Roland Blaettler, 2019

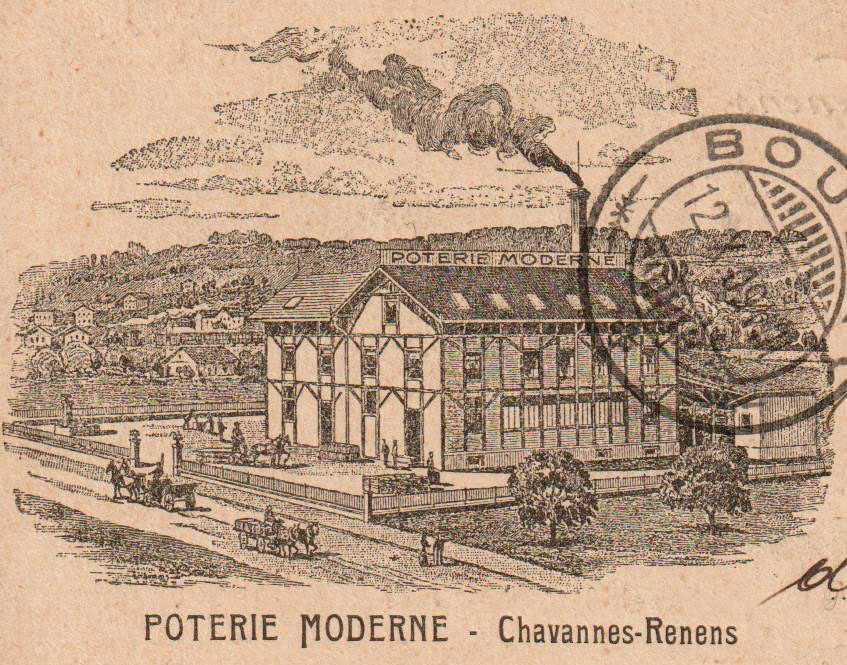

At the beginning of the 20th century, the status of Renens, a centre of pottery production, was considerably raised, first in 1902, when the “Poterie moderne” was founded in the small neighbouring community of Chavannes-près-Renens, and again in 1912, when the “Swiss School of Ceramics” opened its doors there (see the chapter Chavannes-près-Renens, Swiss School of Ceramics). Both institutions owed their existence to the personal initiative of Lucien Ménétrey (1853–1930), an “original and popular local personality, a man who undoubtedly played a prominent role in the region and contributed much to its development”, as was stated in his obituary (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 4th August 1930, p. 7 under “A. T.”). The same obituary provided the main points of information from which we have attempted to compile a biography for this important individual.

Lucien was the son of Jacques Louis Ménétrey (1820–1901), farmer, timber merchant and former mayor of Chavannes. After finishing school he moved to Uebendorf near Thun where he spent more than a year learning German. In 1879, the young man moved again, this time to Paris where he gave his debut as a “factor and so-called bank messenger” before visiting trading courses with the French Freemason’s lodge Grand Orient de France. There is no evidence to show if he had already joined the Freemasons at that stage, perhaps as a protégé of an elder “brother” (his father?). According to the obituary, Ménétrey appears to have lived in Paris for around fifteen years. It was not until 1894 that he returned to Chavannes, where he ran the village café for the following ten years. The same year he became a member of the municipal council for the Free Democratic Party. He would later describe himself as a “progressive liberal” (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 28th February 1901, 2).

In 1904, Ménétrey was elected mayor of Chavannes; he remained in office until 1913. At the elections in November 1913, Ménétrey’s party ticket was effectively defeated by the socialists together with a group of defecting liberals, and it was one of these defectors in fact who took over as mayor. An observer would note that “several names from Ménétrey’s ticket were listed among the winners” (La Revue dated 17th November 1913, 2; Nouvelliste vaudois of 6th December 1913, 3). It appears that not all party members stood behind the lively politician.

During his period in office, Lucien Ménétrey made a significant contribution to the modernisation of the community; the construction of the Bahnhofstrasse, the road linking the village with Renens train station, the electrification of street lighting and the construction of drinking water, gas and sewerage networks are all attributed to his efforts. When he took over the pottery company, he built fifteen workers’ houses for the employees.

As an active participant in the affairs of his region and canton, Ménétrey regularly voiced his opinions in the press, particularly in the Journal de Morges, using the pseudonyms “Pierre Dif”, “Pierre” or “Jean-Pierre”. In 1907 he was the only partner acting for the limited company that was publishing the Journal et Feuille d’avis de Renens founded in 1906 (SOGC, Vol. 26, 1908, 1361). Two years later he bought the newspaper (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 25th February 1909, 2).

Lucien Ménétrey was an active member of the chamber of commerce of the Canton of Vaud and held leading positions in the Freemasons’ lodges of Lausanne (Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz). The acknowledgment notices published by the family on the day after Ménétrey was buried (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 9th August 1930, 6), mention the “Le Progrès” Lodge, the “Souverain Chapitre L’Amitié” Chapter and the “Les Amis de la lumière” Areopagus, three Lausanne institutions which allowed members to attain as many as 30 (of 33) degrees in the Masonic hierarchy of the “Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite” (AASR). A second, shorter obituary published in the Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 5th August 1930 (p. 6), states that the deceased “attained the highest degree” in 1910.

The most lasting of Ménétrey’s legacies were undoubtedly two institutions related to the pottery industry, the first of which evolved into the most innovative pottery producer in the canton and the second of which for many years was the only technical pottery school worthy of the name in the French-speaking part of Switzerland.

Poterie moderne – Lucien Ménétrey, 1902-1905

Poterie moderne S. A. 1905-1972/73 (?)

Lucien Ménétrey registered his “Poterie moderne” in August 1902 (SOGC, Vol. 20, 1902, 1282). The company, which was housed in a brand-new building that is still standing today on the corner of Avenue de la Gare and Rue de la Blancherie, had probably been in operation for some time, as the first firing was carried out “around August 1902” (La Tribune de Lausanne dated 29th June 1905, 2–3). The same article states that following “some unavoidable changes, the factory started to produce wares at the site which immediately began to attract attention and were highly regarded”. The article also makes it clear that the raw materials could be found on site which was ideal for the company.

Starting in September, Ménétrey published advertisements to promote his “studio ceramics and utilitarian wares” as well as his architectural and stove ceramics. The advertisements also announced that his “series of studio ceramics” would be exhibited in the shop windows of the Martinioni department store on Rue Centrale in Lausanne (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 12th September 1902, 4). Three days later the same newspaper hailed the establishment of the new firm: “There are not many workshops in Switzerland that produce studio ceramics. The best-known of these is in Thun. Ferney-Voltaire in the Pays de Gex region also has a reputation that goes way back, and lovers of pretty knick-knacks are sure to buy them there. A third factory has been opened outside the gates of the capital city near the train station in Renens […]” (issue dated 15th September 1902, 2).

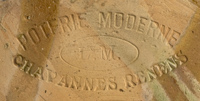

Vessels for everyday use and cookware were undoubtedly the main products made by the Poterie moderne and the style was similar to that of other pottery producers in the Lake Geneva region. This included a large green-glazed slipped earthenware bowl with a pouring lip bearing the first impressed mark of the company with the initials of its owner – “L. M.” in an oval frame (MHL AA.46.D.22). This mark was officially registered on 17th September 1902 (SOGC, Volume 20, 1902, 1362).

It is the only marked example to have survived from what must surely have been quite a substantial production of undecorated utilitarian wares.

Thanks to another marked piece now in the Val-de-Travers Regional Museum in Môtiers, Canton of Neuchâtel, we know that the Poterie moderne also produced decorated cylindrical milk jugs with thickened rims, another vessel shape that was characteristic of the slipped earthenware in the region of Lake Geneva (MRVT Nr. 26).

Ambitious “artistic” objects associated with the early phase of the company’s production can be found among the works commissioned by various municipalities in 1903 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Canton of Vaud (MHV 5245; MVVE 5180; MVM M 909; MCAHL HIS 11-19; MCAHL HIS 11-16; MCAHL HIS 11-10; MCAHL HIS 11-15; MCAHL HIS 11-12; MCAHL HIS 11-11; MHPN MH-1998-95). Most bear the impressed mark mentioned above, sometimes framed by the words “POTERIE MODERNE CHAVANNES RENENS” (MCAHL HIS 11-14).

Like some of his colleagues, Ménétrey too capitalised on the wave of euphoria felt by the public about the centenary. As far as we know, he was asked to produce commemorative wares for at least seven municipalities: Pully, Cully, Grandson, Vevey, Moudon, Riex and Vuarrens. Like the vessels produced by Samuel Jaccard in Renens, most of Ménétrey’s patterns consisted of heraldic motifs and the entire special series was made in the traditional technique of adding sprigs to slipped earthenware vessels and then coating them in a lead-based glaze. However, Ménétrey’s wares were more refined in their details than Jaccard’s. Some of the more exquisite sprigs were made from white clay reminiscent of refined white earthenware and the imprinted inscriptions – the names of municipalities or the heraldic motto of the Canton of Vaud – were stamped in block letters.

The only soup bowl known to have survived from the commemorative series for the town of Moudon (MVM M 909) allows us to trace a range of special techniques developed by Ménétrey’s potters, including a way of creating a “naturalistic” design for twig-shaped handles.

In the Conteur vaudois journal dated 18th June 1904, a Mr J. M. gives an account of a visit to the potter’s workshop accompanied by Ménétrey. In his article, this individual describes the skilfully crafted pottery “with its interesting shapes and bright colours” and colourful poured glaze decorations on the one hand, and the “large amounts of everyday wares made from red or yellow clay and decorated with bizarre, multicoloured patterns that our farmers remain so fond of” on the other. The only motif that is known to date that could possibly exhibit such “bizarre, multicoloured patterns” is precisely the marbled decoration on the milk jug in the museum at Môtiers (MRVT Nr. 26).

In the spring of 1905, Lucien Ménétrey, having “realised that this industry does indeed pay decent dividends”, decided to turn his firm into a public limited company “to attract the attention of those who are directly linked to it, be it as producers or as traders” (Tribune de Lausanne dated 29th June 1905, 2-3). Some forty subscribers thus gathered on 20th March that year to set up the new enterprise. The journalist from the Tribune also stated that, taking encouragement from French enterprises such as “Le Louvre”, “Le Bon Marché” or “Familistère de Guise”, Ménétrey had decided to allow the workers of the new company to participate in its success by giving them an option to buy stocks at a special rate, to set up accident insurance paid for by the company and to divide ten percent of its profits among the director and the employees.

On 1st April 1905 the old company name was deleted and the “Poterie moderne de Chavannes-Renens S. A.” was newly registered and published in the Schweizerisches Handelsamtsblatt [Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, SOGC] (Vol. 23, 1905, 579). The new company’s purpose was to take over the assets of the preceding enterprise, including its buildings, materials and client base. The capital funds of 100 000 Swiss francs were divided into 400 bearer shares. Ménétrey was the chairman of the board of directors, while Henri Magnin a native of Collex-Bossy in the Canton of Geneva but resident in Chavannes became the managing director. A few years before that, Magnin had chaired the Chambre syndicale des ouvriers tourneurs en poterie du canton de Genève [Association of potters in the Canton of Geneva] (see the chapter Slipped earthenware from the Lake Geneva region).

Two years later Magnin vacated the position of managing director and was replaced by his son-in-law Henri Dusserre (1882–1950; Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 18th October 1907, 4). Following in Ménétrey’s footsteps, Dusserre, also a member of the Free Democratic Party, was elected to the municipal council of Chavannes in 1921 and became mayor in 1925. He held the office until September 1945.

Shortly after Dusserre had become managing director of the company and in view of the confusion that had been caused by an alleged merger between the Jaccard and Pasquier-Castella potteries, he was forced to make the following public announcement:

“The management of the Poterie moderne would like its esteemed customers to know that it has not merged with the other works in Renens. The delay in many of the deliveries is purely because of the large number of orders we have received.” (La Revue dated 24th December 1907, 4).

From 1908, various notices published in the Indicateur vaudois journal advertised a new series of products: heat-resistant cookware. We have not been able to find any examples of cookware, or of any other type of pottery, that could be identified as having been produced by the Poterie moderne over the following twenty years. What we do know, however, is that the company won first prize at the 1912 Montreux Gardening Exhibition (Le Grutli, 18th October 1912, 3). In 1913, the Lausanne Artistique newspaper ran a readers’ competition with several prizes. First prize was a pair of large majolica vases from the Poterie moderne worth 25 Swiss francs (issue dated 15th November 1913, 3).

On 23rd May 1925 the company registered a new mark, this time in the shape of a rectangle with the initials “PM” (SOGC, Vol. 43, 1925, 1049). So far, we have not been able to find any object that bears this new factory mark.

In a report on the Comptoir de Lausanne economic fair, the L’Artistique newspaper dated 24th September 1927 described the Poterie moderne’s exhibition space. The journalist was particularly taken with an “unusual breakfast place setting for two in various colours”, “pots and bowls with the official motifs of the Fête des vignerons (winegrowing festival) as well as charming little amphoras that are proving very popular and are selling like hotcakes”. The Poterie moderne had indeed been chosen by the festival committee to be the official supplier of a series of decorative crockery with underglaze painted decoration (advertisement in the Revue dated 30th and 31st July 1927, p. 4). Another advert placed by the company Pamblanc Frères, the only authorised retailer for the city of Lausanne, shows three pieces from this commemorative series, a shallow dish with a drummer wearing historical costume, one with a female grape picker and another with a male grape picker both wearing traditional costume (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 28th July, p. 7).

The website notrehistoire.ch shows a photograph of the shallow dish with the female grape picker and another shallow dish with a miller (?) holding a glass of wine in his hand. According to a comment on the two photographs by Christian Gerber, the prototypes for the shallow dishes had been made at the Swiss School of Ceramics by his father Paul Gerber (1900–1977) who taught at the school for a couple of years (see the chapter Eysins, Paul Gerber). The Swiss National Museum houses a bonbonniere made by the Poterie moderne for the 1927 festival (SNM LM-167681). Its basic colour is a speckled blue and its lid bears an image of an Alpine herdsman smoking a pipe. This object has also been attributed to Paul Gerber.

Thanks to the broad appeal of the Fête des vignerons and the inspiring collaboration with the nearby school of ceramics, the 1927 commission became highly profitable for the Poterie moderne, as it had now made a name for itself as the most prolific institution in the canton in the field of studio ceramics production – a reputation it would retain for some time to come. It also meant that it was chosen to be the official supplier to the 24th Eidgenössisches Sängerfest (Federal Singing Festival) held in Lausanne from 6th to 17th July 1928 (Tribune de Lausanne dated 6th July 1928, 1–2).

On this occasion the Poterie moderne produced a range of plates showing some of the costumes that had been designed by the Vaud painter Ernest Biéler (1863–1948) for a grand spectacle created by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze that was entitled “Notre Pays” (Our Nation) and was set to be one of the highlights of the festival (MHL AA.46.B.58A; MHL AA.46.B.58B; MHL AA.VL 89 Di 534.64). The same motifs were printed on postcards (Tribune de Lausanne dated 6th July 1928, Fig. p. 1). The plates from 1928 bore a new stamped mark in the shape of an escutcheon applied under the glaze. It showed a bridge arch and three cherries, the two main symbols of the coat of arms of Chavannes-près-Renens. Above and below these symbols are the inscriptions “POMONE” (probably a contraction of “POterie MOderNE”) and “CHAVANNES” (see MHL AA.46.B.58B). It is worth noting that the coat of arms, which was adopted in 1905, was personally designed by Mayor Lucien Ménétrey (Revue historique vaudoise, 28, 1920, 62)!

While the number of examples that have so far been identified remains surprisingly low, we can still assume that commissions for commemorative objects remained a regular source of income for the Poterie moderne for many decades, as was the case for Marcel Noverraz in Carouge. They were all made from earthenware with painted or stencilled decorations on a very smooth coat of slip (probably applied by air-brush) and were often produced with careful attention to detail (see e.g. MHL AA.46.B.56; MHL AA.VL 89 Di 534.66).

In a brief history of the pottery industry in Renens and Chavannes (see Renens VD, Les poteries) published in 1929, it’s author, school inspector Grivat, stated that the Poterie moderne, besides utilitarian/everyday wares also “[…] produced studio ceramics, the more interesting examples of which can also be purchased in Lausanne, Montreux and Zermatt. Some have even been shipped to France and England” (Feuille d’avis du District de la Vallée dated 21st November 1929, 7). This important production segment seems to have been aimed at tourists from abroad.

In the spring of 1932, the Poterie moderne was faced with strike action by all eight of its potters, which lasted from 12th April until the middle of August. Claiming that production costs no longer allowed him to keep pace with his rivals and that the company was suffering from chronic financial shortfalls, Dusserre had proposed a ten percent cut to workers’ wages. The potters were radically opposed to this and pointed to the fact that – by their own reckoning – their wages were already lower than those paid by other potteries in the region, including Renens, Colovrex and Carouge. The cantonal board of arbitration tried to reach a compromise by proposing a five percent cut instead. Management was in favour, but the strikers, with support from the union cartel of Vaud, refused to yield and voted to continue the fight (Le Droit du Peuple dated 19th April 1932, 4). On 1st June the Feuille d’avis de Lausanne newspaper (p. 6) published a piece outlining Dusserre’s position. He stated that the average potter’s salary had been raised from 280 to 370 Swiss francs in 1931 and that a five-percent cut could easily be offset by the fact that the workers were being paid piece rate. The director again bemoaned the loss of revenue and the associated price collapse. He also complained about the aggressive behaviour of the Federation of Timber and Construction Workers, who had not hesitated, he claimed, to intimidate workers who had decided not to participate in the strike. They had also put pressure on the traders who were continuing to do business with the Poterie moderne by threatening to boycott them. The reply from the “Association of Renens Potters” published in part in the Feuille d’avis de Lausanne and then in detail in Le Droit du Peuple dated 16th June (p. 5), stated that Dusserre had replaced at least some of the strikers with two young potters who had just graduated from the Swiss School of Ceramics and a “kroumir” (a despicable strikebreaker). A few days later, Dusserre did, in fact, publish a notice declaring that “despite the strike, some potters continue to work at the Poterie moderne in Chavannes” (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 25th June 1932, 8). The dispute was finally settled in August, though we have not been able to find even the slightest hint of what was agreed. Le Droit du Peuple dated 29th August 1932 (p. 5) did, however, proclaim: “the strike has ended”.

Returning to the production of the Poterie moderne, which we know was never completely halted by the turn of events, we can say that a new stamped mark in the shape of an inverted triangle was probably introduced in the early 1930s. The triangle contained the same heraldic motifs as before but now had the circumscription “CHAVANNES POTERIE MODERNE”, in many cases accompanied by the words “hand-painted” (see MHL AA.46.B.56).

A third stamped mark was used in the late 1930s. In this case, the inscriptions “POTERIE MODERNE CHAVANNES” and “hand-painted” were encased in a circle, which also contained three cherries; the bridge arch had been dropped. The only example that we have actually been able to find is on the back of a commemorative plate from 1939 which is housed in the Museum of Lake Geneva in Nyon (ML 2012-17-3).

To supplement the commemorative shallow dishes, the company attempted to develop a new niche product: objects with family coats of arms. An advertisement for “armorial plates” run by the Poterie moderne tells us that the company even offered “research free of charge”, probably in consultation with experienced heraldists (e.g. in Le Grutli dated 9th March 1934, 3).

Only two relatively late specimens from the Poterie moderne’s actual line of “studio ceramics” have survived. The objects donated to the Musée des arts décoratifs de Lausanne [Museum of Decorative Arts] in 1949, while a nod to the spirit of the modern age, were still made from slipped earthenware, some with coloured glazes (MHL AA.MI.1893; MHL AA.MI.1892). Both objects are stamped with a mark consisting of the words “DE CHAVANNES SUISSE” arranged in a circle around three cherries (see MHL AA.MI.1892). This particular mark was probably introduced in the second half of the 1940s.

The same mark can be seen on the back of a commemorative plate dated 1953 (MHL AA.VL 92 C 2282). Surprisingly for a company that remained in operation until the early 1970s, this plate is the most recent example in the public collections of the Canton of Vaud. Another aspect that makes this plate unusual is its production technique; it was made of faience, a type of pottery that is characterised by its lead-tin glaze. Whilst the technique itself was thousands of years old, it was completely new to the range of products created by the Poterie moderne. Although the 1953 plate is the only piece of faience associated with the Poterie moderne, we believe that the company began to use the technique around that time – the beginning of the 1950s – but did not abandon production of its traditional slipped earthenware.

From 20th February to 30th March 1956, the “Innovation” department store in Lausanne staged an “Exhibition of Vaud’s Industry”. The Poterie moderne was one of 21 companies that were invited to exhibit their wares. On 20th February, Innovation took out a four-page advertisement in the Feuille d’avis de Lausanne with brief descriptions of the companies involved. The Poterie moderne is described thus: “[…] the company was commissioned to create commemorative plates and elaborately decorated vases for the large Wine Festival of 1927, which were considered some of the highest-quality studio ceramics. […] Noteworthy among the most beautiful objects of that style, the attractive faience pieces are adorned with a lead-tin glaze in magnificent pastel shades.” (p. 7).

There is no evidence of the evolution of the company in the 1940s, neither with regard to its ceramic objects nor in terms of media coverage. The most important information available to us today comes from the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce and mainly concerns the changes that took place at management level. In 1944, for instance, the company changed its statutes. Besides the industrial manufacture of pottery, the company would now reserve the right to “extend [its activities] to all areas of business related to this line of work”; it would “also be permitted to take part, directly or indirectly, in all industries or enterprises that are in any way related to its own line of business, acquire shares, run financial operations in commerce and industry as well as in trade and real estate that are associated with the purpose of the company” (SOGC, Vol. 63, 1945, 371–372).

This significant and ambitious change to the statutes was clearly linked to Roger Corthésy and even more so to Antoine Pfister, two figures that had been newly appointed to the company’s board of directors. Both were made executive directors alongside Henri Dusserre, the company director and president of the board. At the same time his position as president was scaled back in that his “sole signature right as director” was revoked and at least two of the three executive directors, Dusserre, Pfister and Corthésy, were now required to make decisions on behalf of the company (SOGC, Vol. 63, 1945, 372).

At the general meeting of shareholders in June 1945, Dusserre announced his resignation as member and president of the company board and Pfister took over his duties (SOGC Vol. 63, 1945, 1923). From as early as 1946, Antoine Pfister’s private residence in Renens was listed as that of the “Director of the Poterie moderne”, while Dusserre was still using the same title but only at the company’s address. Was Pfister perhaps brought in to relieve Dusserre whose health was beginning to fail, or did the sharing of responsibility between two executive directors simply mirror the new power structure within the company? When Dusserre died in 1950 (La Nouvelle Revue de Lausanne, 21st December, p. 8) Pfister took over management of the company and appears to have retained the position until his own death in 1982.

Originally from Tuggen in the Canton of Schwyz, Antoine Pfister had already been working in the wholesale pottery trade for several years before he joined the Poterie moderne. In 1940 he founded the company “A. Pfister Keramik” [A. Pfister Pottery] in Zurich (SOGC, Vol. 58, 1940, 619). In 1945 he moved the company seat to his private address in Renens (SOGC, Vol. 63, 1945, 1939). In July of the following year a new limited company was listed at 6 Avenue Fraisse in Lausanne under the name of “A. Pfister S.A.” to trade wholesale in ceramic, glass and goldsmithing products. The declared purpose of the company was “to import, export and factor these products and to run storehouses for other companies from abroad”. The executive directors of the company were Antoine Pfister and Alfred Froidevaux, who was probably Pfister’s brother-in-law (SOGC Vol. 64, 1946, 2094). Five years later, the seat of this commercial enterprise was moved to 33 Avenue de la Gare in Chavannes-près-Renens, which was the address of the Poterie moderne (SOGC, Vol. 69, 1951, 1794). In 1981, Pfister and Froidevaux resigned from the company board (SOGC Vol. 100, 1982, 98). The company continued to trade under the same name, though its seat was moved to Stäfa in the Canton of Zurich in 1985.

Roger Corthésy (who died in 1990 at the age of 77) is a little harder to trace. We have tried to reconstruct his career in as much detail as possible, but we have had to rely almost exclusively on information from various directories for the Canton of Vaud. Corthésy graduated as a potter from the Swiss School of Ceramics in 1932 (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 30th March 1932, p. 2). He is listed as a ceramicist in the Indicateur pratique du Canton de Vaud (trade directory) for the years 1933 and 1934. At that time he lived in the Bellevaux district of Lausanne. The Annuaire et indicateur vaudois réunis (telephone book) mentions a policeman named Roger Corthésy from 1938/39 to 1946 as residing in Lausanne at Chemin de la Motte until 1942 and then at 20 Avenue Riant-Mont. From 1947 to 1960, a Roger Corthésy is listed at the same address as “Director of the School of Ceramics in Chavannes” and from 1961 to 1982 as “Executive Director of the Poterie moderne”. Neither the address nor the telephone number have changed, so it seems that we are dealing with the same person all the time.

We believe that Roger Corthésy was not able to find employment in his original profession, which prompted him to seek a more stable career as a policeman. His original training would obviously explain how he was involved in the running of the school of ceramics from as early as 1947. What is odd is that all directories list him as a “director” only at his home address and never in any of the entries concerning the school. Nor is his name ever mentioned by the media in relation to the school in Chavannes.

With regard to his association with the Poterie moderne we know that he became executive director in 1944. It is quite likely that, as time went on – and perhaps after Dusserre’s death – Corthésy took on more responsibility, particularly with regard to administrative duties. He nevertheless takes on the title “Administrative Director of the Poterie moderne” in the directories from 1961 to 1982, but again this title only appears in relation to his home address, while he is not listed in any of the company entries. The information gleaned from these directories is probably not completely reliable, particularly when it comes to individual entries. The media, for example, were identifying Corthésy as “Director of the Poterie moderne” from as early as 1954 (Feuille d’avis de Vevey dated 4th October 1954, p. 6). And better still: two objects donated by the company to the Musée d’art industriel et d’art décoratif de Lausanne in 1949 are clearly recorded in the old museum inventories as “a donation from M. Corthésy, Director of the Poterie moderne”, at a time when he was also being identified as “Director of the School of Ceramics”!

It is obvious that these ambiguities can only be resolved by carrying out further research, particularly in the records of the cantonal archive. As it stands, we know that Corthésy resigned from the company board in 1972, at which stage production appears to have ceased (SOGC, Vol. 90, 1972, 383).

The company name “Poterie moderne” was retained until 1997, at which stage it was changed to “S I. Gare 33” and the purpose of the company was recorded as “real estate business” (SOGC, Vol. 115, 1997, 6492). The fact that the original company name was retained for so long is rather confusing, since the production of pottery ceased long before 1997. The changes to the statutes made in 1944 meant that Pfister reserved the right, from the very beginning of his involvement, to diversify the company activities. Did this actually happen, and if so, when did it occur and what were these new activities? How were the pottery factory and Pfister’s second company, “A. Pfister S. A.”, connected? These questions cannot be answered for the time being.

We know from advertisements in the print media that the pottery factory was still seeking to employ glazers in 1961 and potters in 1962. Up to 1973, the directories list the Poterie moderne under “pottery factories”; from 1974 to 1980 it only appears in the alphabetical list of inhabitants and after 1981 it is no longer mentioned in any of the directories. We can therefore assume that the company closed down in 1971/72 without any specific reports in the press.

Despite the fact that its original operation had ceased, the Poterie moderne S. A. continued to exist as a limited company. As we can glean from the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, the shareholders continued to be invited to attend annual general meetings until 1992. In 1977, the share capital was reduced by cancelling the old shares which had a nominal value of 5 Swiss francs. In the following year, 400 participation certificates were annulled. In 1978, the statutes were changed at an extraordinary general meeting though the precise nature of the changes was not recorded. The shareholders were actually paid dividends for the years 1978 to 1989.

Antoine Pfister died in November 1982 (24 Heures dated 10th November 1982); Alfred Froidevaux succeeded him as president of the board of directors and Katrin Pfister, the deceased’s daughter, was appointed managing director with sole power of representation (SOGC, Vol. 101, 1983, 3790). Having been absent from the directories since 1981, the company name “Poterie moderne de Chavannes-près-Renens S. A.” appears one last time in 1996/97 at the private residence of Katrin Pfister in Corcelles-le-Jorat, where she is named as the “sole managing director”.

A special case: studio ceramics by Jules Merminod, 1907-1912

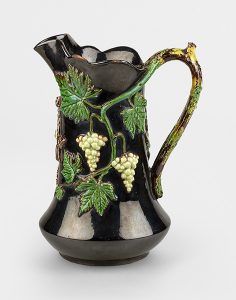

At the Musée de la vigne, du vin et de l’étiquette [Vineyard Museum] at Château d’Aigle, we came across a slipped earthenware jug with moulded, shaped and applied relief decoration in the form of vine tendrils and a masonic motif (MVVE 5095). The design was obviously inspired by the well-known patriotic jugs from the Knecht potteries (see, e.g., MVVE 2411 and MVVE 2355). The shape of this jug is an independent creation, and its quality is as good as that of the Knecht jugs.

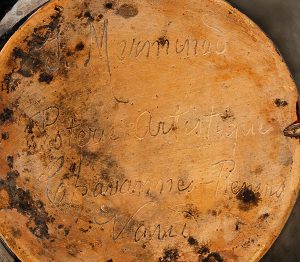

What is unusual for a product of this type, however, is the incised signature on the base of the object, which reads: “J. Merminod – studio ceramics – Chavannes-Renens – Vaud”. Presuming that there had to have been a hitherto unknown pottery workshop in Chavannes, we referred back to the directories and found that the Indicateur vaudois from the period between 1907 and 1912 did, indeed, list a Jules Merminod (his first name occasionally being abbreviated to J.-L.) under the heading “studio ceramics” in Chavannes, listed directly below the Poterie moderne S. A., which itself is preceded by the designation “pottery factory”. An important detail here is that “Poterie moderne” is added alongside Merminod’s name.

We can therefore conclude that Merminod did not run an independent workshop but had some sort of special arrangement with the Poterie moderne that allowed him, for example, to sign his own products. It is possible that he was expected to make his specialist skills available to the company in return. It is also worth noting that Merminod is not listed as a business owner in the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce. After 1912 there are no listings for a potter named Merminod in any of the directories.

The jug from Château d’Aigle remains an isolated case. This could be taken to mean that Merminod’s personal output was not widely known and that he probably also worked for the Poterie moderne. Despite this he maintained the status of studio potter for at least five or six years. It is, of course, also possible, or even quite likely, that he did not sign all of his works.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

Sources:

The press in the Cantons of Vaud and Geneva and the directories of the Canton of Vaud (accessed via the Scriptorium website of the Cantonal and University Library in Lausanne and on letempsarchives.ch)

The Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce, from 1883 (available on e-periodica.ch)

References:

Ferney-Voltaire 1984

Ferney-Voltaire. Pages d’histoire. Ferney-Voltaire/Annecy 1984.

Huguenin 2010

Claire Huguenin (éd.), Patrimoines en stock. Les collections de Chillon. Une exposition du Musée cantonal d’archéologie et d’histoire de Lausanne en collaboration avec la Fondation du château de Chillon, Espace Arlaud, Lausanne et Château de Chillon. Lausanne 2010.