguished himself from his father by spelling his surname “Schmaltz” instead of “Schmalz”.

Pottery made by Hans Schmaltz for various shooting festivals, 1931-1936.

Some dated and marked ceramics show that Hans produced works independent of his father, apparently from as early as 1931.

He received his first mention in the press in a report on his own works and his father’s in the BUND newspaper dated 4th December 1935.

Beetle figures made by Hans Schmaltz.

According to the report, Hans mainly produced bird and beetle figures in various sizes, as well as crockery and the usual souvenirs and plates for festivals and shooting clubs.

Bird and animal figures by Hans Schmaltz.

Musicians and a jester, figures by Hans Schmaltz.

The only time his figures were shown in an art exhibition was in 1938 at the Beau Rivage Hotel in Thun; they were very favourably reviewed (Oberländer Tagblatt 62, 19th November 1938; Der Bund 25th November 1938; Geschäftsblatt für den oberen Teil des Kantons Bern, Volume 85, No. 138, 25th November 1938).

Ceramic vessels by Hans Schmaltz.

After 1945, his ceramics were never again mentioned in the press. In 1949 and 1954, he produced bird figures for the exhibitions of the Sing- und Ziervogelverein Thun und Umgebung (Cage and Songbird Fanciers’ Society of Thun and Surroundings).

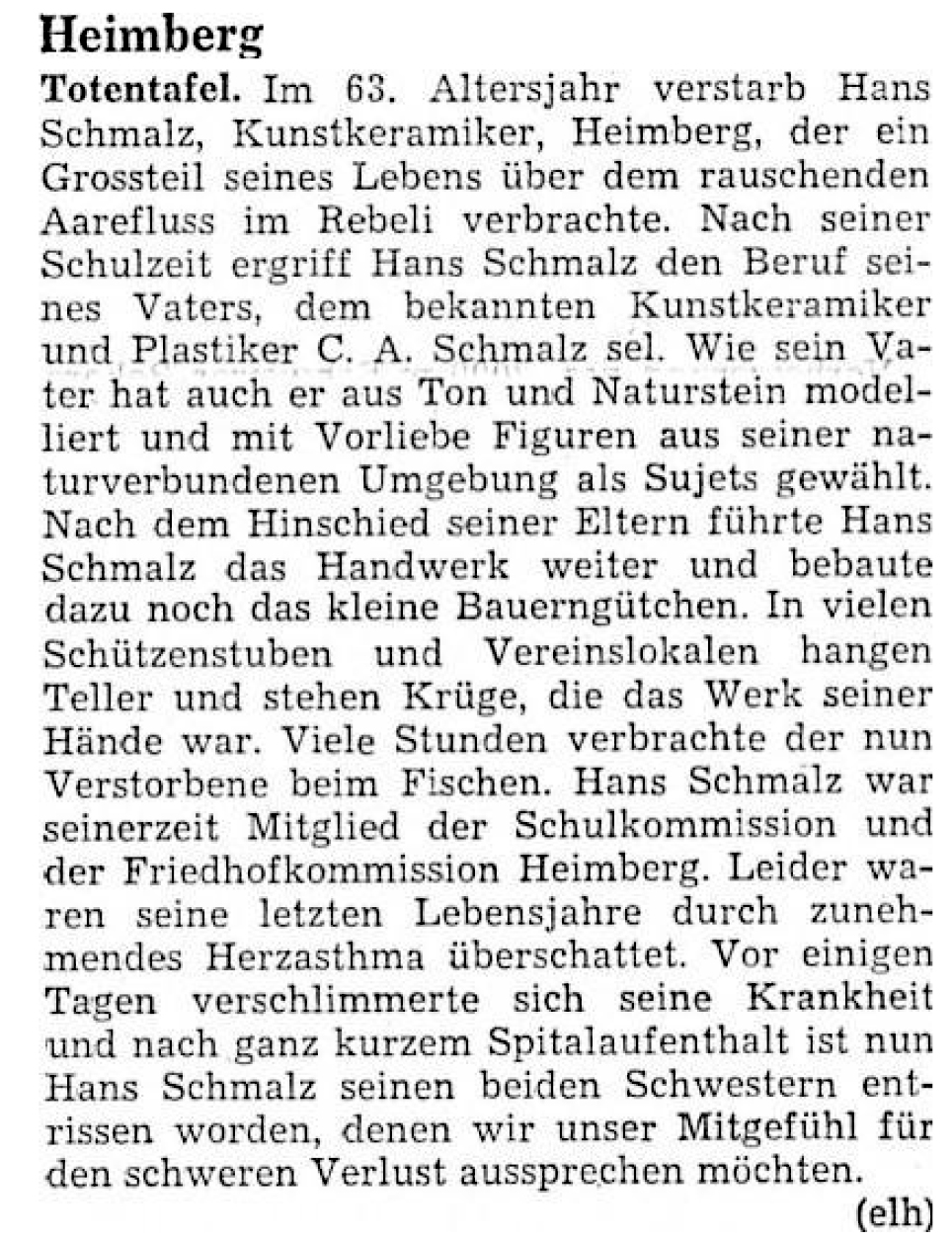

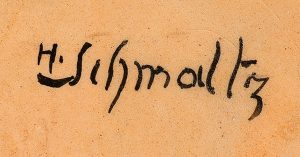

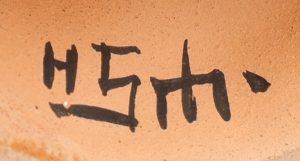

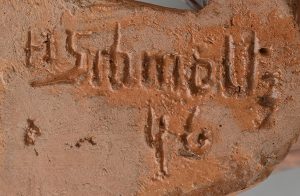

The marks and signatures used by Hans Schmaltz

Like his father, Hans Schmaltz used the two-part impressed mark (“Schmaltz” and “Heimberg”) on his early works. It has been found on three dated pieces from 1931, 1935 and 1936.

A signature “Schmaltz H” which was incised into the plaster of Paris mould and then appeared in relief on the ceramic object (moulded mark), has been found on two undated pieces.

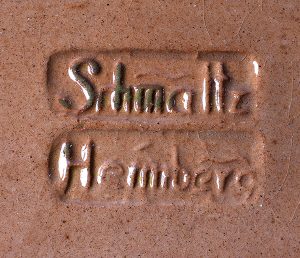

Otherwise, Hans used painted marks “H Schmaltz” or “H. Schmaltz” (painted mark), though none of those pieces are dated. An abbreviated signature “H Sch.” has been found on one (undated) piece.

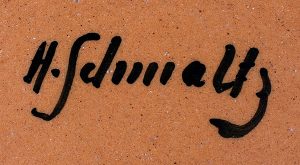

Incised signatures “H Schmaltz” (incised mark) occur more frequently and have been found on pieces from 1931, 1938, 1946 and 1947.

One piece bears a fish with an incised mark.

Incised marks “Schmaltz”, “Schmaltz Heimberg” and “H. Schmaltz-Heimberg” have all been found on undated pieces.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

References:

Amstutz 1931

Ulrich Amstutz, Der Plastiker Adolf Schmalz in Heimberg bei Thun, in: Historischer Kalender oder der Hinkende Bot 204, Bern 1931.

Blaettler/Schnyder 2014

Roland Blaettler/Rudolf Schnyder, CERAMICA CH II: Solothurn (Nationales Inventar der Keramik in den öffentlichen Sammlungen der Schweiz, 1500-1950), Sulgen 2014, 368.

FA 1966

FA, † Cäsar Adolf Schmalz. Der Bund, Abendausgabe 468, 30.11.1966, 4.

Marti/Straubhaar 2017

Erich Marti/Beat Straubhaar, C.A. Schmalz 1887-1966. Leben und Werk mit Pinsel, Stift und Lehm, Heimberg 2017.

Messerli 2017

Christoph Messerli, 100 Jahre Berner Keramik von der Thuner Majolika bis zum künstlerischen Werk von Margrit Linck-Daepp (1987-1983). Hochschulschrift (Datenträger CD-ROM), Bern 2017.

Stauder 1917

Hermann Stauder, Die Töpferei im Heimberg (Nachdruck des Kunst- und Kulturverein Heimberg, 1985, Original Schweizerische Landesbibliothek Bern), Bern 1917.