The School of Ceramics collection in CERAMICA CH

Roland Blaettler, 2019

The advances made in the industrial development of Switzerland in the second half of the 19th century led to an ever-growing demand for a broader system of training for young workers, at a time when the Federal Government was very limited in its powers over Swiss educational policies. The first vocational schools were often established by companies, groups of companies or municipalities, usually with a lot of support from local public coffers. The involvement of the Federal Government only became more relevant in 1884 when a Federal Decree introduced state subsidies for vocational courses for male trainees (Lüthi 2017, 120–121).

This was the context within which the Swiss School of Ceramics was established in Chavannes-près-Renens in 1911 on the initiative of its mayor Lucien Ménétrey (1853-1930). Ménétrey was an outstanding personality, freemason, member of the Free Democratic Party (he saw himself as a “progressive liberal”) and entrepreneur who was actively involved in various areas and in 1902 had set up a pottery making factory in Chavannes under the name “Poterie moderne S. A.” (see the chapter “havannes-près-Renens VD, Poterie moderne (S.A.), 1902-1972/73»).

The idea for the lively businessman’s new project came from what he had experienced as an entrepreneur and the constant struggle to find qualified workers from Switzerland. Like his colleagues in the region, he was very often forced to recruit potters from France, particularly from the region of Ferney-Voltaire or Savoy, or even from Germany or Italy. “Unfortunately, we have been shown to be too dependent on our neighbouring countries”, he would later say (La Revue dated 13th April 1908, 2). Ménétrey appears to have nurtured the idea of opening a school of ceramics from as early as 1903, at which time he began to work on putting it into practice by visiting several similar institutions throughout Europe (Gazette de Lausanne dated 3rd September 1912, 3).

In 1908 the project began to materialise and Ménétrey put in place a strategy which aimed to secure financial support from the authorities, particularly when a request was made at the annual shareholders’ meeting of his pottery making company that “the initiators behind the project of setting up a school of ceramics should receive support from the cantonal and federal administrative bodies”. In a report on the meeting the La Tribune de Lausanne also made reference to the programme that Ménétrey had developed for the project: “A teaching programme has been worked out, a site for the school has been selected, the plans already exist, and a construction and operating budget has been diligently drawn up”. The municipality would own the building and would stand surety for it. “The consortium would initially provide funding of 20,000 francs towards construction of the school. A mortgage loan of 30,000 francs would be raised and the interest guaranteed by a state subsidy which the enterprise hopes to receive from the Federal Government. The remaining amount (20,000 francs) would be applied for in the form of state subsidies.” The school would be managed by a board of three delegates, one from the Department of Public Education, one from the municipal office of Chavannes and one from the schools inspectorate of the municipal office. The principal and instructors would be appointed by the Council of State for the Canton of Vaud upon recommendation by the board. All apprentices or students would have to be Swiss citizens”. The annual operating budget would be an estimated 6,000 francs (issue dated 31st May 1908, 2).

The Gazette de Lausanne dated 4th August 1908 (p. 3) announced further information about the financial arrangements Ménétrey had put in place. They included the construction of the building on land owned by the municipality of Chavannes, which would provide the site, the clay needed for the running of the school as well as a “small subsidy” for free. The state would contribute approximately one third of the construction costs. It was reported that the Department of Public Education had signalled a willingness to subsidise the administration of the school. The Federal Government on the other hand had also agreed to make a contribution. School fees and the proceeds from the sale of some of the works produced would furthermore help to balance “the schools’ modest budget”. The curriculum, at that stage at least, consisted of the potters’ basic training as well as some advanced artistic training, for instance courses in decorative drawing. There were even plans to provide free courses in painting on porcelain, earthenware or faience. “Because Renens is located on the outskirts of Lausanne, the courses will surely be attended by a large number of students.” The founder’s expectations would be revealed to be far too optimistic … particularly as the municipality of Chavannes did not purchase the building until 1970, at which point the school had long since been moved to another site.

In terms of the curriculum, Ménétrey’s vision was rather ambitious. He wanted his potters to be as well-trained and independent as possible: “A good worker has to be able to throw, trim and even fire, know a little bit about moulding, and even if he is lacking in taste, he must know how to decorate his products […]. All the advances in the industry mean that it is almost impossible for an apprentice to be adept in every area of his craft. Usually, a young trainee will remain under the guidance of a worker, will become specialised and be more or less capable of carrying out only one particular part of the craft. This is the situation the school must try to remedy” (La Revue dated 20th July 1908, 1).

The new institution was a public limited company and its inaugural meeting took place on 10th July 1911 (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 30th June 1911, 4). On 9th August 1911, the company was registered in the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce (SOGC). The entry reads: “A public limited company has been registered under the name Société de l’École suisse de céramique de Chavannes-Renens. The company aims to set up a Swiss school of ceramics, construct a school building to state-approved designs, take ownership of the property which will be provided free of charge, and receive both extraordinary and annual cantonal and federal subsidies, organise the school, and manage and run it. […] The statutes are dated 10th July 1911. […] the members of the board of administration are: Lucien Ménétrey, Louis Laffely and Louis Michaud” (SOGC Vol. 29, 1911, 1370). Laffely (1855–1925) was an entrepreneur, mayor of Morges and member of the cantonal parliament; Louis Michaud (1874–1954) was the son of the director of the Manufacture de poteries fines de Nyon. He succeeded his father in 1917 and ran the company until 1936.

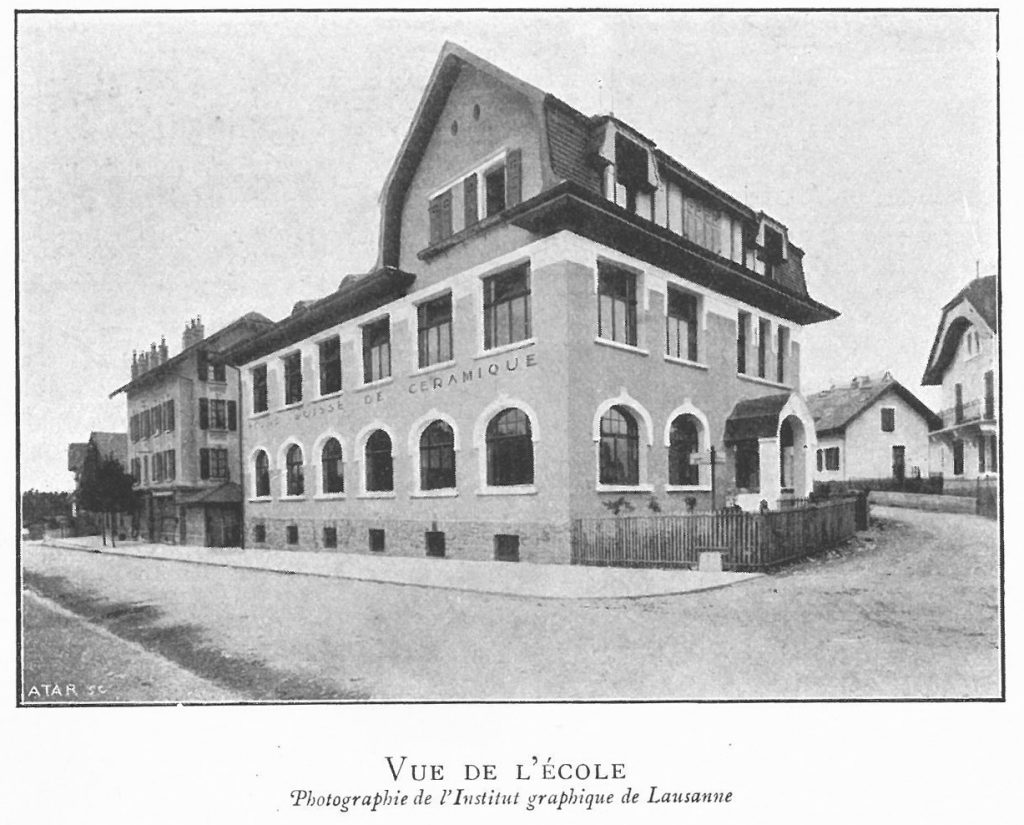

In September 1911 the board of administration awarded the contract to begin the construction work. “By Christmas the building should have a roof. The interior work and the fixtures and fittings will be completed over the winter months. Construction will be completed by the end of March 1912 at the latest […] and the Swiss School of Ceramics will open its doors in early April” (Avis de Lausanne dated 7th September 1911, 16).

The grand opening, however, did not take place until 1st September 1912. To mark the occasion, the La Revue newspaper dated 2nd September (p. 2) recalled the timeline of the “adventure” once again: the designs submitted by the Lausanne architect Eugène d’Okolski are approved on 3rd March 1909, “selflessly supported by Mr Ménétrey, mayor of Chavannes”; on 20th May 1911 the Council of State orders a subsidy of 20,000 Swiss francs for the construction of the school; the statutes of the Société de l’École suisse de céramique are passed by the Council of State on 30th January 1912 and finally, Maurice Savreux “a former professor at the School of Ceramics in Vierzon” is appointed director of the institution in May 1912.

In his speech at the opening ceremony, Louis Gauthier, head of the Department for Vocational Education, stressed that “the support received from the directors of the Manufacture nationale de Sèvres was particularly helpful in choosing a director [for the school]” (Gazette de Lausanne dated 3rd September 1912, 3). Apparently Ménétrey had sought advice from the management of the prestigious manufactory, who had probably recommended Maurice Savreux. Initial approaches appear to have been made as early as 1911 (see below). Savreux had a solid background in both technique and artistry, and his influence on the course curriculum – as published in detail in 1914 – was evident.

Having been introduced to the art of painting at the school of arts in Lille from 1899 to 1901, Maurice Savreux (1884–1971) attended the Sèvres School of Ceramics (l’École de céramique de Sèvres) between 1901 and 1905, graduating with a diploma in ceramic engineering. He then returned to painting and between 1907 and 1910 attended various courses at the École nationale des beaux-arts de Paris (School of Fine Arts in Paris), after which he took up teaching posts at the École nationale professionnelle de Vierzon (Vocational College at Vierzon) and the École des beaux-arts de Bourges (School of Fine Arts in Bourges). According to Émile Langlade, “Maurice Savreux was still teaching in Vierzon in 1911, when he received the invitation from Switzerland. As Switzerland was eager to open a national school of ceramics at the time, he, as a former student at our school in Sèvres, was considered a potential candidate” (Langlade 1938, 148). Mobilised as a non-commissioned infantry officer during the First World War, he was wounded in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. Having spent a year recuperating in hospital, he was demobilised and awarded three distinctions as well as the National Order of the Legion of Honour. Between 1917 and 1926, Savreux was chief curator of the Musée de Sèvres (French National Ceramics Museum) and also spent much of his time painting. Having taken part in the “Phoney War” during the Second World War, he was tasked with managing the Manufacture de Sèvres for a short while in 1946/47, and between 1907 and 1947, he also provided the manufactory with several paintings. Most of his paintings were landscapes and still-lifes (Langlade 1938, 143-164; Le Delarge, Dictionnaire des arts plastiques modernes et contemporains, www.ledelarge.fr; Sèvres Workmen’s List http://www.thefrenchporcelainsociety.com).

In his own inaugural address Ménétrey did not fail to mention his “regret that the state and the Federal Government did not reveal themselves to be more open in terms of vocational education matters”. He reminded his audience that “this school aims to teach our youth how to work” and expressed his hope that “a new Swiss style of ceramics will emerge” (La Revue dated 2nd September, 2). A report on the event in the Gazette de Lausanne dated 3rd September (p. 3) returns to Ménétrey’s ambitious vision: “We aim to combine theory and practice. Our school will be the mother house for both employers and employees alike to come and learn about new processes and the latest inventions, where everyone will meet everyone else, while now it still seems that everyone is jealously guarding their own production techniques, though most are in fact open secrets […]. We will endeavour to create our own Swiss style, which will not be inspired by Hodler or the designs the national bank puts on our banknotes, and this will not be difficult … Our school will have places for ten students per year, or forty over the four-year course.”

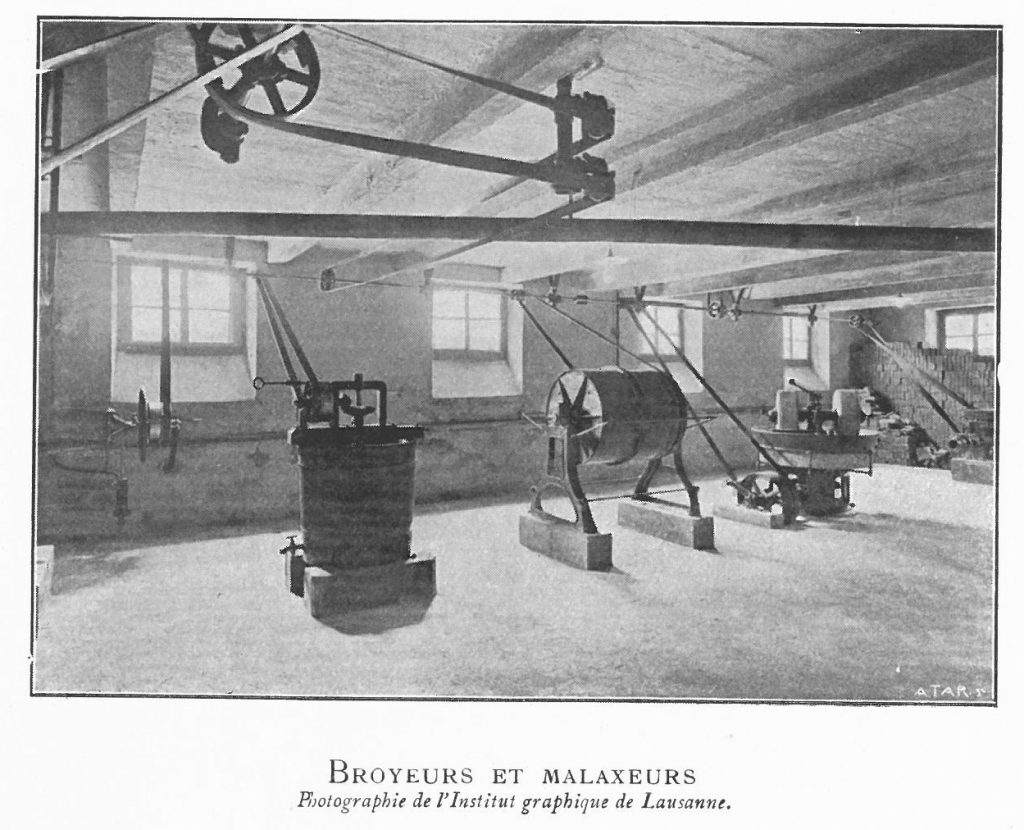

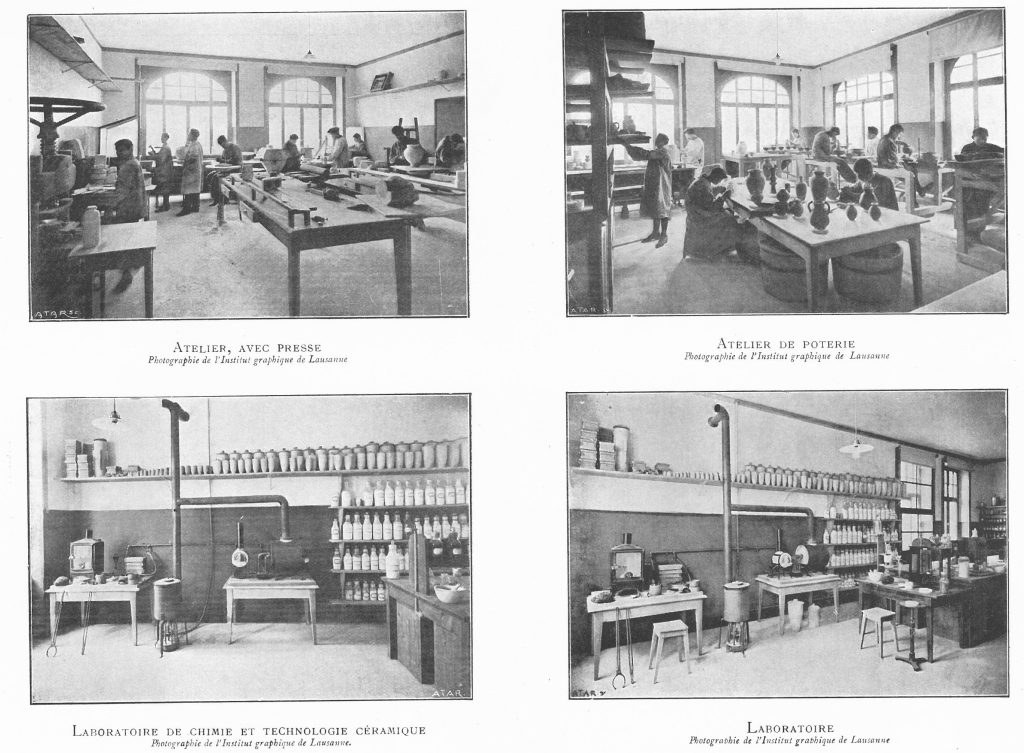

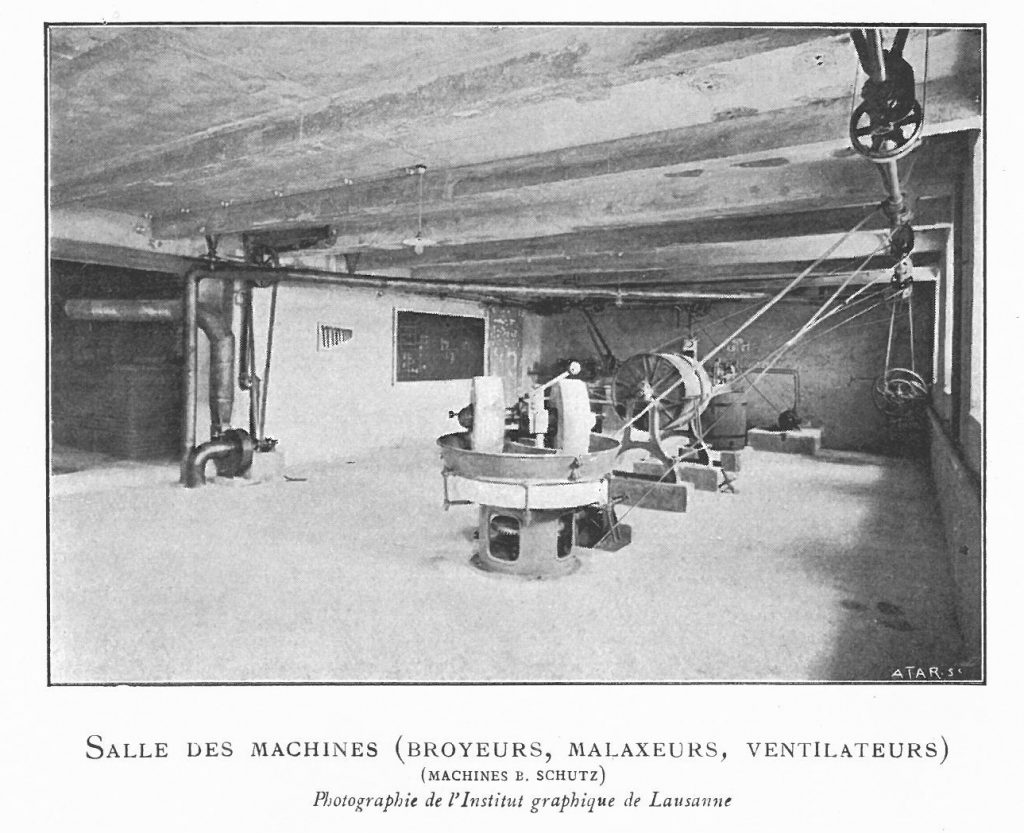

The Nouvelliste vaudois dated 2nd September (p. 2-3) contained a detailed description of the institution: “The machines are located in the basement: mills, extruders driven by electric motors, and kilns constructed by the engineer M. Bigot and fitted with a new system [probably Alexandre Bigot (1862–1927), a well-known French ceramicist who also had a PhD in physics]. The ground floor contains rooms for moulding, shaping and throwing clay, a chemistry laboratory and a changing room; on the first floor are the director’s office, the library and the exhibition room, rooms for drawing, painting and for the final assignments and another two rooms for theory classes; the director’s apartment is on the top floor.”

Source: Savreux 1914

The only publication about the Swiss School of Ceramics that we are aware of is a brochure written by Savreux and published in Geneva in 1914. The first part provides an overview of Swiss pottery from prehistory to the present. The second part contains the school regulations, a description of the machines provided, the course curriculum and a series of photographs of the technical facilities and different class rooms (Savreux 1914 – for more information on the building itself see also Lüthi 2017, 134 and Fig. 11).

Source: Savreux 1914

The regulations stated that the aim of the school was to “train ceramic workers and foremen”. The duration of the apprenticeship was set at four years and the minimum age at 15, although “young people who are deemed proficient can leave the school after three years with an apprentice’s certificate”. Graduates of the complete four-year course were awarded a “ceramicist’s diploma”. Students from abroad whose parents were not resident in Switzerland were charged annual fees of 100 Swiss francs, while Swiss students paid 50 francs per year.

The curriculum was rather ambitious: workshop skills included the making of plaster models and moulds, throwing, shaping,m casting and trimming (stoneware, refined white earthenware, porcelain). As well as a general education in French, arithmetic, elementary geometry, bookkeeping, history and social studies, the apprentices were also introduced to the basics of geology, mineralogy, physics (thermodynamics, expansion, calorimetry, hygrometry, the statics of liquids and gasses, optics, electricity), chemistry and ceramic technology (the properties of clay, dyeing methods, glaze research, firing techniques). There were also courses in the history of art and pottery, in technical drawing and in ornamental drawing.

The technical equipment included several potters’ and muffle kilns, kick-wheels and mechanical potters’ wheels, jiggers, a hydraulic press for the production of stove tiles, airbrushes and compressors, machines required for preparing the raw material (a mechanical blunger, a filter press, an Alsing ball mill, a horizontal extruder, mills for grinding coloured glazes) and a chemistry laboratory.

With regard to the teaching staff, the board of directors had advised the Council of State to appoint Frenchman Auguste Lasseur as preparer, model maker and machine fitter; Louis Pelet (1869–1941), Professor at the University of Lausanne, as Professor of theoretical and practical chemistry; Auguste Veuillet (probably a potter from Savoy) as master potter, François Zooler as master of “bacolage” (?) and as expert for slips and firing. The first courses were offered in September 1912.

On 29th January 1913 Ménétrey and Savreux were invited by the Société industrielle et commerciale de Lausanne to give a presentation on the school. According to a report on the presentation, early indications were encouraging as eight students had enrolled at the time. “One of their aims was to create a style that was unapologetically unique to our country, and which would enjoy the same esteem as the wares produced by certain Swiss factories that represent a very pure and original style of art” (Feuilles d’avis de Lausanne dated 1st February 1913, p. 12). In his presentation, the director exhibited a well-intentioned realism: “[…] students can rest assured that they will find work in their own country. The school does not intend to turn them into artists, but craftsmen whose skills have been honed by their observation of nature and their study of ceramic art from the best epochs” (La Revue dated 30th January 1913, 3).

For Lucien Ménétrey this meant that his dream had been fulfilled. He had created a perfectly equipped, modern school of ceramics which was managed by an outstanding expert in the field and which aimed to train qualified ceramicists who were proficient in all aspects of their craft and all areas of ceramic technique. As the first ever institution of its kind to be set up in Switzerland, the School of Ceramics definitely lived up to its name, though it was in no way benefitting from the kind of political, financial or administrative support a truly national institution should have enjoyed. Ménétrey’s visionary project had no choice but to meet the challenges posed by its economic independence head-on. It was a task that would jeopardise its continued existence more than once.

1913: the school produces and fires its first vessels

A shareholders’ meeting on 16th June 1913 was told of the smooth running of the school, which had 15 enrolled students, some of whose “works and remarkable fired pieces” (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 19th June 1913, 3) were available for inspection. The pieces presented on this occasion had probably resulted from a test run; the official first firing took place two months later, as can be seen below.

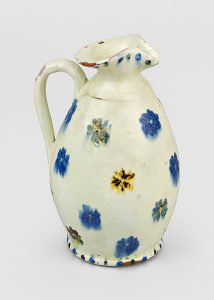

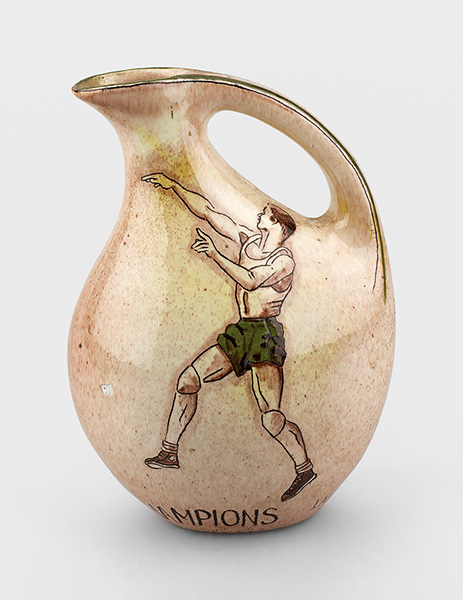

The collection of the Centre d’enseignement professionnel de Vevey (Vevey Vocational Centre) (CEPV) does in fact include a faience vase with a lead-tin glaze decorated with a floral frieze (by in-glaze painting) in blue, ochre and lilac. The pattern also contains the words “Swiss School of Ceramics – first firing – 1913” (CEPV G 15). This example is probably similar to two flower vases that were donated to the Grand Council of Vaud in August 1913 as “the first products of the school, which were put on display in the smoking room” (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 27th August 1913, 2). The Revue from that same Wednesday, 27th August reports on the vases that they were “taken from the potter’s kiln on Monday” (p. 3), which would make 25th August 1913 the date of the first official firing. This means that as well as the more common slipped earthenware the school was also producing faience from the very beginning; its instructors were clearly familiar with this technique and knew how to work with the lead-tin glazes required.

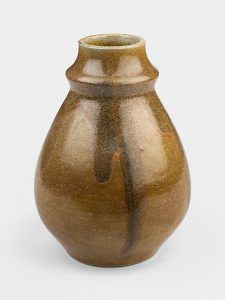

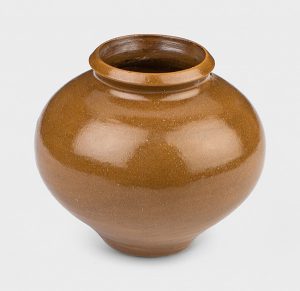

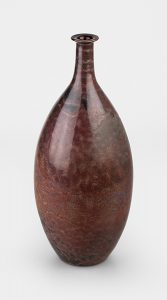

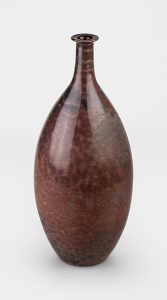

What is even more remarkable is that Maurice Savreux even managed to produce stoneware which was fired at very high temperatures; these were the first such vessels ever made in Switzerland (with the exception of the pieces that the French ceramicist Paul Beyer is said to have made in 1906/07 at Pasquier-Castella’s pottery workshop in Renens – see the chapter «Renens et Chavannes-près-Renens – Les poteries»). The CEPV has a few examples – with the relevant date – of this historically important stoneware in its collection (CEPV 5.B.2; CEPV No. 6; CEPV No. 5; CEPV Nr. 4; CEPV No. 7).

Various advertisements announcing the beginning of the school year also mentioned porcelain making as one of the techniques on the curriculum. While we are not aware of any surviving examples, the school does seem to have sent some students’ works from this course to be put on display at the 1914 National Exhibition in Bern (La Revue dated 9th May 1914, 1-2). Were these porcelain objects produced entirely in Chavannes or were they only decorated there? The question remains unanswered for the time being.

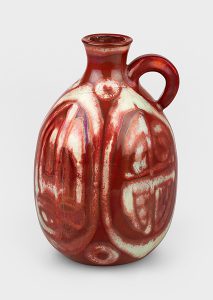

In its report on the 1914 National Exhibition, the Gazette de Lausanne paid homage to “the new ascent of pottery making, an art form with a splendid past that had become weighed down by tradition”. The new School of Ceramics in Chavannes-Renens played an important role in this ‘Renaissance’. The reporter was particularly keen on the variety of pieces that were presented by the school, “ranging from outstanding stoneware to the finest porcelain”. He had particular praise for the pieces that were decorated using a process devised by a Mr Bonifas from Geneva, “which involved adding fragments of gold and silver leaf to enamel to great artistic effect” (issue dated 23rd July 1914, 3). Paul Bonifas attended the school between 1913 and 1914, where he became familiar with the technique of making stoneware, which he would use a short time later, between 1915 and 1917, in his workshop in Versoix (Ariana 1997, 12).

For early examples of stoneware pieces made by Bonifas see: mudac 1001; mudac 1000; MAHN AA 2238; MAHN AA 2241; MAHN AA 2242; MAHN AA 2243; MAHN AA 2244; MEAA 0319-2.

1914: the first crisis and temporary school closure

In the spring of 1914, some members of the Grand Council of Vaud led by Alfred Panchaud filed a motion to apply for state funding for the institution. The accounts for the construction of the building did, in fact, include a shortfall of 20,000 Swiss francs, so that the School of Ceramics was actually faced with the possibility of becoming bankrupt! Charles Burnier, the rapporteur of the committee that was tasked with reviewing the dossier wrote: “The Swiss School of Ceramics was founded as a public limited company. This was the first mistake: the law stipulates that schools of this type must be established by municipalities or local authority associations. […] The second mistake was that the school’s share capital was far too low. In any case, it was in no way adequate given the size of the building that was constructed, its technical equipment and the tuition being offered there today. With a capital of only 5,000 francs, one should never have contemplated setting up a school that is so complete that it could almost be termed a model school compared to what we are currently being asked to support. The third mistake was to attempt to set up a vocational school that did not answer any immediate or urgent needs. This is a very good example of the danger that one exposes oneself to when following a dream – albeit a sublime and generous one – without enquiring in any great detail about the feasibility of the endeavour […]” (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 13th May 1914, 1). In plain terms: Ménétrey’s project was far too ambitious, and the approach taken to getting it up and running was exceptionally reckless, particularly when it came to securing funding. It does appear, however, that the main driving force had been aware from the very beginning of the financial difficulties that would hamper the development of his school. Did he perhaps know that the state would not be able to turn back the clock once the wheels had been set in motion?

Because the commission chaired by Burnier ultimately concluded that, in light of the good results achieved by Savreux, the school “will advance our industry and may allow us to keep up with our competitors from abroad”, it submitted the motion filed by Panchaud and others to the Council of State, with the urgent recommendation to take any measures necessary to save the school from becoming bankrupt and to secure its continued existence, although it was clear that the executive had already excluded the possibility of finding the necessary funds in the construction accounts. In his statement, the rapporteur pointed out that “everyone knows that the Swiss School of Ceramics was established primarily upon the initiative of a private citizen, who may have made an error of judgement but who has sacrificed everything for this project, which he himself has paid for and has worked very hard to bring to fruition, [… and] that one must admit that others were as misguided as he was” (Nouvelliste vaudois dated 13th May 1914, 1 – the piece in the journal is almost a verbatim copy of the official report from the committee, which was published in the Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil [Sessions of the Grand Council], spring 1914, 137-143).

At a meeting of the Grand Council on 11th November 1914, Mr Laffely, Mayor of Morges and member of the schools committee, put the question to the government as to the measures they were planning on introducing in answer to the motion filed by Panchaud and others. State Councillor Chuard reminded those present that the institution in question had been founded a little hastily and without any consideration for securing the funding required, and that the federal and cantonal governments had agreed to fund a third of the annual expenditure each, which amounted to 25,000 francs in total. “The school can only hope to have its finances managed properly if it becomes a municipal institution as required by law. The municipalities in question, however, can only contribute a maximum of 2000 francs. As a consequence, it is impossible to come to a decision, given that the Federal Department of Trade and Industry has announced its intention to reduce its subsidies.” After a rather lively exchange between the different speakers, the Council of State concluded that the school would be able to continue to operate thanks to the subsidies, and that it was only the real estate company that owned the building that was under threat. Chuard eventually promised that negotiations would continue (Tribune de Lausanne dated 12th November, p. 3).

In the meantime, war had broken out in Europe. Because the main instructors at the school – and most importantly its principal – had been called up to fight in France, the school was forced to close its doors in the autumn of 1914. The cantonal authorities subsequently outlined the school’s future by promising more financial support, provided that the municipalities in the region came together to form an ad-hoc group which would grant a collective subsidy of 2000 francs per annum (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 8th December 1914, 3).

An article in the Gazette de Lausanne dated 3rd November 1914 (p. 4) reported that the war was causing serious operational problems for all local pottery producers, whose staff mainly consisted of French or German citizens who had also been called up. “Had the School of Ceramics been established two years earlier, these factories would now know where to recruit their staff – namely in Switzerland, and that would have been no harm”.

1916: a new beginning

As early as April 1916, the Department of Public Education ran advertisements announcing the reopening of a “reorganised” school in May (La Revue dated 6th April 1916, 4). It was at the department’s suggestion that the limited company leased the building to the municipality of Chavannes at the time (Feuilles d’avis de Lausanne dated 28th March 1916, 15). The reopening eventually took place on 15th June and the celebrations were attended by the President of the school board, Henri Dusserre, Lucien Ménétrey’s son-in-law and director of the Poterie moderne (La Revue dated 16th June 1916, 3).

The bankruptcy of the school’s limited company was eventually published in the Swiss Official Gazette of Commerce on 15th December 1916 (SOGC, Vol. 35, 1917, 102), and the company name was struck off from the commercial register at the same time (SOGC, Vol. 35, 1917, 104). The Feuille d’avis de Lausanne reminded its readers that this only referred to the school’s real estate company, which owned the building, and did not apply to the school itself, which was managed by the municipality of Chavannes and supervised by the state (issue dated 2nd May 1918, 3). The real estate was put up for public auction by the bankruptcy office, and was bought by Lucien Ménétrey and Louis Laffely. Estimated to be worth more than 93,000 Swiss francs, they paid only 60,000 francs for it (La Revue dated 29th August 1917, 3). The new owners continued to lease the premises to the municipality of Chavannes-près-Renens, which was tasked with the school’s administration on behalf of the contributing communities in the locality.

The state-driven reorganisation of the school also had an impact on the curriculum, which was now “largely practical and aims to impart to students a body of knowledge that is as sound as anything that can be learned in an apprenticeship, only more complete, more coordinated and more methodical” (Tribune de Lausanne dated 6th May 1916, 4). The difference between this and what Savreux had in mind originally is not obvious; we can, however, assume that the “artistic” and scientific components of the curriculum were considerably reduced and that the more challenging skills such as stoneware or porcelain production were put to one side for the time being. An explanatory statement which accompanied the 1919 draft law on vocational education makes reference to the thought processes of the authorities at the time: “As early as 1915, a number of municipalities got together under state leadership to work on reopening the school. The municipality of Chavannes was tasked with its administration. The school had previously focused on training ceramic artists, and had a specialist director and several instructors. It has now been reorganised on a more cost-effective basis and with the immediate aim of training skilled potters first and foremost. The first group of 10 students graduated from the school in 1918 after a two-year course” (in: Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil. Ordentliche Herbstsession 1921,988). The duration of the course had therefore been shortened to two years, at least for the time being; it was once again extended to three years in 1923, and from then on, students were provided with a statutory apprenticeship contract according to the new law on vocational education.

The management of the school – which by contrast to Savreux’s previous function was now identified as “administrative” – was entrusted to Justin Magnenat, teacher, secretary and at the time president of the town council of Renens. A few days before the school reopened, the Council of State had appointed Jean Johannel as technical instructor and Nora Gross as arts teacher (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 10th June 1916, 23). Johannel (died in 1935), had settled in Ferney-Voltaire in 1907 and had made his name as one of the most innovative potters in the area, though he was not very successful in matters of business; in 1918, two years after taking up his post at the School of Ceramics, where he continued to teach until 1921, he was forced to sell his pottery workshop (Clément 2000, 93-94).

The CEPV (Vevey Vocational Centre) is home to a slipped earthenware vase that is reminiscent of works made between 1903 and 1905 at Bendicht Loder-Walder’s workshop in Heimberg to designs by Nora Gross (CEPV G 22). In the absence of a maker’s mark, it is difficult to say whether this vase was made by Nora Gross herself or by one of her students. We have also not yet been able to ascertain how long Gross taught at the Swiss School of Ceramics. What we do know, however, is that she continued to maintain close contact with the school in the subsequent years. In 1922, she exhibited some of her ceramic objects as part of the 1ère Exposition nationale d’art appliqué (1st National Exhibition of Applied Art) which was staged by L’Œuvre in Lausanne. It was an important event, behind which Gross was one of the main driving forces. Because of the contacts that Gross had made with the management of the school, Daniela Ball believes that the exhibits were created at the school’s workshops (Ball 1988, 125). The Musée Ariana has in its collection a bonbonnière that was acquired during the 1922 exhibition (MAG C 0797 – Ball 1988, Cat. No. 28), as well as a lidded vessel which was ordered at the same time but not delivered until the following year (MAG C 0800 – Ball 1988, Cat. No. 29). Both specimens bear the impressed mark “Nora Gross” and a model number.

The Historical Museum in Lausanne has another bonbonnière of this type in its collections that bears the same impressed mark as the bonbonnière at the Musée Ariana (MHL No. 12).

The old collections of the Swiss School of Ceramics that are housed at the CEPV include a number of carefully made slipped earthenware pieces with stylised geometric or vegetal patterns which may have come from some of Nora Gross’s classes (CEPV G 3; CEPV G 2); two objects are even signed: “A. Graf” (CEPV 5.D.2) and “C. Yung” (CEPV G 4). We would like to stress that associating these objects with Nora Gross’s teaching remains purely speculative for the time being because it has not been possible to date them with any degree of certainty.

The teaching staff appears to have increased somewhat in the 1920s. The annual reports mainly mention Louis Martin, J. Lambercy, Louis Barbay, Gustave Mayor (potter), Jean Tschanz, Henri Terribilini (registered as technical instructor in 1922/23), although not all taught at the school continuously.

In 1922 the Council of State appointed Ernest Becker (1883–1978) as the new director of the school (La Revue dated 23rd February 1922, 2; Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 5th May 1949, 2). Born in Brussels to parents who were naturalised citizens of Martherenges in the Canton of Vaud, Becker studied fine arts in Nancy and Paris before settling in Lausanne where he became a landscape artist; in 1911 he was employed as an arts teacher at primary school level (Tribune de Lausanne dated 11th November 1911, 2).

A vase of questionable aesthetic quality in the school’s collection bears a label written by Becker where he clearly distanced himself from the work of his most recent predecessors: “Pottery of the kind that was being produced at the school when I took over as director in 1921” (CEPV G 20).

The same collection also contains a few earthenware vessels in a similarly rustic style (CEPV G 14; CEPV G 18), including one of only a few dated specimens – a vase from 1919 (CEPV No. 10).

The Historical Museum in Lausanne houses two commemorative plates from 1924 with a decoration that was inspired by one of Ernest Becker’s drawings (MHL AA.46.B.55).

By appointing a director with an arts degree the authorities were probably trying to realign the school’s orientation and more importantly rectify a certain decline in the quality. The institution had also clearly regressed in technical terms, even to the extent of losing its autonomy, as we can see from this passage in a 1923 report of the sub-committee of vocational schools: “thanks to the proximity of the Poterie moderne and the goodwill of its director [Henri Dusserre], the vessels can be fired using the factory’s kilns. […] The state should intervene and should not rely too much on the initiative of the municipal authorities of Chavannes. The school does indeed appear more like a cantonal school than one that is managed by a municipality. Despite the limited means that are available to it and the equipment that leaves much to be desired, it is currently fulfilling the purpose it was created for” (Report by the sub-committee of vocational schools, in: Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, extraordinary session April 1923, 268).

1925: the cantonal authorities take over the running of the school

The wishes of the committee members were heard and in November 1925, the Council of State granted a credit of 125,000 Swiss francs “to purchase the buildings that are currently being used by the Swiss School of Ceramics in Chavannes-Renens, and for maintenance work to be carried out on the school’s kilns” (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, ordinary autumn session 1925, 95). When Louis Laffely died on 14th April 1925 (Tribune de Lausanne dated 16th April 1925, 2) Lucien Ménétrey was forced to put the building and all its contents up for sale. The decision of the cantonal legislative was prefaced by a detailed statement written by Amédée Milliquet, the rapporteur for the relevant committee, who traced the entire back history of the dossier (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, ordinary autumn session 1925, 90-95). It tells us, that the increase in the number of students in 1924 to 24 had allowed the school to “hire qualified teaching staff from the porcelain [sic] and pottery factory in Langenthal as well as a former graduate of the national School of Ceramics in Sèvres” (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, ordinary autumn session 1925, 93 – Statement of grounds and draft decree, ibid., 497-504). This referred to Jean Lorenz, master potter and former foreman at the Langenthal manufactory, and Albert Blémond, who according to the directories, held the position of production manager until 1926/27. He taught shaping, moulding, decorating, firing, chemistry and technology! An Albert Blémond also taught technical drawing at the school in Sèvres from 1945 to 1967 (list of personnel in Sèvres, at http://www.thefrenchporcelainsociety.com).

Since it was now under the sole control of the state, the school was able to look to the future with a certain degree of calm. The fact that Becker remained in charge of the school for many years – he held the position until 1949 (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 5th May 1949, 2) – was another source of stability.

From 3rd September to 9th October 1927, the school took part in an exhibition dedicated to Swiss pottery staged by the Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève (Geneva Art and History Museum) and submitted a relatively small group of six objects: two stoneware vases, three earthenware vases (one bearing underglaze brushwork decoration, two with a poured slip decoration) and an incense burner decorated with colourful slips (Geneva 1927, 23, No. 277-282). In a rather blunt critique on the exhibition, Lucienne Florentin, the infamous art critic from Geneva, wrote: “It [the Swiss School of Ceramics] is exhibiting two beautiful stoneware vases – but they were made 14 years ago and already appeared at the Bern exhibition in 1914 … The other vases, ordinary pottery, are completely uninteresting” (L’Œuvre 14, 1927, 286). The school had apparently settled for “recycling” the stoneware vases that had been made in 1913.

In the spring of 1927, the school exhibited some of its students’ works within its own classrooms. The Lausanne media were considerably more enthusiastic: “We are surprised by the diversity and quality of the works these young people have produced. The porcelain, faience and ceramic wares attest to their discerning taste; nature and the imagination of these young people are important sources of inspiration for their motifs. Naturally, the genres that have stood the test of time and continue to do so, such as the works from Sèvres and Saxe, and the old Swiss schools have not been neglected. […] The school produces anything one could possibly think of in the area of pottery making and ceramics, ranging from the milk jug and tureen to the most elegant table service and the most charming amphorae, from the ashtray to the bonbonnière etc. Here are some plates and vases that have been prepared for the next Fête des vignerons (winemaking festival) (see the chapter «Renens et Chavannes-près-Renens – Les poteries») (La Revue dated 16th April 1927, 2).

From 1928 onwards, students were given a choice of three subjects to specialise in: throwing, mould making and plaster of Paris casting, and pottery decorating (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 4th April 1931, 24). A former student, Paul Gerber, became one of the technical instructors, teaching at the school from 1928 to 1930/31. The well-known Heimberg potter Cäsar Adolf Schmalz (1887–1966) taught in Chavannes in 1931 and 1932 (see also Marti/Straubhaar 2017). Two technical instructors newly appointed in January 1936, Jean Allenbach and Claude Vittel, would have a lasting impact on the teaching in Chavannes and later in Vevey (Tribune de Lausanne, 23rd January 1936, 4). Jean Allenbach (1910–1978) had attended the Swiss School of Ceramics himself in the 1920s and later led the department of pottery at Vevey until his retirement in 1975 (24 Heures dated 10th October 1975, 19). Claude Vittel (1907-1993), who was also a former student in Chavannes, had also studied in Koblenz and Bunzlau in Germany. He specialised in pottery technology and wrote a reference work published in 1976: Pâtes et glaçures céramiques.

In 1938, the Swiss School of Ceramics marked its 25th anniversary by staging an exhibition of students’ works on the premises of the company Steiger in Lausanne at rue Saint-François. The author of the report in the Feuille d’avis was none other than the Lausanne ceramicist Pierre Wintsch. He mainly spoke about the “technical perfection” of the exhibits and noted a distinct improvement compared to the objects that had been on show two years earlier: “[…] improvements are manifest in the more elegant shapes, in the choice of glazes in more nuanced shades and in the tastefully decorated pieces. […] A few beautiful vases are particularly worth mentioning, as are simple apple cider jugs with enamel decorations in matt blue-grey, beige or metallic black, which could easily hold their own in comparison to the works of well-known potters” (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 14th September 1938, 4 – for a slightly longer and signed version see Le Droit du peuple dated 21st September 1938, 4). A somewhat more nuanced report on the exhibition, written by somebody called “Jacques” can be found in Le Droit du peuple dated 23rd September (p. 4): “[…] all techniques are being used, including moulded decoration in relief on the plates. No effort was spared to make the vases, saucers and ashtrays as beautiful as possible. The colours are gorgeous and highly varied. There is a wealth of decoration, two or three on one vessel, some in a great many colours. The decorative motifs are well thought through, though sometimes a little too ordinary. I would direct the same criticism at the works overall. They are not completely convincing. It is this element of mastery that is lacking everywhere, except perhaps in one large vase that is on display separately in a showcase and is a credit to the potter who made it. One should not expect too much of beginners but this is the standard they should aspire to. Most of them are confident and sure of their work, and some are even virtuosos. All the more reason for them to try to improve on the aesthetics of their vases. Since the last exhibition staged by the school, a rich range of colours has been added to the repertoire, particularly a very trendy turquoise blue that is gloriously fresh looking.”

This Information booklet on Swiss ceramicists probably came out on the occasion of the 1938 anniversary event.

A printed school curriculum from the period between 1945 and 1947 describes the course in detail.

detail.

In 1949, Pierre Wintsch put pen to paper again to write about a new exhibition put on by the students from the school in Chavannes. His article clearly shows the variety of techniques that were being taught at the school: “Let us first mention the pottery whose matt-blue glaze is incised to reveal the beauty of a decoration made darker by the rougher material. The exhibition includes another series of pottery with sgraffito decoration which revisits the old techniques used by the potters of Thun but endows them with a new spirit: incised decoration covered in two coats of slip, one black, the other off-white, and then highlighted by adding fresh colours under a transparent glaze. Other exhibits include faience vessels with floral designs of fields and forests, while other objects have lustre glazes, some of which are beautifully decorated in the tradition of old Chinese stoneware. And to round off this small review some beautiful semi-vitrified vases with a striking decoration consisting of black linear patterns” (Le Peuple dated 16th September 1949, 5).

In the year before the exhibition, the school had been invited by the Musée d’art industriel et d’art décoratif (Museum of Industrial and Decorative Art) in Lausanne to co-curate a didactic exhibition of pottery which was set to run from 15th November 1948 to 15th February 1949 at the Palais de Rumine. The displays included a didactic presentation of the different techniques – earthenware, faience, stoneware and porcelain – which was devised in collaboration with the school, and an historical section supported by loans from various antiques dealers, collectors, museums, manufacturers and artists (La Nouvelle revue de Lausanne dated 23rd November 1948, 3 – Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 19th January 1949, 44).

The school itself donated a small group of students’ works which gave an impression of the types of object that were being created at the time: MHL AA.MI.1876; MHL AA.MI.1877; MHL AA.MI.1878; MHL AA.MI.1880; MHL AA.MI.1894.

All examples shown were made using a faience-type lead-tin-glaze which was suitable for creating all kinds of visual effects ranging from a shiny black glaze like the one used by Paul Bonifas (MHL AA.MI.1874) to the sober effect of a white glaze that is more likely to emphasise a complex formal quest and is reminiscent of certain works created by Noverraz in Geneva (MHL AA.MI.1876). The same technique is also suitable for creating polychrome decoration (MHL AA.MI.1877; MHL AA.MI.1878). The old slipped earthenware technique had not been forgotten, however, as demonstrated by an armorial dish at the Museum of Old Baulmes (MVB 1106).

The annual report by the Council of State’s sub-committee for vocational schools for 1948 includes a brief overview of the school’s activities: “The current director has trained 260 students over the past 27 years, 50 of whom later occupied managerial positions in companies throughout the German-speaking part of Switzerland” (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, spring 1948, 841). Female students were accepted at the school from the beginning of the school year of 1951 but only in the decoration department.

1950-1956: a new crisis leads to the pottery course being integrated in the Vevey School of Arts and Crafts

In 1950, all cantonal vocational schools were put under the remit of the Department of Trade and Industry. Under the chairmanship of State Councillor Paul Chaudet, the new supervisory authority deemed it necessary to reassess the School of Ceramics to ensure “that it meets the requirements of the craft and industrial enterprises concerned”. A commission set up for the purpose initially suggested taking the school out of isolation and incorporating it into the Vevey School of Arts and Crafts (L’école des arts et métiers), for which the municipality of Vevey was planning to construct a new building. This idea identified the existence of potential synergies with regard to both the premises and the teaching staff (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, spring 1952, 1143).

In 1950, Pierre Wintsch put pen to paper once more to write about another exhibition of students’ works hosted again by the company Steiger in Lausanne. There are a few clues pointing to new trends that, as per the spirit of the time, were used in the workshops at Chavannes: “The shapes are simple, the decorations are usually freely crafted. Monochrome pieces are covered in various overlying coats of glaze in an attempt to create harmonious shades and to vary the intensity of the lustre or lack thereof: matt pastel blue, with incised decoration, black decoration under turquoise glaze, copper red due to firing in a reducing atmosphere etc.” (Le Peuple, 23rd September 1950, 5).

The collection of the CEPV includes a series of works that illustrate some of the decorative processes described above. They were used, always on refined white earthenware, until the 1960s, which is why we have found it difficult to precisely date the examples in question. The pieces shown here have several coats of glaze:

CEPV No 3; CEPV No 9; CEPV No 12; CEPV No 15; CEPV No 18; CEPV No 19; CEPV No 20; CEPV No 22; CEPV No 26; CEPV No 30; CEPV No 32; CEPV No 33.

Other examples exhibit the famous copper red which was becoming more and more popular and was achieved by firing the pieces in a reducing atmosphere: CEPV G 33; CEPV No 23; CEPV No 13; CEPV No 14; CEPV No 29; CEPV No 28; CEPV No 1; CEPV No 27; CEPV No 25; CEPV No 24; CEPV No 2; CEPV No 35.

Alongside these innovations, the school further refined the technique of producing slipped earthenware, particularly for its range of commemorative objects which were an occasional source of revenue for the institution (MHL AA.VL 2008 C 6683).

In early 1951, the Council of State appointed a new director, initially on a temporary two-year contract. René Burkhardt was resident in Mozzate (Italy) at the time and would eventually stay on in the role until 1956 (Avis de Lausanne dated 30th January 1951, 13). To mark its 40th anniversary, the Swiss School of Ceramics again staged an important exhibition in collaboration with the Museum of Decorative Arts in Lausanne entitled “Céramique suisse ancienne et contemporaine” (Old and contemporary pottery from Switzerland), which ran from 20th September to 16th November 1952 at the Palais de Rumine. In his opening speech, Burkhardt expressed his delight in “the happy renaissance of his school under the leadership of new technical instructors including [Jean-Jacques] Mennet and [Jean-Pierre] Kaiser” (La Nouvelle Revue de Lausanne dated 23rd September 1952, 2). Jean-Pierre Kaiser (1915–2001), was a painter, graphic designer and sculptor, and had been professor at the École cantonale de dessin et d’art appliqué (Cantonal School of Design and Applied Arts) in Lausanne since 1950. Jean-Jacques Mennet (1889–1969) was a painter and graphic designer and taught at the canton’s school of arts from 1920 to 1955. Advertisements promoting the Swiss School of Ceramics, particularly in the l’Éducateur et Bulletin corporatif (e.g. in volume 88/1 dated 12th January 1952, 1), describe Mennet as being responsible for its “artistic direction” until 1956. The same advertisements also list a new course: “Preparatory course for industry executives”.

The “old” part of the 1952 exhibition appears to be limited to a retrospective of slipped earthenware from Heimberg, which was part of the museum’s collection. The contemporary pottery formed the core of the exhibition and consisted of some 600 works by 70 artists from all over Switzerland, including the schools at Chavannes-près-Renens, Bern and Geneva as well as the pottery department of the Cantonal School of Design and Applied Arts in Lausanne. Another retrospective was devoted to the famous ceramicist Paul Bonifas, a former student at Chavannes. It consisted of four works that were shipped especially for the occasion from Seattle, where the artist had settled after the end of the Second World War (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 23rd September 1952, 2 – Tribune de Lausanne dated 25th September, 5 – La Nouvelle Revue de Lausanne dated 23rd September, – L’Illustré dated 23rd October, 19).

The future of the school was in jeopardy, and its imminent closure became a reality when the Council of State, at a meeting on 16th September 1955, made the decision to close the Swiss School of Ceramics “as soon as possible”. The news caused significant disquiet among the people of the region and those affected by it, which prompted a group of delegates led by Eugène Kuttel to submit an interpellation demanding an explanation. In its reply the executive reiterated its opinion that the school was only partially fulfilling the requirements of trade and industry. The commission that had been set up in 1950 to examine the possibility of reorganising the school had come to the conclusion that “if there was not already a school of ceramics, it would be hard to justify opening one. While at the time (in 1950) it also did not seem justified to contemplate a sudden cessation of its activities, it was decided that the school should be provided with the necessary means to achieve higher and more comprehensive goals. […] the institution at Chavannes was to become a centre of research and information which would be beneficial to all sectors of the Swiss pottery industry, and which would therefore accommodate the efforts of the practicians.” An estimate of the costs involved in redesigning the facilities was being prepared, when a proposal was made by the authorities to incorporate the school into the Vevey School of Arts and Crafts. In the initial phase, which began on 1st July 1953, the school at Chavannes was brought under the administration of the school at Vevey, while the students were still taught at Chavannes and the school’s activities continued to be funded by the state. This gave the municipal authorities of Vevey enough time to decide whether or not to take over the School of Ceramics and turn it into a new department of their School of Arts and Crafts. They seemed to be interested in doing so, provided they would not have to bear the costs of running the department in question. During the debate, State Councillor Oulevay expressed his “[…] regret that students graduating from this school after a three-year course […] are not able to make a living from their craft. He reminds us that a pottery student costs 4825 francs while an apprentice mechanic costs 1700 francs” (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, autumn session 1955, 830-840).

In August 1956 the Grand Council was told that “thanks to an agreement made with the municipal authorities of Vevey, the Council of State was able to reverse its decision taken on 14th September 1955 to close the Swiss School of Ceramics”. The school would therefore become a department of the Municipal School of Arts and Crafts in Vevey and continue its activities (minus the casting and moulding departments) there. The premises in Chavannes would continue to be occupied by the pottery department until the planned new building in Vevey was complete, while the building in Chavannes was still owned by the state and managed and supervised by the municipality of Vevey (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, spring 1956, 640-641).

On 1st April 1956, the School of Ceramics was, in fact, brought under the administrative and financial control of the municipality of Vevey (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, spring 1983, 478).

In the spring of 1958, the school staged its first exhibition of students’ works in five years in the Galerie du Capitole in Lausanne. Thanks to a report by L. Bovey (article in the Tribune de Lausanne dated 27th March (p. 3) the event took on a special significance “as an epilogue, or better still, as the culmination of a madcap adventure. The Swiss School of Ceramics had, in fact, been about to close its doors when pottery began to experience an upswing”. When looking at the works on display, which the journalist described as being “remarkable in every way”, he expressed his delight about the school’s survival by becoming a department of the Vevey School of Arts and Crafts. He particularly mentioned “a beautifully modelled vessel with a red lustre; a slender smoky red vase; a stoneware vase in Chinese red; a matt grey cup with abstract decoration”.

As a side note it is worth mentioning that from the 1950s onwards the school had once again begun to produce stoneware (CEPV No. 8; CEPV No. 11; CEPV No. 17; CEPV No. 21; CEPV No. 34). Writing about the same exhibition, Jean Charpié in Pour Tous (issue dated 1st April 1958, 23) pointed out that graduates from the school “could seek employment from industrial enterprises, particularly those in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, or set up their own workshops. The latter option appears to be the most interesting, as pottery is used increasingly more often to decorate public buildings, schools, factories and other public facilities, not to mention all the decorative earthenware objects that are common in modern interior design. […] In the exhibition we had the pleasure of seeing some of the works created by former students who have since achieved fame, including Bonifas, Wintsch, Lambercy, Gasser, Chapallaz and others. These names show that being a ceramicist, and being a self-employed ceramicist, can provide deep satisfaction”.

As the industry stagnated (particularly in the French-speaking part of Switzerland), the decorative arts experienced a massive upturn and the studio potter concept of the English-speaking world gained traction, the standing of ceramicists improved considerably. Thanks to this development, the school’s existence was more justified than ever, and in 1959 it counted no fewer than 45 students (Feuille d’avis de Lausanne dated 10th August 1959, 7).

In 1964, the Grand Council enacted a decree which authorised the executive to subsidise 30% of the running costs of the future Vevey Vocational Centre. The specifications for the building included the incorporation of the Swiss School of Ceramics. The running costs of the Chavannes school, on the other hand, would be borne exclusively by the municipality of Vevey (Bulletin des séances du Grand Conseil, autumn 1963, 1242-1253).

The new Vocational Centre, the Centre Doret, was built between 1967 and 1971 and the School of Ceramics moved to Vevey in the summer of 1970, at which point the name “Swiss School of Ceramics” was dropped for good and the school was simply known as the Pottery Department of the CEPV (Centre d’enseignement professionnel de Vevey). As an institution, the CEPV asserted itself as one of the main educational establishments in the country with regard to the discipline of pottery making and maintains a leading position to this day.

In 1970, the municipality of Chavannes-près-Renens bought the former school premises at 46 Avenue de la Gare and turned it into its townhall, a function which it still serves today.

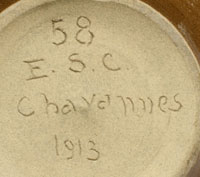

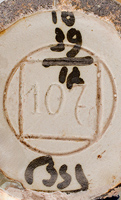

Makers’ marks

Besides incised marks consisting of the initials “E. S. C” that can be found alongside the name of the place of manufacture on a few stoneware objects from 1913, the school mainly used an impressed mark consisting of a Swiss crossbow and the initials “E. S. C.”. (MHL AA.MI.1876).

Because the crossbow symbol was introduced as the original Swiss mark by the Verband für Inlandsproduktion (Association for Domestic Production) in 1931 (SOGC, Volume 49, 1931, 1086 – Pastori-Zumbach 2001), this particular mark cannot date from before that. It continued to be used – albeit probably not in any systematic way – until the late 1940s (MVB 1106; CEPV No. 11). The students may have sometimes used personal marks, probably from as early as the 1950s, which we have not yet been able to decipher.

Many of the school’s products bear labels with the name of the school, initially without the crossbow symbol (CEPV G 2), and later with it (CEPV 5.D.2; CEPV No. 1; CEPV No. 14). These labels must have been used to identify the school’s pieces when they were put on display in the exhibitions.

Translation Sandy Haemmerle

Sources

Canton of Vaud press and annuals as well as the Grand Council bulletins, accessed via the Scriptorium database of the Cantonal and University Library in Lausanne.

Swiss journals, accessed via e-periodica.ch.

Siehe auch: https://notrehistoire.ch/galleries/ecole-suisse-de-ceramique-chavannes-pres-renens

See also: Exposition Conférences 2013 und CEPV-Actualites

References:

Ariana 1997

Paul Bonifas, céramiste du purisme. Catalogue d’exposition, Genève, Musée Ariana. Genève 1997.

Ball 1988

Daniela Ball, Nora Gross (1871-1929). Genava. Bulletin du Musée d’art et d’histoire de Genève XXXVI, 1988, 117-135.

Clément 2000

Alain Clément, La poterie de Ferney: deux siècles d’artisanat. Yens-sur-Morges/Saint-Gingolph 2000.

Genève 1927

Exposition de céramique suisse. Catalogue d’exposition, Musée d’art et d’histoire. Genève 1927.

Langlade 1938

Émile Langlade, Artistes de mon temps. Arras 1938.

Lüthi 2017

Dave Lüthi, Les écoles professionnelles en Suisse: palais ou usines ? In: Histoire de l’éducation 147, 2017, 119-146.

Marti/Straubhaar 2017

Erich Marti/Beat Straubhaar, C.A. Schmalz 1887-1966. Leben und Werk mit Pinsel, Stift und Lehm, Heimberg 2017.

Pastori-Zumbach 2001

Anne Pastori-Zumbach, Sous le signe de l’arbalète – La Marque suisse d’origine. Revue suisse d’art et d’archéologie 58, 217-228.

Savreux 1914

Maurice Savreux, L’art de la céramique en Suisse et l’École suisse de céramique. Genève 1914.