Remains of two earthenware kilns at the Staub workshop in Langenthal, Canton of Bern (photo by Andreas Heege, Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern)

The potter’s kiln (pottery kiln or just “kiln”) is the single most important piece of equipment for a potter or industrial producer of faience, refined white earthenware, stoneware or porcelain. It is therefore no surprise that every country in the world that produced its own pottery found different technological solutions to reach the desired firing temperatures or kiln atmospheres.

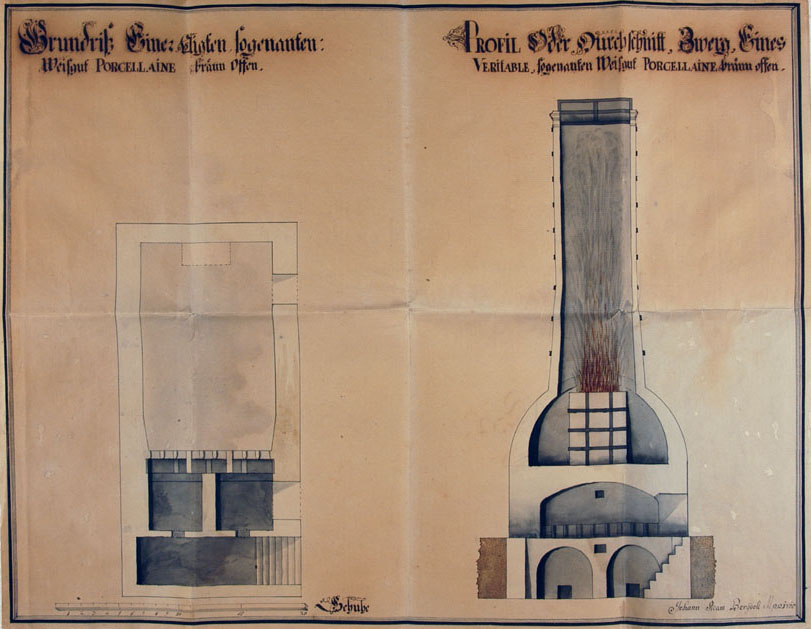

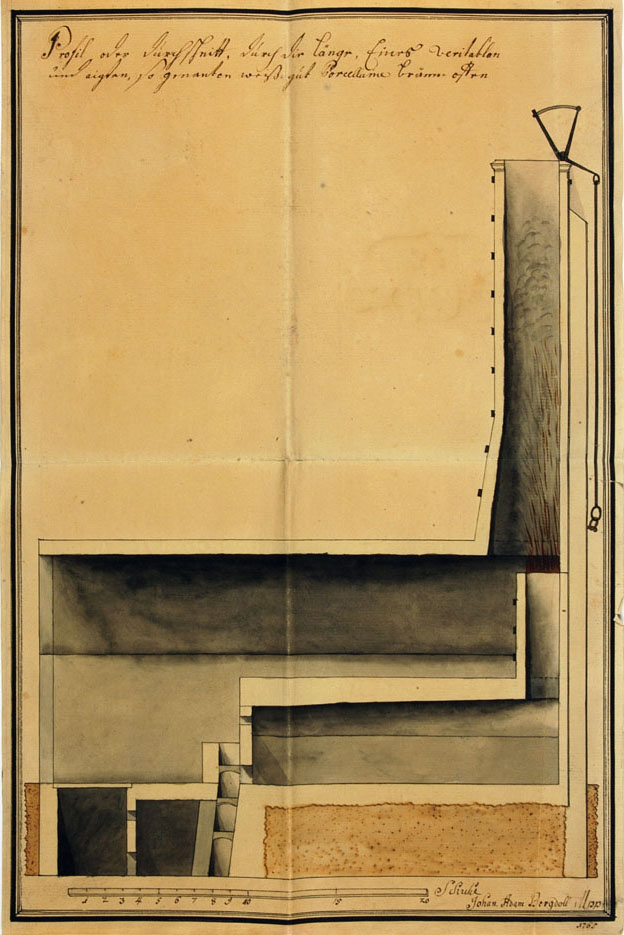

Sectional drawings of the porcelain kiln at the Frankental Manufactory from 1765 (photo BNM).

In Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and Switzerland, pottery kilns dating from the period between the 6th and 20th centuries are found quite regularly during archaeological excavations. Various research gaps and deficiencies exist with regard to the quality of the excavation records, the state of preservation of the kilns and their regional or chronological distribution. Very few kilns have survived intact, be it physically or even just in the form of historical plans. Most have been discovered and recorded by archaeologists. In the study area, this has amounted to more than 100 kilns being examined every decade since the end of the Second World War.

The number of known pottery kilns varies according to the size of each country. It is therefore no surprise that a large number have come to light in the Federal Republic of Germany. However, when studying their distribution across the individual states of Germany and Austria, the cantons of Switzerland, the regions of Belgium and the provinces of the Netherlands, it quickly becomes apparent that there are considerable regional differences. This is at least partially due to disparities regarding the specific research focus and approach taken by the individual archaeological institutions and other disciplines (e.g. folklife studies, European ethnology, heritage management).

Across all of the countries studied, there are considerable gaps in the chronological distribution of kiln features. There is a dearth of such features in the 10th and 11th centuries as well as the late 14th to early 16th centuries. The 18th and 19th centuries have not yielded a large number of features either, although this is offset slightly by plans from historical records and architectural surveys. The 6th to 8th centuries as well as the late 12th to early 14th centuries can be considered well researched. These gaps in our knowledge make it more difficult, or in some cases even impossible, to trace and reconstruct the technological lines of development. It also means that we can only speculate when it comes to identifying technological interactions between the potters in different regions. To gain a better understanding, particularly of the early western-European influence (horizontal kilns), it would be crucial to critically review the remains of pottery kilns in (northern) France.

While the existence of large centres or regions of pottery production tends to influence the number of kilns that have and continue to come to light, it does not necessarily follow that an area that once had a large number of workshops now has a comparable number of excavated or recorded remains of kilns (e.g. Brunssum-Schinveld, Netherlands, Siegburg, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, Westerwald, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, Saxon centres of stoneware production, Germany, Kröning in Bavaria, Germany etc.).

Two basic types of kiln can be identified from the remains that have been found so far:

1. Vertical kilns with a horizontal separation between the fireplace above and the firing chamber below by means of a suspended, perforated floor. These are updraught kilns, designed as domed kilns or top-loaders.

2. Horizontal kilns with a perforated vertical partition wall or fire grate made of crock or clay columns separating the fireplace and the firing chamber behind it. These crossdraught kilns require exit flues placed strategically in the kiln superstructure or at the rear base of the kiln. Chimneys are not necessary but do ensure optimal draught in the system.

Based on ground-plans and various other structural details, these basic types can be further broken down into subtypes. Two groups of vertical kilns, one with circular ground-plans, the other with rectangular ones, had their origins in the Roman period. The horizontal kilns followed two separate paths of development. One was that vertical kilns with raised kiln floors made of radially placed fire-bars gradually evolved into horizontal kilns with spoon-shaped firing floors. The other was a reduction in the internal construction of the kiln, which resulted in the development of horizontal single-chambered kilns or horizontal kilns with fire grates. These, in turn, were the basis for two further developments: oval stoneware kilns with under-built fireplaces in the Rhineland region and horizontal earthenware or stoneware kilns with elongated oval ground-plans, which were widely used in Lower Saxony, Saxony, Thuringia and Bavaria.

The most recent study on the topic (which, however, does not include the Anglo-American or Asian regions) was published in 2007 (Heege 2007; Heege 2013; Heege 2015). See Thuillier/Etienne Louis 2015 for the state of research in France. A comprehensive study of the central European porcelain kilns is still outstanding (Milly 1771; Hofmann 1921-1923; Weihs 1990, Weihs 1993; Krabath 2011; Matter 2012). For more information on the early 19th century state of technological development of industrial kilns in central Europe see Brongniart 1844.

Further references on pottery kilns

Töpferöfen – Fours de potiers – Pottery kilns – German

Fours de potiers – Töpferöfen – Pottery kilns – French

Pottery kilns – Fours de potiers – Töpferöfen – English

Pottenbakkersovens – Töpferöfen – Pottery kilns – Dutch

Töpferöfen – Pottery kilns – Fours de potiers: Glossary German – English – French

Pottery kilns in the 15th/16th centuries – German

Craftsmen’s Pottery Kilns in Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Switzerland – English

Pottery kilns in the Heimberg region and throughout Switzerland – German

Pottery kilns in Langenthal-German

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

German: Töperofen

French: Four, Four de potier

References:

Boschetti-Maradi 2006

Adriano Boschetti-Maradi, Gefässkeramik und Hafnerei in der Frühen Neuzeit im Kanton Bern (Schriften des Bernischen Historischen Museums 8), Bern 2006.

Brongniart 1844

Alexandre Brongniart, Traité des arts céramiques ou des poteries considérées dans leur histoire, leur pratique et leur théorie, Paris 1844.

Heege 2007

Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen-Pottery kilns-Fours de potiers. Die Erforschung frühmittelalterlicher bis neuzeitlicher Töpferöfen (6.-20. Jh.) in Belgien, den Niederlanden, Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (Basler Hefte zur Archäologie 4), Basel 2007.

Heege 2007

Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen-Pottery kilns-Fours de potiers. Die Erforschung frühmittelalterlicher bis neuzeitlicher Töpferöfen (6.-20. Jh.) in Belgien, den Niederlanden, Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz (Basler Hefte zur Archäologie 4), Basel 2007.

Heege 2009

Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen im 15./16. Jahrhundert. Innovation oder Stagnation?, in: Barbara Scholkmann/Sören Frommer/Christina Vossler u.a., Zwischen Tradition und Wandel. Archäologie des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts, Bd. 3 (Tübinger Forschungen zur historischen Archäologie), Büchenbach 2009, 181-190.

Heege 2010

Andreas Heege, Töpferöfen im Rheinland, in: Thomas Otten (Hrsg.), Fundgeschichten. Archäologie in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Köln 2010, 193-197.

Heege 2013

Andreas Heege, Craftmen’s Pottery Kilns in Belgium, The Netherlands, Germany, Austria and Switzerland, in: Natascha Mehler, Historical Archaeology in Central Europe (Society for Historical Archaeology, Special Publication Number 10), 2013, 279-294.

Heege 2015

Andreas Heege, Fours de potier du haut Moyen Âge en Allemagne, Suisse, Belgique, aux Pays-Bas et en Autriche, in: Freddy Thuillier/Etienne Louis, Tourner autour du pot … Les ateliers de potiers médiévaux du Ve au Xiie siècle dans l’espace européen (Publications du Centre de Recherches Archéologiques et Historiques Médievales, CRAHAM), Turnhout 2015, 583-593.

Hofmann 1921-1923

Friedrich H. Hofmann, Geschichte der Bayerischen Porzellan-Manufaktur Nymphenburg. Bd. I: Wirtschaftsgeschichte und Organisation. Bd. II: Werkbetrieb und Personal. Bd. III: Produktion und Verschleiß, Leipzig 1921-1923.

Krabath 2011

Stefan Krabath, Luxus in Scherben. Fürstenberger und Meissener Porzellan aus Grabungen, Dresden 2011.

Matter 2012

Annamaria Matter, Die archäologische Untersuchung in der ehemaligen Porzellanmanufaktur Kilchberg-Schooren. Keramikproduktion am linken Zürichseeufer 1763-1906 (Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 43), Zürich 2012.

Milly 1771

Nicolas Chrétien de Thy Comte de Milly, L’ art de la porcelaine (Nachdruck Slatkine Reprints Genève 1984) (Description des arts et des métiers), Paris 1771.

Thuillier/Etienne Louis 2015

Freddy Thuillier/Etienne Louis, Tourner autour du pot … Les ateliers de potiers médiévaux du Ve au Xiie siècle dans l’espace européen (Publications du Centre de Recherches Archéologiques et Historiques Médievales, CRAHAM), Turnhout 2015.

Weihs 1990

Michael Weihs, Ergebnisse der archäologischen Untersuchungen zwischen 1985 und 1989 auf dem Gelände der ehemaligen Porzellanmanufaktur Ludwigsburg, in: Wilhelm Siemen (Hrsg.), Die Ludwigsburger Porzellanmanufaktur einst und jetzt (Schriften und Kataloge des Museums der Deutschen Porzellanindustrie 23), Hohenberg 1990, 30-61.

Weihs 1993

Michael Weihs, Zum Abschluß der Grabungen in der Ludwigsburger Porzellanmanufaktur, in: Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 1992, 1993, 396-399.